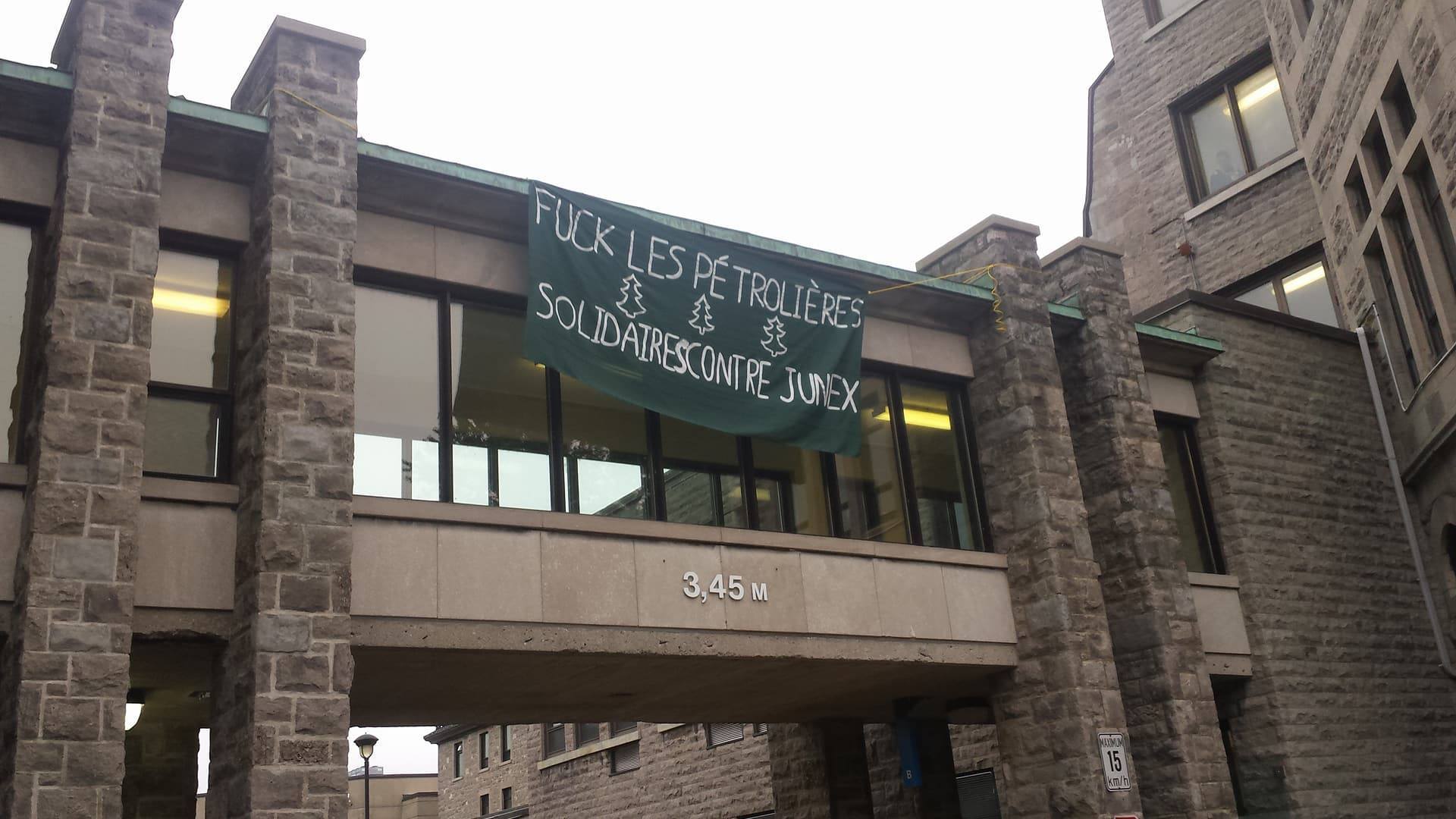

In the week of action in solidarity with the River Camp, a banner was dropped on the walkway of Cégep St-Laurent, reading “Fuck oil companies, solidarity against Junex”. Several students distributed fliers announcing a demonstration in solidarity with the River Camp. Due to positions and mandates against hydrocarbons, the AECSL (Student association of Cégep de Saint-Laurent) supports all initiatives that aim to struggle against oil companies. Solidarity!

Banner drop at the Resources ministery in Caplan, Gaspesie!!

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

Last night, after we climbed like ninjas on top of ministery buildings (with a view of the magnificent Baie-des chaleurs), we hung a banner on the MERN offices (ministery of energy and resources):

Fuck that Resources Quebec that invests loads of cash in oil companies, and fuck that Resources Quebec, and fuck that Quebec! Yooouhouuuu Junex, petrolia, IT’S OVER!

Arson of two luxury cars in St-Henri

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

Inspired by the riots in Hamburg, we burned two luxury cars outside of a condo in St-Henri during the night of July 13. In a neighbourhood where people have to choose between food and rent, don’t be surprised when we set fire to your flagrant displays of class privilege.

We used a simple method: fire sticks half-covered in fire-paste. All the material can be found in a camping store. We lit the fire-paste covered end and placed it in the top corners of the car’s grill, between the headlights. We used two sticks per car. The fire is mostly invisible until plastic or motor oil catches fire, giving you time to leave unseen. Be careful: the fire can easily spread to cars parked close-by.

The police who violently enforce gentrification had these encouraging words to say:

“[Montreal police Cmdr. Sylvain Parent] said police have increased their visibility in the neighbourhood in response to the attacks, but it’s hard to stop people who want to commit crimes. “If there’s someone who wants to do something and they see a police officer pass, they’ll wait until we pass by,” he said. “If they really want to do something, they’ll do it anyway.”

Until next time,

Black Masked Winners (BMW) / Anarchistes Uni.es Dans l’Insurrection (AUDI)

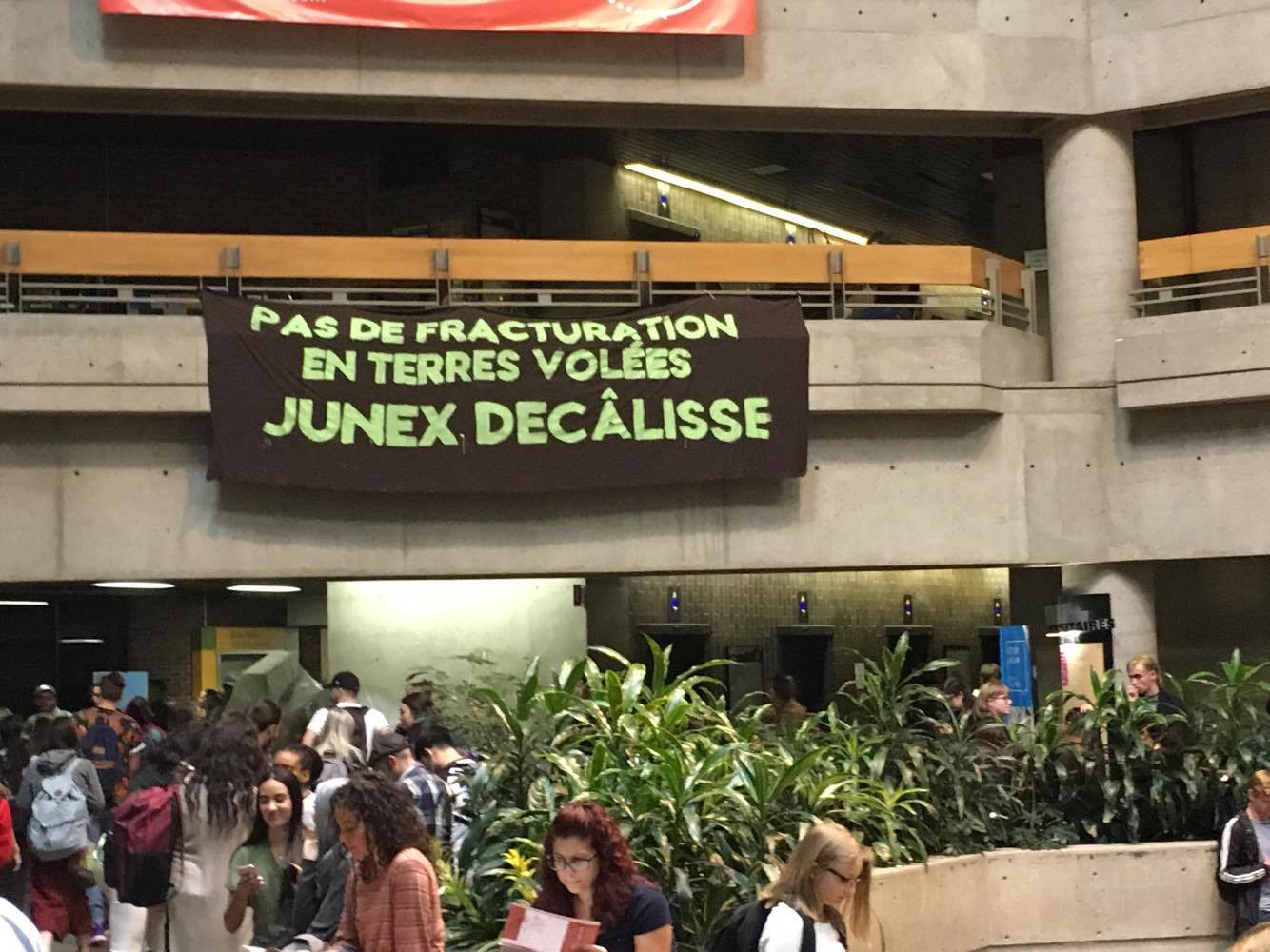

Banner drop: fuck off Junex

Banner drop: fuck off Junex

A banner drop and flyering at UQAM to kick off the week of action! We’re told that one of the militants encountered a family member of Lavoie, the family of the president and vice-president of Junex. We’re delighted to know that the message will be sent to them directly.

It wasn’t just McGregor who got beat last Saturday

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

Last week, a new racist group tried to publicly organize for the first time. Their name is Wolves of Odin[1. Editor’s note: From the Wolves of Odin facebook page – “FOUNDED IN THE WINTER OF 2016, WE ARE AN ORGANIZATION DEDICATED TO THE DEFENSE OF OUR CITIZENS AND WAY OF LIFE. ORIGINALLY ESTABLISHED AS A LOCAL GROUP OF CONCERNED CITIZENS HERE IN MONTREAL, OUR MEMBERSHIP HAS GROWN INTERNATIONALLY, WITH REQUESTS FOR SATELLITE GROUPS OUTSIDE CANADA. THE W.O.O. WAS ORIGINALLY FOUNDED IN RESPONSE TO THE GROWING IMMIGRATION CRISIS THAT IS BURNING OUT OF CONTROL IN MANY PARTS OF EUROPE. WE HERE AT W.O.O. UNDERSTAND THAT IN THE BEGINNING, IT WAS SEEN AS A NECESSITY TO AID OUR FELLOW HUMAN BEINGS THAT HAVE FLED THEIR WAR TORN COUNTRIES. MANY WERE WELCOMED AND PROVIDED FOR, YET MANY HAVE FORCED THEIR WAY IN UNDER THE GUISE OF REFUGEE STATUS, AND MANY MORE HAVE OVERWELMED THE UNDERSTAFFED BORDER CROSSINGS IN MANY COUNTRIES. CRIME RATES HAVE SKYROCKETED UNDER WAVES OF FOREIGN IMMIGRATION, AND THE FACE OF EUROPE HAS BEEN TRANSFORMED FOREVER. IN MANY PLACES OF EUROPE, IT HAS BECOME EXTREMELY UNSAFE FOR THE LOCAL, ORIGINAL INHABITANTS. REPORTS OF THEFTS, ASSAULTS, VANDALISM, RAPE, AND CHILD ABUSE, HAVE BEEN ACREDITED TO IMMIGRATION, IN WHAT WERE ONCE PEACEFUL COMMUNITIES, ATTEMPTING TO DO THEIR PART TO ALEVIATE HUMAN SUFFERING. WE REMAIN STEADFAST IN OUR BELIEF THAT THERE ARE MANY LEGITIMATE REFUGEES FLEEING THE ATROCITIES THAT THEY HAVE FACED IN THEIR OWN COUNTRIES, YET WITH THESE LEGITIMATE REFUGEES, COME MANY THAT WISH TO IMPOSE THEIR LAWS AND IDEOLOGY UPON US AS CANADIANS, AND OTHER CITIZENS OF GREAT COUNTRIES FROM AROUND THE WORLD. WE HAVE OUR OWN LAWS AND SOCIETIES. WE ARE PROUD OF OUR OWN RICH AND NOBLE HISTORIES. OUR ANCESTORS FOUGHT FOR OUR WAY OF LIFE, AND MANY GAVE THEIR LIVES SO THAT WE MAY LIVE FREE, SO THAT OUR FAMILIES AND FUTURE GENERATIONS MAY LIVE FREE. BY REFUSING TO YIELD, WE ARE ANSWERING THE CALL TO HELP KEEP THE LIGHT OF THE WEST BURNING BRIGHTLY. WE ARE THE WOLVES OF ODIN, AND WE WILL HOLD THE LINE”], not to be confused with Soldiers of Odin. They organized a small BBQ in a park in the west of the city. After eating and drinking, they decided to go watch the highly-anticipated boxing match.

Anti-fascists recognized them and came in large numbers to confront them. They then came outside to try to explain how they aren’t racist. Within five seconds, a beer bottle was shattered on one of their heads, and the others were taken care of. One of them ended up being stomped on the ground. Let’s say that they were bruised and bloodied, with three of them seriously hospitalized.

Even though these groups are still small, we want to completely prevent them from growing quickly. We await each of their initiatives with a capacity to strike.

Watch your backs fascists.

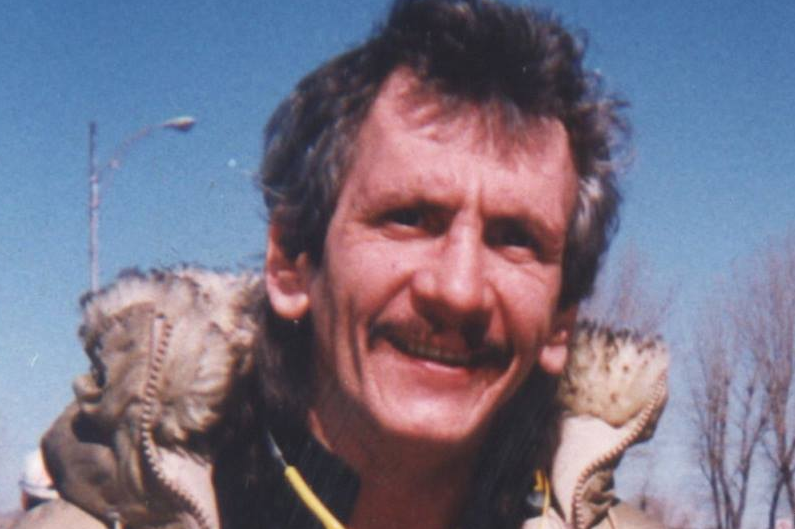

Justice and Jean-Pierre Lizotte, the Poet of Bordeaux Prison

On September 5, 1999, eighteen years ago, Jean-Pierre Lizotte died as a result of injuries sustained from the blows of a Montreal police officer. I’m re-sharing today an article that I wrote in 2008 (published, in a slightly different form, in the Montreal Gazette) about the “Poet of Bordeaux Prison”. RIP Jean-Pierre Lizotte!

The Gazette’s opinion pages recently provided space to the lawyer for Montreal police officer Giovanni Stante who was charged in the death of Jean-PierreLizotte in 1999. The lawyer takes offense to a Gazette report, subsequent to the police killing of Freddy Villaneuva in Montreal-Nord in August this year. He feels that the report gives the “false impression that Lizotte was a victim of police brutality.”

Stante’s lawyer reiterates that Officer Stante was acquitted by a jury in 2002, and cleared by the Police Ethics Tribunal for inappropriate use of force just this past August 2008. Those are cold, hard facts.

However, there is one eyewitness to the events on the early morning of September 5, 1999 outside the Shed Café on St-Laurent Boulevard who will never get to tell his side, and that’s Jean-Pierre Lizotte himself. Lizotte died subsequent to the substantial injuries he suffered.

Yet, while vigilantly defending Officer Stante almost a decade after the incident in question, Stante’s lawyer goes on to cite Jean-Pierre Lizotte’s extensive criminal record. Dead men tell no tales, as the saying goes.

Fortunately, in the case of Jean-Pierre Lizotte, despite two decades in-and-out of prison, this particular dead man had a lot to say, and he said it, poignantly and insightfully. He deserves his voice too, in these pages, as much as Officer Stante has his voice through his lawyer’s skillful advocacy.

Thanks to a remarkable radio program called Souverains anonymes, which encouraged the creative side of prisoners at Bordeaux, we still have a record of many of Jean-Pierre Lizotte’s words.

After learning of his death, the producers of Souverains Anonymes recalled something Lizotte wrote to Abla Farhoud — a Quebec playwright, writer and actress, originally from Lebanon — who had participated in one show at the Bordeaux prison. Lizotte was responding to the words of the main character of Farhoud’s novel, Le bonheur a la queue glissante, who observed, “My country is that place where my children are happy”.

As an immigrant rights activist, deeply immersed in migrant justice struggles, and indelibly touched by my mother’s own immigrant experience, Lizotte’s response to Farhoud is moving, as he seeks common ground while reflecting on his own life; it’s worth citing in full:

“Hello Abla, my name is JP Lizotte. For the 21 years that I’ve been returning inside, prison has become my country. When I leave it, I become an immigrant! I experience all that an immigrant might experience when they miss their country of origin. When I’m inside, I want to leave. And when I’m outside, I miss the inside. Sometimes I say to myself, “If I had a grandmother or a grandfather, things would have been different for me.” But how can you have a grandmother when you’ve hardly had either a mother or father. The memories that I have make me cry, so I won’t tell them to you. But, a grandmother, like the one in your novel, is not given to everyone. So, I say to everyone who has a grandmother or grandfather, take advantage of it. Thanks.”

There are clear underlying and understandable reasons why Lizotte was in-and-out of prison for more than two decades, beyond the list of criminal offenses that Officer Stante’s lawyer provides, without any context.

His fellow prisoners dubbed Lizotte the “Poet of Bordeaux”, and he wrote prolifically. His poems were in a rhyming and often humorous style that address deeply personal themes: his difficult childhood, his lack of a caring mother, his father’s alcoholism, depression, his HIV-positive status, his drug problems, along with subjects like music, prison and revolt. He even wrote an unpublished memoir about his itinerant life called, Voler par amour, pleurer en silence.

Jean-Pierre Lizotte came from a harsh-lived reality, right from his childhood, as he shared in his poems and writings with simple honesty.

On the late night of September 5, 1999, on a trendy and expensive part of St-Laurent Boulevard, Jean-Pierre Lizotte’s reality came up against the contrasting reality of restaurant patrons, bouncers, and police officers. Lizotte was allegedly causing some sort of disturbance, and he had to be restrained in a full-nelson hold and punched at least two times by Officer Stante’s own testimony (some witnesses claim that Lizotte was punched “repeatedly” and excessively). According to eyewitnesses, there was a pool of blood left at the scene. One eyewitness refers to Lizotte being thrown into a police van “like a sack of potatoes”.

Officer Stante was duly acquitted by a jury in 2002; so were the officers in the infamous Rodney King beating, or more recently the New York City officers who shot and killed the unarmed Sean Bell on the day of his wedding. Police officers are routinely acquitted – if ever charged — within a criminal justice system that appropriately demands proof “beyond a reasonable doubt” before conviction.

Officer Stante might stand acquitted, but it’s still completely valid, and necessary, to question the actions of the Montreal police, despite the police procedures that apparently allow for the punching of an unarmed man held by another officer for the purposes of restraining a suspect. One simple fact that readers should consider: the police did not reveal Jean-Pierre Lizotte’s death in 1999 to the public until 53 days later.

But, what if there was a video of what happened outside the Shed Café in 1999 instead of the imperfect and contradictory memories of eyewitnesses at 2:30 in the morning? What if Jean-Pierre Lizotte was present in the courtroom, in a wheelchair and paralyzed, in front of the jury’s own eyes?

At Stante’s trial, and again in your pages, Officer Stante’s lawyer puts a dead man who can’t defend himself on trial. Lizotte transparently acknowledged who he was. What’s cheap is to still deny Jean-Pierre Lizotte – the homeless “criminal” — his full humanity and dignity, because he possessed it in such abundance.

– Jaggi Singh (September 2008), member of Justice for Victims of Police Killings and Solidarity Across Borders (Cité sans frontières / Solidarity City / Ciudad Solidaria (Montréal))

Quebec City: If you’re not anti-fascist, what are you then?

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

Québec City, September 5, 2017 — Earlier today a group of anti-racist/anti-fascist organizers dropped a series of banners. This action is a part of an ongoing and decentralized struggle against Québec right-wing extremists and white nationalists promoting xenophobic, anti-immigrant and racist views. The banners, displayed prominently along major arteries during the morning commute, read “Si tu n’es pas anti-fasciste, t’es quoi alors?” (Translation: “If you’re not anti-fascist, what are you then?”)

Anti-fascism is anti-racist action.

We denounce the practices of scapegoating and fear-mongering that targets Muslims and other racialized immigrant groups. Such practices both implicitly and explicitly blame these groups for the consequences of neoliberal capitalism.

We also denounce the state detention of Haitian and other migrants for fleeing across arbitrary borders without the approval from the colonial state as well as the recent, highly-mediatized campaign against a man of colour for his political activism.

This is not a time for debate or false equivalencies. Far-right groups are growing in visibility and influence in Quebec – they promote and defend white supremacy and ongoing colonialism, often with the tacit support of the police. White nationalists have drawn the lines of engagement, demonstrating hatred and contempt for immigrants, people of colour, Indigenous peoples, people of non-Christian faiths and backgrounds, and anyone else who disagrees with their political vision. In this context, there is no principled neutral position. We call on people everywhere to join us in taking anti-fascist action.

How to make molotovs!

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

Disclaimer: This video is intended purely for informational purposes only, and does in no way encourage or condone any illegal activity.

Languages: français | українська

We think that it’s important for confrontational tactical knowledge to be widespread for the coming storms of revolt. Confrontational tactics can make us safer, because the police become afraid. We need to be careful when playing with fire, but with care, molotovs can greatly increase our power in the streets.

Ingredients:

Empty 500ml beer bottles

Gloves

Gasoline

Motor oil

Funnel

Gauze or strips of t-shirt

Duct tape

Never touch any of your materials without gloves, to avoid transferring fingerprints.

First, fill the beer bottle half-way with a mixture of 2/3 gasoline and 1/3 motor oil. Adding motor oil makes the fire burn longer and bigger. Leaving empty space in the bottle makes it fill with gas-fumes, which will make the molotov more explosive.

For the fuse (shirt or gauze), tie a knot that will fit in the entrance to the bottle, 1 inch from the top. The fuse should reach the gasoline. If you turn the bottle upside down, the knot should hold. Use duct-tape to make the opening more air-tight, because gasoline evaporates.

For larger molotovs, you can use a wine bottle that has a cap you can twist back on. Perrier works too.

Beer-bottle molotovs can be transported in the packaging. Seal them in a garbage bag to diminish the smell of gasoline, and to keep them clean of fingerprints.

It’s safest to not wait more than 30 seconds to throw after the molotov is lit.

Stay safe! Stay fierce!

The River Camp is there to stay!

From Camp de la Rivière

Yesterday’s torrential downpour forced us to have a slow evening. Lit by the glow of candles and lulled by the drip of raindrops on tarps, some of us played Scrabble, while others read out loud. Today, despite the constant drizzle, the mood remains energetic at the River Camp. We have learned that Junex will suspend work for four months, providing time for the MMS as well as the band councils of Gespeg, Gesgapegiag and Listuguj to hold public consultations for the residents of these three reserves to give input on fossil fuel development projects on unceded Mi`gmak territory.

Three weeks ago, an anonymous blockade of the access road to the Galt sites considerably destabilized the oil company, which until this point had been operating under the radar as much as possible, not even having held a preliminary public consultation on their project. We want to underscore the fact that this new development, which was announced yesterday by the band councils, would probably never have happened without the enormous efforts of the many people struggling on the ground: those who were active during the blockade, the indigenous people and settlers who have been working together at the River Camp, as well as the environmental groups who have been struggling for years in Gaspésie.

The River Camp is alive, active, and here to stay. The temporary halt of Junex’s work is no guarantee that the work will stop forever, nor does it signal the end of fossil fuel exploitation on the territory. We are thus determined to pursue this struggle. The River Camp is a place for organizing, sharing information and exchanging ideas. The need for such spaces, which inspire and make waves far beyond the limits of the camp as such, remains essential. We want an active public conversation, one that takes place horizontally, and it is this that we will continue to nurture. The strength of the relationships created or maintained by the camp is significant.

In this perspective, we reaffirm our call for a week of actions, starting with a demo in Gaspé on the 4th of September. Join us for the march at 14h, after a delicious corn roast! And pass by the Camp by the River at any time, whether for a brief stay, to talk around the fire, or for a long term involvement. We also invite you to our banner-making and circus workshops, as well as a slam night on September 2nd. The last rays of summer sunshine are giving way to the coolness of autumn, and we are still there, enthousiastic and determined.