Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

Originally published March 20, 2020

The situation changes quickly. Along with everyone else, I follow it avidly and share updates, watch our lives change from day to day, get bogged down in uncertainty. It can feel like there is only a single crisis whose facts are objective, allowing only one single path, one that involves separation, enclosure, obedience, control. The state and its appendages become the only ones legitimate to act, and the mainstream media narrative with the mass fear it produces swamps our ability for independent action.

Some anarchists though have pointed out that there are two crises playing out in parallel — one is a pandemic that is spreading rapdily and causing serious harm and even death for thousands. The other is crisis management strategy imposed by the the state. The state claims to be acting in the interest of everyone’s health — it wants us to see its response as objective and inevitable.

But its crisis management is also a way of determining what conditions will be like when the crisis resolves, letting it pick winners and losers along predictable lines. Recognizing the inequality baked into these supposedly neutral measures means acknowledging that certain people being asked to pay a much higher cost than others for what the powerful are claiming as a collective good. I want to recover some autonomy and freedom of action in this moment, and to do this, we need to break free of the narrative we are given.

When we let the state control the narrative, the questions that are asked about this moment, we also let them control the answers. If we want a different outcome than the powerful are preparing, we need to be able to ask a different question.

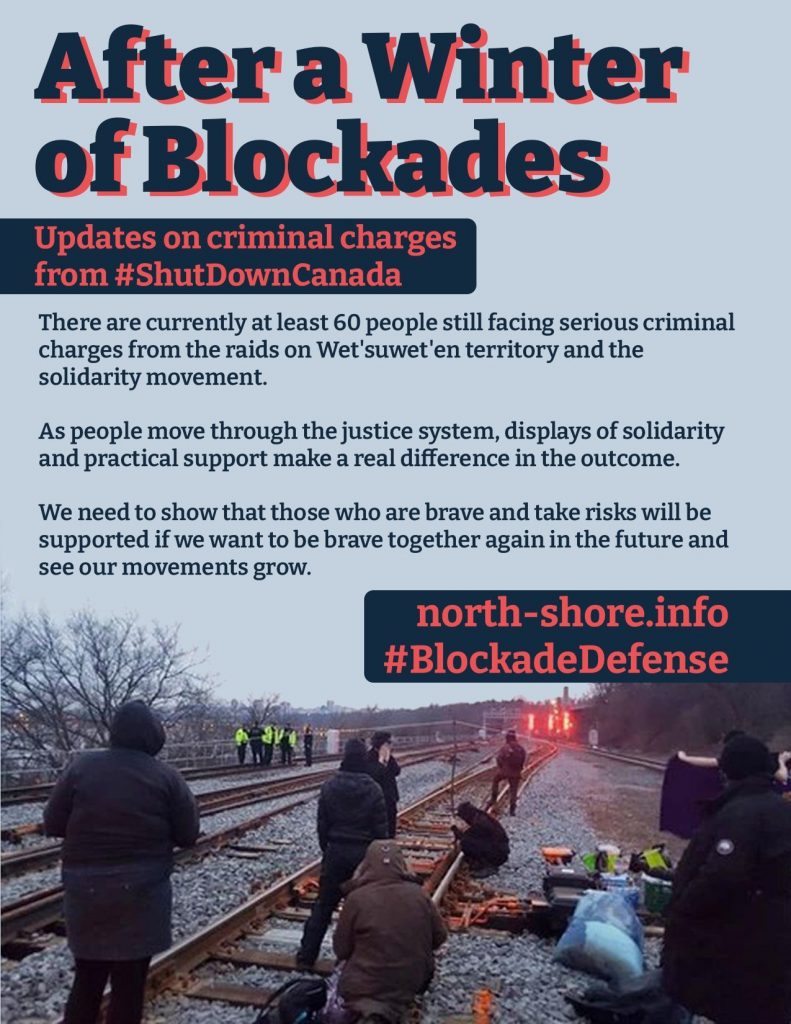

We mistrust the mainstream narrative on so many things, and are usually mindful of the powerful’s ability to shape the narrative to make the actions they want to take seem inevitable. Here in Canada, the exaggeration and lies about the impacts of #shutdowncanada rail blockades was a deliberate play to lay the groundwork for a violent return to normal. We can understand the benefits of an infection-control protocol while being critical of the ways the state is using this moment for its own ends. Even if we assess the situation ourselves and accept certain reccomendations the state is also pushing, we don’t have to adopt the state’s project as our own. There is a big difference between following orders and thinking independently to reach similar conclusions.

When we are actually carrying out own project, it becomes easier to make an independent assessment of the situation, parsing the torrent of information and reccomendations for ourselves and asking what is actually suitable for our goals and priorities. For instance, giving up our ability to have demonstrations while we still need to go work retail jobs seems like a bad call for any liberatory project. Or recognizing the need for a rent strike while also fear mongering about any way of talking to our neighbours.

Giving up on struggle while still accomodating the economy is very far from addressing our own goals, but it flows from the state’s goal of managing the crisis to limit economic harm and prevent challenges to its legitimacy. It’s not that the state set out to quash dissent, that is probably just a byproduct. But if we have a different starting point — build autonomy rather than protect the economy — we will likely strike different balances about what is appropriate.

For me, a starting point is that my project as an anarchist is to create the conditions for free and meaningful lives, not just ones that are as long as possible. I want to listen to smart advice without ceding my agency, and I want to respect the autonomy of others — rather than a moral code to enforce, our virus measures should be based on agreements and boundaries, like any other consent practice. We communicate about the measures we choose, we come to agreements, and where agreements aren’t possible, we set boundaries that are self-enforceable and don’t rely on coercion. We look at the ways access to medical care, class, race, gender, geography, and of course health affect the impact of both the virus and the state’s response and try to see that as a basis for solidarity.

A big part of the state’s narrative is unity — the idea that we need to come together as a society around a singular good that is for everyone. People like feeling like they’re part of a big group effort and like having the sense of contributing through their own small actions — the same kinds of phenomenons that make rebellious social movements possible also enable these moments of mass obedience. We can begin rejecting it by reminding ourselves that the interests of the rich and powerful are fundamentally at odds with our own. Even in a situation where they could get sicken or die too (unlike the opioid crisis or the AIDS epidemic before it), their response to the crisis is unlikely to meet our needs and may even intensify exploitation.

The presumed subject of most of the measures like self-isolation and social distancing is middle-class — they imagine a person whose job can easily be worked from home or who has access to paid vacation or sick days (or, in the worst case, savings), a person with a spacious home, a personal vehicle, without very many close, intimate relationships, with money to spend on childcare and leisure activities. Everyone is asked to accept a level of discomfort, but that increases the further away our lives are from looking like that unstated ideal and compounds the unequal risk of the worst consequences of the virus. One response to this inequality has been to call on the state to do forms of redistribution, by expanding employment insurance benefits, or by providing loans or payment deferrals. Many of these measure boil down to producing new forms of debt for people who are in need, which recalls the outcome of the 2008 financial crash, where everyone shared in absorbing the losses of the rich while the poor were left out to dry.

I have no interest in becoming an advocate for what the state should do and I certainly don’t think this is a tipping point for the adoption of more socialistic measures. The central issue to me is whether or not we want the state to have the abiltiy to shut everything down, regardless of what we think of the justifications it invokes for doing so.

The #shutdowncanada blockades were considered unacceptable, though they were barely a fraction as disruptive as the measures the state pulled out just a week later, making clear that it’s not the level of disruption that was unacceptable, but rather who is a legitimate actor. Similarly, the government of Ontario repeated constantly the unacceptable burden striking teachers were placing on families with their handful of days of action, just before closing schools for three weeks — again, the problem is that they were workers and not a government or boss. The closure of borders to people but not goods intensifies the nationalist project already underway across the world, and the economic nature of these seemingly moral measures will become more plain once the virus peaks and the calls shift towards ‘go shopping, for the economy’.

The state is producing legitimacy for its actions by situating them as simply following expert reccomendations, and many leftists echo this logic by calling for experts to be put directly in control of the response to the virus. Both of these are advocating for technocracy, rule by experts. We have seen this in parts of Europe, where economic experts are appointed to head governments to implement ‘neutral’ and ‘objective’ austerity measures. Calls to surrender our own agency and to have faith in experts are already common on the left, especially in the climate change movement, and extending that to the virus crisis is a small leap.

It’s not that I don’t want to hear from experts or don’t want there to be individuals with deep knowledge in specific fields — it’s that I think the way problems are framed already anticipate their solution. The response to the virus in China gives us a vision of what technocracy and authoritarianism are capable of. The virus slows to a stop, and the checkpoints, lockdowns, facial recognition technology, and mobilized labour can be turned to other ends. If you don’t want this answer, you’d better ask a different question.

So much of social life had already been captured by screens and this crisis is accelerating it — how do we fight alienation in this moment? How do we address the mass panic being pushed by the media, and the anxiety and isolation that comes with it?

How do we take back agency? Mutual aid and autonomous health projects are one idea, but are there ways we can go on the offensive? Can we undermine the ability of the powerful to decide whose lives are worth preserving? Can we go beyond support to challenge property relations? Like maybe building towards looting and expropriations, or extorting bosses rather than begging not to be fired for being sick?

How are we preparing to avoid curfews or travel restrictions, even cross closed borders, should we consider it appropriate to do so? This will certainly involve setting our own standards for safety and necessity, not just accepting the state’s guidelines.

How do we push forward other anarchist engagements? Specifically, our hostility to prison in all its forms seems very relevant here. How do we centre and target prison in this moment? How about borders? And should the police get involved to enforce various state measures, how do we delegitimate them and limit their power?

How do we target the way power is concentrating and restructuring itself around us? What interests are poised to “win” at the virus and how do we undermine them (think investment opportunities, but also new laws and increased powers). What infrastructure of control is being put in place? Who are the profiteers and how can we hurt them? How do we prepare for what comes next and plan for the window of possibility that might exist in between the worst of the virus and a return to economic normalcy?

Developing our own read on the situation, along with our own goals and practices, is not a small job. It will take the exchange of texts, experiments in action, and communication about the results. It will take broadening our sense of inside-outside to include enough people to be able to organize. It will involve still acting in the public space and refusing to retreat to online space. Combined with measures to deal with the virus, the intense fear and pressure to conform coming from many who would normally be our allies makes even finding space to discuss the crises on different terms a challenge. But if we actually want to challenge the ability of the powerful to shape the response to the virus for their own interests, we need to start by taking back the ability to ask our own questions.

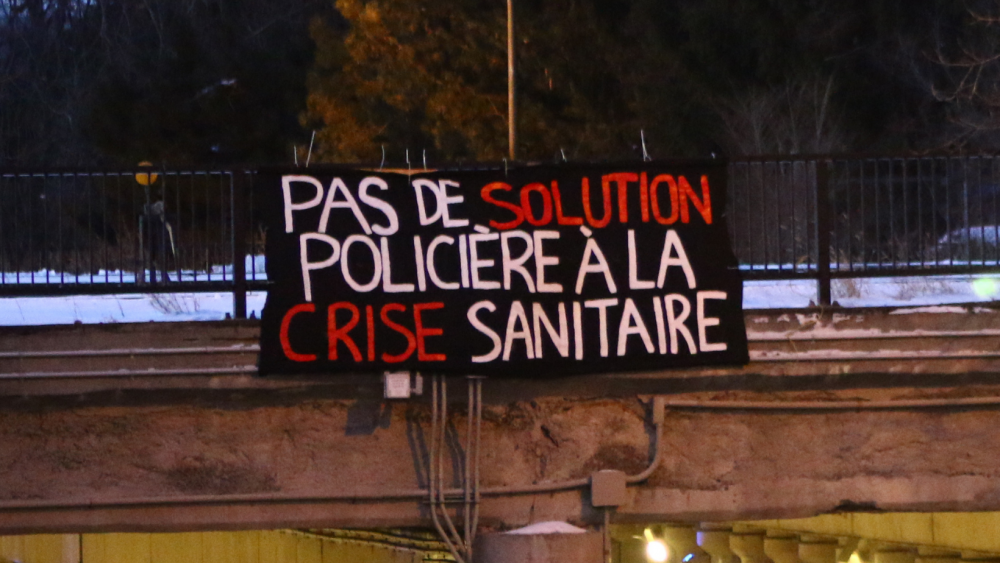

Conditions are different everywhere, but all states are watching each other and following each others’ lead, and we would do well to look to anarchists in other places dealing with conditions that may soon become our own. So I’ll leave you with this quote from anarchists in France, where a mandatory lockdown has been in place all week, enforced with dramatic police violence:

And so yes, let’s avoid too much collectivity in our activities and unnecessary meetings, we will maintain a safe distance, but fuck the confinement measures, we’ll evade your police patroles as much as we can, it’s out of the question that we support repression or restrictions of our rights! To all the poor, marginal, and rebellious, show solidarity and engage in mutual aid to maintain activities necessary for survival, avoid the arrests and fines and continue expressing ourselves politically.

From “Against Mass Confinement” (“Contre le confinement généralisé“). Published in French on Indymedia Nantes