From sub.Media

At 8:00am on the morning of Jan 8th, a group of roughly 25 people shut down the Jacques Cartier Bridge – a vital transportation corridor in so-called “Montreal” – in response to the RCMP’s attack on the Wet’suwet’en.

From sub.Media

At 8:00am on the morning of Jan 8th, a group of roughly 25 people shut down the Jacques Cartier Bridge – a vital transportation corridor in so-called “Montreal” – in response to the RCMP’s attack on the Wet’suwet’en.

From From Embers

This episode features two interviews with organizers of New Years Eve noise demonstrations in Hamilton and in Montreal. We talk about the rage and sadness we feel about the existence of prisons, noise demonstrations, building traditions and rituals, and our favourite New Years Eve stories.

Links:

Seven Years Against Prison (2015)

International Call For New Year’s Even Noise Demonstrations (English, 2018)

Anonymous submission to No Borders Media

December 24, 2018 — On Christmas Eve, Montreal-area vandals have covered the John A. Macdonald Monument (1895) and the Queen Victoria Statue at McGill (1900) with red and green paint respectively.

This action, claimed by Santa’s Rebel Elves, continues a series of paint attacks on symbols of racist British colonialism in Montreal. The Macdonald Monument has been vandalized at least six times, while the two Queen Victoria Statues in Montreal have been painted at least three times (including in green paint on St. Patrick’s Day 2018).

Concerning the Queen Victoria statue, the Delhi-Dublin Anti-Colonial Solidarity Brigade, responsible for the St. Patrick’s Day vandalism, wrote:

“The presence of racist Queen Victoria statues in Montreal are an insult to the self-determination and resistance struggles of oppressed peoples worldwide, including Indigenous nations in North America (Turtle Island) and Oceania, as well as the peoples of Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean, the Indian subcontinent, and everywhere the British Empire committed its atrocities.The Queen Victoria statues are also an insult to the legacy of revolt by Irish freedom fighters, and anti-colonial mutineers of British origin. The statues particularly deserve no public space in Quebec, where the Québecois weredenigrated and marginalized by British racists acting in the name of the putrid monarchy represented by Queen Victoria.Queen Victoria’s reign, which continues to be whitewashed in history books and in popular media, represented a massive expansion of the barbaric British Empire. Collectively her reign represents a criminal legacy ofgenocide, mass murder, torture, massacres, terror, forced famines, concentration camps, theft, cultural denigration, racism, and white supremacy. That legacy should be denounced and attacked.”

Concerning the Macdonald Monument, a poster seen on the streets of Montreal concisely sums up his racist legacy as follows:

“John A. Macdonald was a white supremacist. He directly contributed to the genocide of Indigenous peoples with the creation of the brutal residential schools system, as well as other measures meant to destroy native cultures and traditions. He was racist and hostile towards non-white minority groups in Canada, openly promoting the preservation of a so-called “Aryan” Canada. He passed laws to exclude people of Chinese origin. He was responsiblefor the hanging of Métis martyr Louis Riel.Macdonald statues should be removed from public space and instead placed in archives or museums, where they belong as historical artifacts. Public space should celebrate collective struggles for justice and liberation, notwhite supremacy and genocide.” (Poster Link: http://bit.ly/2L0v7a0)

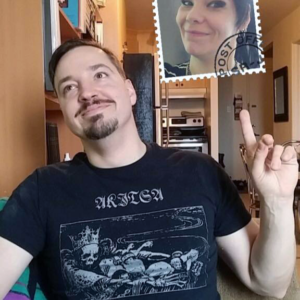

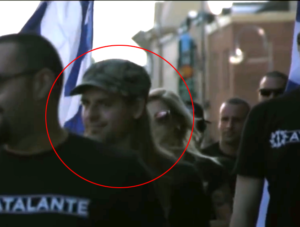

Raphaël Lévesque, the public face of the neofascist group Atalante, really likes the attention his little stunts get him (that’s why he has long since stopped hiding his identity). However, the central role of a single individual should not prevent us from looking at the people who gravitate to his leadership, because a movement like Atalante is nothing without the militants that give it life.

All the actions that the group has carried out in Québec City and Montréal over the past two years to increase its visibility suggest that, along with its more visible members, Atalante can count on a reserve of a few dozen individuals who support the ultranationalist cause. Despite its small numbers, the group has caught the eye of a section of the mainstream media and has made effective use of social media to promote a so-called “national revolutionary” position within Québec’s far right.

The practice of masking up in public clearly indicates that the majority of Atalante’s militants want hide their association with this openly fascist group. We think it is high time to shine a light on the militants and sympathizers of Atalante.

We also think it’s important to clear up any confusion about Atalante’s political project and to expose the group’s direct ties with different fascist currents.

Despite its marginal nature, Atalante managed to make headlines several times in 2017 and 2018, particularly last May, when a handful of its militants burst into the Montréal offices of VICE with the specific intent of intimidating the staff on site that day. The report published a few days later described the incident thusly:

When an employee opened the door for a man holding bouquet of flowers, a group of six or seven men, all masked except one, burst into the main room with the theme music from the The Price Is Right playing on a small Bluetooth speaker. The men then moved on to the newsroom, where they threw around clown noses and hundreds of leaflets . . .

The specifically attempted to intimidate the journalist Simon Coutu—who has written about the group—by gathering in his office to give him a trophy sporting the inscription: “VICE: Média poubelle 2018.”

Raphaël Lévesque, aka Raf Stomper, said the visit was to thank Coutu in the name of “all of the victims of the war you are trying to start.”

In response to this dreary bit of political theatre, Atalante was mentioned in media all over Canada, in the United States, and even in Europe. Beyond that, the action was denounced by Premier Philippe Couillard and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. On a propaganda level, Atalante pulled off a neat little coup with only six people and a limited amount of imagination.[i]

As will become clear, this is Atalante’s modus operandi: putting a minimum of energy into these little propaganda actions that gain a lot of media coverage and create a platform for spreading its ideas, accompanied by the use of Facebook to project an image of strength.

As the only member of the group who had not covered his face, Atalante’s main man, Raphaël “Raf Stomper” Lévesque, faces a variety of charges for the action against VICE, including break and enter, mischief, criminal harassment, and intimidation. This is just the sort of judicial overkill that is more likely to increase his stature (and boost his already substantial ego) than to achieve anything else.

The thirty-five-year-old Lévesque (born August 5, 1983) is well-known to Québec’s antifascists. He has previously been indicted for assault, uttering threats, and drug trafficking, and was in prison as recently as 2016. In 2017, he called for the torching of the offices of the “Centre de prévention de la radicalisation menant à la violence” should the latter act on its stated intention to set up in Québec City. Although the center’s director Mr. Deparice-Okomba said that this constituted a criminal threat, no legal action seems to have been taken in the matter.

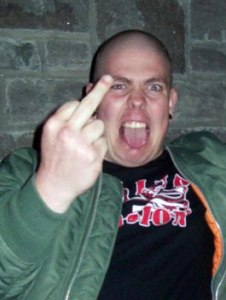

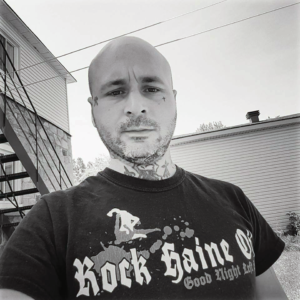

Besides his run-ins with the law, Lévesque is the singer for Légitime Violence, an oï[ii] band that is part of the Rock Against Communism movement[iii], and a known leader of the Québec City Stomper Crew, a bonehead gang[iv] active for a number of years in the Québec City region and known for its ties to organized crime and drug trafficking.

To understand the nature of Atalante today, it is useful to remember that the group grew out of the band Légitime Violence and the bonehead scene around the Québec City Stomper Crew (which is still the heart of the organization).

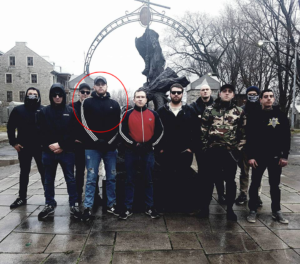

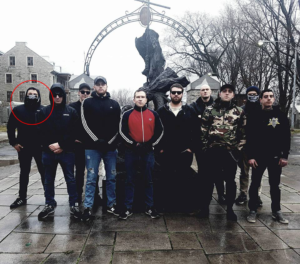

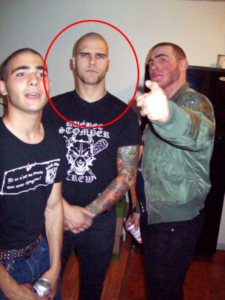

In the early 2000s, two so-called “apolitical” skinhead youth gangs emerged in the province. They were Coup de Masse (CdM) in Montréal and the Québec City Stompers (2004). Although they claimed to be apolitical, both gangs were strong supporters of Québec nationalism, which led to them being pushed out of the underground scenes in their respective cities. Even if the two gangs, which had very close ties, rejected both the left and the right (there are even stories about battles between the Québec City Stompers and the neo-Nazis in the Sainte-Foy Krew in the late 2000s), the Stompers rapidly gravitated to the bonehead milieu, adopting a so-called “anti-antifascist” position. At that point, the Québec City Stompers were Raphaël Lévesque, Yan Barras, and Martin Léger, with the addition over time of Benjamin Bastien, Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau, Yannick Vézina, Olivier Gadoury, Jonathan Payeur, and Roxanne Baron. Even today, there seems to be a distinction between the memberships of Atalante and the Québec City Stompers —the latter being more narrowly focused and countercultural. While all of the current members of the Québec City Stompers are members of Atalante, the inverse is not the case.

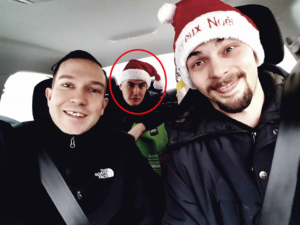

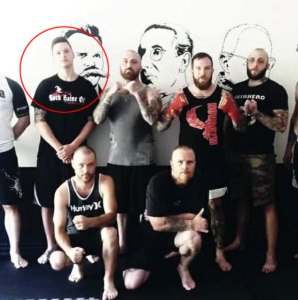

A recent photo of Québec Stompers: Étienne Mailhot-Bruneau, Olivier Gadoury, Raphaël Lévesque, Sven Côté, Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau, Jonathan Payeur, Benjamin Bastien and Yan Barras.

Both of these gangs were enthusiastic aficionados of a musical scene made up of Rock Against Communism (RAC) and Rock Identitaire Français (RIF), two musical styles that are a direct outgrowth of the far-right scene. In Québec, the major bands are Coup de Masse, Section de Guerre, Fleurdelix et les Affreux Gaulois, and Bootprint, joined by Légitime Violence in the late 2000s. A group that could be seen as a major influence on this scene is Trouble Makers, largely associated with RIF. The RIF style is an attempt to package far-right ideas in a slicker and more mainstream musical style than is typical of RAC. Formed in the late 1990s, the members of Trouble Makers are Simon Cadieux, Maxime Taverna, Jonathan Stack, and François-Pierre Stack, the latter three being longstanding identitarian militants, known, among other things, to have been members of different far-right groups, including Québec-Radical and the Affranchistes. Trouble Makers were also the first Québec band to cross the Atlantic to participate in events organized by CasaPound in Italy.

Early in the 2010s, after numerous attempts to form a far-right collective in Montréal, including Troisième Voie Québec, Légion Nationale, and the Faction Nationaliste, Maxime Taverna founded the neofascist groupuscule La Bannière Noire, which eventually became the Montréal chapter of the Fédération des Québécois de Souche (FQS), a precursor to Atalante. With a membership that included Rémi Chabot, Mathieu Bergeron, François-Pierre Stack, and Francis Hamelin, we can already discern the core of what would eventually become Atalante Montréal. Even if rarely active, the collective took on the task of uniting the far-right bonehead scene by organizing identitarian networking soirées and hosting the radio show La bouche de nos canons, broadcast by Bandiera Nera, a chain connected to Zentropa, a far-right media network with ties to CasaPound. Bannière Noire was the first right-wing collective in Québec to openly develop a relationship with the Italian far right and to use imagery similar to what would later be used by Atalante. It is beyond question that the group and its founder Maxime Taverna have played an important role in the creation of Atalante and continue to hold a place as leading ideologues.[v]

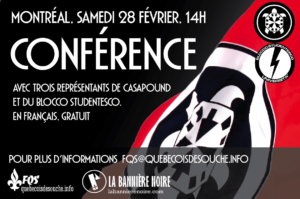

A poster announcing a CasaPound talk organized by Bannière Noire and the Fédération des Québécois de souche, February 28, 2015.

Many former and current members of the nebulous bonehead scene that has existed since the 1990s have taken part in violent attacks, particularly against racialized people.

In 1997, eight associates of the Vinland Hammer Skins and Berzerker Boot Boys were accused of a series of attacks with baseball bats and metal bars, injuring around thirty people in bars around the city. Among them, Jonathan Côté, alias “Jo Wennebago” (Chevrotine Jo on Facebook), remains very close to the Stompers. Steve Lavallée (Steve Bateman on Facebook) was a central figure among neo-Nazis back in the day, particularly as a member of the band Coup de Masse and allegedly as a leader of a short-lived Québec section of Blood & Honour. Today, Lavallée seems to have toned it down, but he still hangs out with the boys from Légitime Violence and Atalante.

On June 22, 2002, Rémi Chabot and Daniel Laverdière gratuitously attacked and stabbed a Haitian worker, Evens Marseille, outside a bar in the Montréal’s East End. Rémi Chabot remains part of the nebulous neo-Nazi scene of which Atalante is the current standard-bearer.

On New Year’s Eve 2007, six of the Stompers, including Raphaël Lévesque, burst in to the Bar-Coop l’AgitéE, a left-wing hangout in Québec City, and one of them, Yan Barras, stabbed six people with an X-Acto knife. Légitime Violence makes reference to this brutal attack in their eponymous song: “Ces petits gauchistes efféminés, qui se permettent de nous critiquer, ils n’oseront jamais nous affronter, on va tous les poignarder!” [These little leftist sissies, who dare to criticize us, wouldn’t have the nerve to face us, we’d just stab them all!][vi]

In 2008, Mathieu Bergeron and an accomplice, Julien-Alexandre Leclerc, were arrested for knifing two Arab youths and attacking a Haitian taxi driver. Bergeron would remain a key figure in the Montréal neo-Nazi scene for a number of years, as a member of the StrikeForce crew, singer for the RAC band Section St-Laurent, and founder of Faction Nationaliste. Today, Bergeron is part of the Atalante inner circle and has participated in many of the group’s actions. Francis Hamelin, another Montréal associate of Atalante, is a longtime friend of Mathieu Bergeron.

Francis Hamelin (left) and Mathieu Bergeron, with members of Troisième Voie Québec, at an anti-Semitic demonstration in the Montréal borough of Hampstead, in 2011. In the middle (with a dog) is Major Serge Provost of the defunct Milice patriotique du Québec. In the back, wearing a black shirt, is Maxime Taverna of La Bannière Noire.

Légitime Violence songs overflow with racism and homophobia (one of them, an Evil Skins cover, has this notable pro-Shoah passage: “Déroulons les barbelés, préparons le Zyklon B!” [Roll out the barbed wire, get the Zyklon B ready!][vii] Before the founding of Atalante in 2016 the band’s influence outside the bonehead scene was fairly limited.

Information about Légitime Violence concerts in Québec City is generally shared in a very controlled word-of-mouth way to avoid reprisals from antifascist groups. They have achieved greater success in Europe, where the band have been able to tour and sell promotional material.

Légitime Violence: Raphaël Lévesque, Jhan Mecteau, Benjamin Bastien & Jean-Seb (missing, Félix Latraverse).

In 2011, the group took a hit, when, responding to public pressure, the Envol et macadam festival in Québec City pulled its concert from the program.

In 2013, the band toured Europe, creating ties with other neo-Nazi bands, and for the first time staking out clear political positions. Two years later, a second tour led members of the group to found a neofascist group on the model of CasaPound (Italy), Hogar Social and Bastion Social (France). The result was Atalante, which was officially founded in 2016.

Légitime Violence also maintains close ties with the RAC and bonehead scene in New York, specifically with the (now defunct) band Offensive Weapon and the label United Riot, which distributed a split recording featuring the two groups in 2013. They also have connections to the 211 Bootboys Crew, a New York City bonehead crew, some of whose members have been found guilty of armed assault and others who currently face charges for beating antifascists outside a recent talk by Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes at the Metropolitan Republican Club in Manhattan.

John Young (left) of the 211 Boot Boys and the Offensive Weapon entourage pleaded guilty to assault and battery in July 2017, in New York. He appears here with Raphaël Lévesque.

As recently as November 2018, members of Légitime Violence went to France to pay their respects to the late Sergei Ventura, a bonehead piece of shit who had been part of Serge Ayoub and Troisième Voie’s entourage.

The group Troisième Voie before its dissolution. In the middle, Sergei Ventura with Serge Ayoub. Between them is Estaban Morillo, who murdered Clément Méric.

Romain, formerly of Troisième Voie, with Raphaël Lévesque, in the Fall of 2018. Note the Skrewdriver t-shirt .

Défends, the Légitime Violence album that came out in 2017, is intended as a sort of self-referential homage . . . to Atalante.

Buoyed by propaganda and street action, Atalante hopes to contribute to an “identitarian renaissance.” The description the group provides of itself on its Facebook page —which has six thousand subscribers— reflects the “declinist” perspective that characterizes a significant segment of the contemporary far right:

In this sombre age, as globalization and consumerism reign, we are being suffocated by the tyranny of political correctness and the negation of our identity. The West is being undermined from within by the collapse of traditional values and principles.

Atalante’s slogan, “to exist is to fight against that which negates my existence” is borrowed from Dominique Venner, a mythic figure on the French far right. Initially a member of the Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS), a far-right paramilitary group that fought against Algerian independence, later he was a historian who advanced the “clash of civilizations” thesis. Venner committed suicide in 2013 at Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris to protest against same-sex marriage.

Atalante is aggressively ultranationalist, identifying with the culture and history of the French Canadian nation, or as Atalante members put it, New France.[viii] The name Atalante refers to the French frigate the Atalante, which ran aground during a battle with the British in 1760. The group’s logo is a ship’s wheel with a lightning bolt cutting through it.

Indeed, Atalante’s worldview draws heavily on the history of Quebec (or French Canada) as an oppressed, conquered, nation. Understanding this history primarily through a cultural and demographic lens, Atalante holds that French Canadians have been subjected to an attempted genocide for centuries. This narrative draws on specific elements of Quebec history, and in the past, for instance in the 1960s, a similar logic led many people to develop a left-wing nationalism that identified with and supported Third World anticolonial movements. In 2018, however, this approach most easily finds its logical extension in far right conspiracy theories about “white genocide”, the “grand remplacement”, or the “Kalergi Plan”, all of which are in fact reference points for Quebec far rightists (including Atalante) today. The fact that the overwhelming majority of Québécois reject this kind of extreme racism is explained away as a result of “degeneracy” and “brainwashing.” This version of Quebec history has been summed up by Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau in an interview with a far-right website in 2017:

(…) the turning point of the creation of this fake nation [Canada] came when the new way to destroy us was introduced – immigration, that came from the ‘report on the affairs of british north America’ made by Lord Durham in 1839, who recommended that the French had to vanish. This happened before Canada became a county [sic] in 1967; the year 2017 is special because they are celebrating the 150th anniversary of this fraud. First they failed their objectives, because they brought Irish Catholics, Italian Catholics, Greek Catholics, Polish Catholics and many other Catholic Europeans; all those foreigners actually adopted our culture and made us even more European and quite unique. After this failed attempt, they realized they had to bring an entirely opposite culture of strangers to mix with us, or to make us an even smaller minority in Canada. So to mask their plan and make it look more attractive for the leftist ‘nationalists’ and other retarded liberals and Marxists, they decided to bring in immigrants that spoke French, such as Haitians and North Africans. The worst part of their plan is that they actually damaged british culture in Canada more than ours – for example, if you visit a city like Toronto it is worse there than in Montréal. However, we now take in more immigrants than France – imagine our future! All of these immigration politics are a plan to exterminate our people.”

Atalante describes itself as “national revolutionary” organisation[ix]. As one militant put it during an interview with the Breizh.info website:

The use of the word revolutionary shocks a lot of people, but it reflects the fact that we don’t want to retain anything from the decadent and sick modern world. What we want to do is create the warrior aristocracy of tomorrow by encouraging our militants to practice intense sports like extreme fighting and weight training and to read all sorts of literature.

We don’t want to preserve this hierarchy, with the wealthiest at the top and the poorest at the bottom, but want to establish a meritocracy that advocates the foundational Western values. By foundational values, we don’t mean the decadent world of the recent past, but the timeless values of heroism, adventure, a sense of sacrifice, honor, and a taste for risk-taking (there are many others, too).

The members of Atalante are primarily inspired by CasaPound, an Italian neofascist movement from which it borrows both elements of discourse (rhetoric that connects anti-immigrant sentiment with anti-capitalism, etc.) and mobilizing tactics (charity initiatives exclusively for “old stock” citizens, etc.).

In August 2016, in collaboration with the Fédération des Québécois de souche, Atalante organized a seminar in Québec City by Gabriele Adinolfi, a pioneering intellectual of the Italian Third Position movement and a supporter of CasaPound. Then in 2017, members of Atalante, including Antoine and Étienne Mailhot-Bruneau, went to Rome for a get-together with fascist militants from CasaPound and the affiliated Blocco Studentesco.

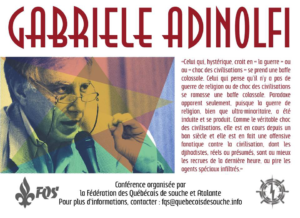

Promotional poster for a Gabriele Adinolfi conference organized by Atalante and the Fédération des Québécois de souche, in August 2016.

Jean-Sébastien, Raphaël, and Benjamin of Légitime Violence, with Sébastien De Boëldieu and Gianluca Iannone, respectively the international spokesperson and National President of CasaPound.

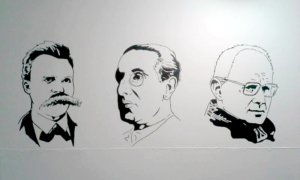

Atalante doesn’t try to hide its admiration for fascist intellectuals. Next to a portrait of Dominique Venner that is painted on the wall of its gym is one of Julius Evola, a figure recognized by many as the most important thinker of the fascist renaissance of the second half of the twentieth century. In March 2018, Atalante posted a homage to the “martyr” François Duprat, a national-revolutionary theorist and major defender of historic fascism, on its Facebook page.

Portraits of Friedrich Nietzsche, Julius Evola, and Dominique Venner on the wall of Atalante’s Québec City gym.

As a national-revolutionary group, Atalante co-opts anti-capitalist themes, notably opposition to the international bourgeoisie (embodied in their rhetoric by the spectre of “globalism” and the mythic Georges Soros),[x] claiming that they are carrying out a war against the white working class by introducing “a cheap foreign workforce” that will undermine the gains of “old stock Québécois.”

Paradoxically, although the national revolutionaries, who detest communists and anarchists in a visceral way, up to wishing for their deaths, aren’t satisfied with just co-opting elements of left-wing theory but also frequently adopt tried and true tactics of the anti-capitalist left. The intervention at the VICE offices, for example, is a style of action picked up from Atalante’s sister organizations in Europe, which those organizations have stolen from the toolbox of the far left they so mortally hate. The same is true of the distribution of clothing and food to impoverished (“old stock”) citizens, which is a central Atalante activity in Québec City and Montréal. Then, of course, there are the banner drops, another proven far-left tactic. One might even think that the contemporary far right is incapable of an original thought. . .

The cosmetic shifts in the identitarian far-right scenes on both sides of the Atlantic (European “identitarians” and the alt-right in the U.S.), including the gradual fine-tuning of their images, with the transformation of brutal and scary neo-Nazi boneheads into clean-cut and disciplined nipsters. As Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau has explained, they “realized that if we wanted more people to join, we had to be more casual and more accessible for people.” This face-lift therefore shows a desire to be perceived more positively and eventually accepted by moderate nationalists, to begin with, and then by ever larger sections of society, with the hope that their particular brand of profoundly racist identitarian ultranationalism, based on a cult of violence, will take root in the population at large.

Atalante’s positions have sometimes led them to adopt a critical posture vis-à-vis other far-right tendencies, particularly the current national-populist movement. For example, although Atalante members showed up at the March 4, 2017, Islamophobic demo in Québec City, they stayed in the background, and in a leaflet later posted on Facebook lamented the fixation of the populist groups on Islam, seeing the true enemies as multiculturalism, “mass immigration,” and the “bankster” system.

Similarly, and in keeping with “Third Position” politics, the banner they deployed that day bore a modified Karl Marx reference: “Immigration: Armée de réserve du Capital” [Immigration: Reserve Army of Capital]. (In a similar vein, in 2017, Atalante members distributed pamphlets outside a book launch of the conservative and Islamophobic columnist Mathieu Bock-Côté, criticizing him and others on the right who do not take a more radical anti-systemic stand.)

This perspective was further elaborated by Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau in the aforementioned interview:

There are some groups such as the Soldiers of Odin, and an internet group called the Meute – these groups focus on stopping the islamization of Canada while defending democracy, but this is not our way at all. We are indeed against non-European immigration, but more importantly we are against a regime that uses immigration to exterminate us. This regime uses third world immigrants for their industries, putting pressure on the local workers and we cannot defend something that is not defendable like democracy. We believe that democracy is the worst regime the world has ever known, a regime built and lead by the bourgeoisie that have only served the establishment and their interests.”

That said, 2017–2018 was marked by a certain rapprochement between the Islamophobic and anti-immigrant national-populist milieu and the small neofascist current to which Atalante belongs. This occurred incrementally as members of these different groups began “liking” the same racist ideas on social media, became “friends,” and took part in the same demonstrations —in some cases ending up side by side in tense standoffs with antifascists— the neofascists starting to get encouraging feedback from reformist and non-aligned right wingers.

The most visible and tangible example of this occurred on November 25, 2017, in Québec City, when members of Atalante and the Soldiers of Odin came down from their position at a distance on the ramparts of the esplanade to join a La Meute and Storm Alliance demonstration “in support of the RCMP” (!) outside the Quebec National Assembly. Members of these latter two groups enthusiastically applauded the fascists and welcomed them with open arms. (Shortly after this surprising convergence, made possible by the repressive actions of the Québec City police against antiracists, two well-known neo-Nazis in Montréal, Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald and Philippe Gendron, the latter a member of the Soldiers of Odin, tried to form a “Montréal chapter” of Atalante.)

Nonetheless, this wasn’t the first time that Atalante members participated in a demonstration of the broader far right alongside national-populists. In a December 2016 VICE article, before Dave Tregget left the Soldiers of Odin to create the Storm Alliance, we find him on the telephone with Raphaël Lévesque, making sure that Atalante members will be coming out for an SoO anti-immigration demonstration. Katy Latulippe, the president of Soldiers of Odin Québec, has also publicly spoken of her great respect for Atalante, adding that the two groups had carried out joint patrols in Québec City (in essence, acts of intimidation directed at immigrants).

An Atalante and Soldiers of Odin demonstration in Québec City, on April 1, 2018, to commemorate the centenary of the draft riots in Québec.

Recall that Katy Latulippe replaced Dave Tregget at the head of Soldiers of Odin Québec in early 2017; she later reiterated her admiration for Atalante:

“We are united on many issues,” the president of the Québec chapter of the Soldiers of Odin, Katy Latulippe, said about Atalante. “There is a great deal of mutual respect between the two groups. They distribute food in the streets and so do we. Why not have the pleasure of helping each other out? We have good chemistry together. Our homeless and out veterans are dying of hunger in the streets. How can you take in people from other countries, when you aren’t capable of taking care of your own people?”

While the ties to the Soldiers of Odin are not insignificant, the Fédération des Québécois de souche is a more important ideological influence on Atalante. The FQS was created in 2007 by Maxime Fiset as an explicitly white supremacist organization (Fiset is now a repentant former Nazi who has patched himself over into a so-called expert on the far right). The FQS magazine Le Harfang was one of the first francophone publications to promote elements of the Alt-Right, and its editors, who use the collective pseudonym “Rémi Tremblay,” have often collaborated with alt-right publications in the U.S. The FQS’s mission could be described as attempting to unite the diverse far-right tendencies in Québec, from traditional Catholicism to the identitarians, while reducing the gap between the generation that was active in the 1980s and the contemporary militant far right.

It is quite likely intercession by the FQS that enabled Atalante to organize public prayer on the Plains of Abraham on May 1, 2016, with a priest from the Fraternité sacerdotale Saint-Pie X (FSSPX)[xi], a traditionalist far-right Catholic organization. The connection with traditionalist Catholicism arose again in May 2017, when Atalante took responsibility for security at a conference in Montréal organized by the Association des parents catholiques du Québec, another far-right organization, with Marion Sigault (an Alain Soral sympathizer) and Jean-Claude Dupuis (from the above-mentioned FSSPX, and previously a member of Cercle Jeune nation).[xii]

A mass officiated by a priest from the Fraternité sacerdotale Saint-Pie X, on May 1, 2016, in Québec City, organized by members of Atalante and the Fédération des Québécois de souche.

Poster announcing a conference with Jean-Claude Dupuis, a close associate of the Fraternité sacerdotale Saint-Pie X, at which Atalante supposedly provided security

In May 2017, the FQS and Atalante joined forces to organize the visit of a militant from the Groupe Union Défense (GUD), a far-right French student organization and an immediate precursor to Bastion Social. In both February and November 2018, as part of its “militant weekends” reserved for “members and sympathizers,” Atalante turned the microphone over to a “Rémi Tremblay” from the FQS…

As mentioned above, Atalante’s public activity basically consists of distributing lunches to (“old stock”) homeless people, paying symbolic homage to various intellectual “heroes” (Jeanne d’Arc, Dominique Venner, the French navigator Jean Vauquelin, etc.), and putting up paper banners with political slogans in quick and furtive nighttime actions.

A look at the slogans on their banners should suffice to provide a clear idea of their politics: “REMIGRATION,” “IMMIGRATION: RESERVE ARMY OF CAPITAL,” “SOCIAL JUSTICE: PRIORITIZE THE NATION,” “TERRORISTS OUT: ISLAM OUT,” “WESTERN SAMURAI” (!), etc.

On one of their public outings in Montréal, in August 2017, Atalante members put up banners demanding “remigration,” particularly around the Olympic Stadium, where Haitian refugees were being temporarily housed.

Atalante views Muslims and racialized people as the swelling ranks of invaders and terrorists who must be expelled. In the face of what they describe as “our quiet extermination,” in the style of far-right European groups like Génération Identitaire, Atalante calls for “a reverse in the flow of migration and a far-reaching remigration accompanied by an effective policy to increase the birth rate.”

“Remigration,” a term that has come into vogue for identitarian movements on both sides of the Atlantic in recent years, essentially designates a programme of ethnic cleansing.

Atalante members have visited Montréal a number of times to sticker, poster, and hang banners. They have received the help of members of their anemic “Montréal chapter,” including Vincent Cyr and Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald (the former anglophone La Meute member who became a local neo-Nazi celebrity following his trip to Charlottesville in August 2017 and his active participation in the “Montreal Storm” neo-Nazi chat rooms under the pseudonym “FriendlyFash”). As we said previously, the increase in these rapid and risk-free incursions has permitted Atalante to achieve a certain visibility in the mass media and on social media.

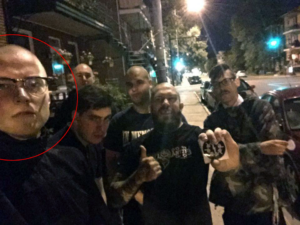

In January 2018, they put up large banners in Montréal denouncing a series of people associated with the left (broadly speaking) and the antiracist movement in the city. Those who were white were denounced as “traitors,” while people of colour were classified as “parasites.” (Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald, Véronique Stewart, David Leblanc, and Martin Minna were identified as having participated in the action, thanks to the latter’s ineptitude.)

Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald, Véronique Stewart, David Leblanc and Martin Minna, following a banner-hanging action in Montreal, January 2018.

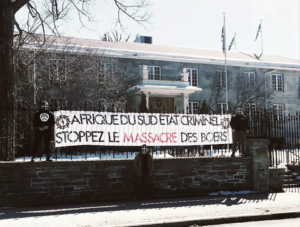

In August 2018, during another postering run, Atalante took up the conspiracy theory in vogue in white supremacist circles that the white farmers in South Africa are the victims of a “genocide” at the hands of the country’s black majority. This conspiracy theory has, in fact, been completely debunked, which hasn’t prevented members of Atalante (including Beauvais-MacDonald, yep, him again) from going to the South African embassy in Ottawa to unfurl a ridiculous banner denouncing the “massacre of Boers.”

Atalante banner unfurled at the office of the High Commissioner for South Africa, in Ottawa, March 2018. On the left, Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald.

In August 2018, Atalante militants in Montréal attacked passersby who objected to the content of the stickers they were posting, uttering threats and screaming at a woman to “go back to your own country.”

In September 2018, during the provincial election, Atalante put up posters on the electoral offices of candidates from the four main parties, denouncing the election as a farce. On its Facebook page, Atalante said it carried out this action because there is “no major difference between the parties’ programmes, other than a lot of nonsense. No inspiring national project capable of serving the common good.” Once again a very minor action that would have been ignored by the media had the left done it got Atalante headlines. As Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau has said regarding the media reaction to these stunts, “with all the people writing to us and encouraging us, journalists are really doing a good job of creating publicity.”

Although these minor actions in Montréal got some attention, the group is much more active in Québec City, where members gather regularly as a scene and wander the streets distributing bag lunches, pose in masks adorned with the fleur-de-lis (a practice copied directly from CasaPound), or clean up graffiti judged to be anti-national, later publishing photo albums of their exploits on Facebook.

Among the notable Atalante actions in Québec City was the creation of an “identitarian fight club” (opened, it would seem, in June 2017) named La Phalange, which serves simultaneously as a social space and a training centre for far-right militants.

It should be noted that the private events organized by Atalante appear to be opportunities to train its militants to carry out nighttime postering campaigns. Last February, Radio-Canada reported that the “militant weekend” mentioned above was held at Domaine Maizerets in Québec City, a publicly funded institution:

The event prospectus specifies a workshop on suvivalism and a conference with spokespeople from the Fédération des Québécois de souche and another national-revolutionary group.

The group’s masked militants took advantage of this gathering to stick up large banners all over Québec City during the night that read “Québec City, Nationalist Stronghold.” Photos of these banners were posted on Facebook.

Atalante’s relative success is doubtless the result of a complex variety of factors, including the current resurgence of the identitarian right, the effective use of social media to reintroduce certain people and tendencies, and the media’s taste for sensational accounts of bad boys and sordid tales. Nonetheless, the radical left shouldn’t overlook certain tactical elements adopted by Atalante that reflect a genuine political acuity: a small group of dedicated militants can carry out simple targeted actions that spark the imagination and have an impact.

We need to understand that Atalante aspires to develop a coherent and revolutionary theoretical framework, which is not the case with the right-wing national-populist groups like La Meute. To the degree that they effectively establish and adhere to such a theoretical framework, the militants of Atalante will be better positioned than the national-populists and even than some of their liberal critics. Their repugnant ideology will necessarily limit the organization’s recruiting potential, but an eventual crisis could provide the group with an opportunity to effectively intervene and become a genuine movement. The worst-case scenario would be a fascist group occupying the political space that should be seized by the revolutionary left.

Let’s not wait until Atalante becomes as important and influential as groups like CasaPound or Generation Identity to organize to block its expansion. Let’s mobilize now to expose and deconstruct its political project and replace it with a social project that is revolutionary, anti-capitalist, egalitarian, and radically antiracist.

Let’s not lose sight of the fact that even in the absence of a crisis situation on which to capitalize, Atalante represents a genuine threat to that sector of the population that is directly targeted by its discourse, as well as to the comrades organizing in areas where it has a presence. Furthermore, a group like Atalante, as we have frequently repeated, constitutes a sort of pole of attraction offering a reference point and gateway for members of the larger national-populist right.

Consequently, it’s necessary to take Atalante seriously, even if the group only numbers a few dozen members whose activity consists largely of putting up banners and cleaning up graffiti.

We can’t encourage our readers enough to take seriously remaining informed and to share information with local antifascist collectives, or form collectives where there are none.

It is only if we are more numerous and better organized than the fascists that we can hope to block their way.

No pasarán!

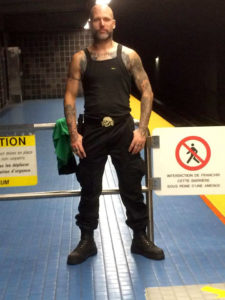

Here’s a rogue’s gallery of individuals we have succeeded in identifying from Atalante, Légitime Violence, and the Québec Stompers’ actions and social media networks. People who belong to Atalante and its satellite groups proudly embrace neofascist ideas and a neofascist project. If you have any information about these people that could be of use to antifascists, don’t hesitate to contact us at renseignements @ riseup.net.

| Raphaël Lévesque, aka Raf Stomper [Québec Stomper/Légitime Violence/Atalante] Singer for Légitime Violence, founder of Atalante. After delivering Thai food for a few years, he moved on to trucking with the company Transport Morneau. However, in court he described himself as a “professional musician.” He has made a few trips to Europe in recent years, specifically to visit the neofascist militants of Bastion Social and CasaPound.    |

| Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau – aka Tony Stomper, aka Antoine Pellerin, “Tony Quechault” on Facebook [Québec Stomper/Atalante] After growing up in Mont-Laurier, like his younger brother Étienne, Antoine began college studies at Lionel-Groulx and participated in the 2007 student movement. He subsequently moved to Québec City, where he joined the Québec Stompers. He then began to study in Rimouski to be a seaman, where he recruited Yannick Vézina. He later studied to teach history at Université Laval, but quickly dropped out of the program. His brother Étienne also joined him in the Stompers, with some close friends from Mont-Laurier, including Dominic Brazeau. Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau appears to be a major Atalante militant, possibly its actual ideological leader. Although he claimed to have nothing to hide in a 2017 interview with the fascist site Zentropa Serbia, he has been very careful to keep his role in Atalante a secret, rarely appearing at the group’s public actions, blurring his face in the rare video in which he appears surreptitiously, and operating under various pseudonyms.      |

| Jonathan Payeur, aka Jo Stomper [Québec Stomper/Atalante] Former antiracist skinhead, in recent years Jonathan Payeur has become Raphaël Lévesque’s lapdog. To improve his image for his new white supremacist friends, he has become very active in Atalante and in the more restricted Québec Stompers crew. Roxanne Baron is his partner. One of his main “heavy responsibilities” is to paint all of the silly banners that Atalante places on billboards long enough to take an out of focus and badly framed photo that will be posted on Facebook the same evening.     |

| Benjamin Bastien, aka Ben Stomper [Québec Stomper/Légitime Violence/Atalante] Guitarist for the band Légitime Violence and a key member of the Québec Stompers, Benjamin Bastien has been an active Atalante member since its formation. Originally from Amos, Benjamin was briefly an antiracist, before becoming “apolitical,” and finally an ultranationalist with bonehead connections.    |

| Yannick Vézina, alias Yan Sailor [Québec Stomper /Atalante] Recruited by Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau during his marine studies in Rimouski, Yannick Vézina (alias Yan Sailor) has been active in Atalante since the group was formed. He was identified in photos of the action at the Montréal VICE offices.     |

| Roxanne Baron, alias Rox Stomper [Québec Stomper/Atalante] An Atalante member in Québec City who has been present at many postering and food distribution outings. Jonathan Payeur’s partner.    |

| Étienne Mailhot-Bruneau [Québec Stomper/Atalante] Originally from Mont-Laurier. Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau’s younger brother. Atalante’s illustrator and graphic designer (under the pseudonym Sam Ox), Étienne has been part of the Stompers’ scene for a number of years and appears to have been a full member in good standing for a while now. Everything suggests that Étienne is a key Atalante member.    |

| Yan Barras [Québec Stomper/Atalante] A longstanding member of the Québec Stompers, he is noted for his key role in the knife attack on AgitéE, on December 31, 2006.   |

| Olivier Gadoury [Québec Stomper/Atalante] Present at the founding of Atalante and at several subsequent events.     |

| Sven Côté [Québec Stomper/Atalante] “Svein Krampus” on Facebook. An Atalante member since the winter of 2016. He began to radicalize in 2013, eventually embracing fascism. He grew up and still lives in Québec City. There is a strong suspicion that Côté was behind the attack on the bookstore La Page Noire in Québec City during the night of December 8–9, 2018.     |

| Valéry Lévesque [Atalante] Raphaël Lévesque’s brother Valéry has been a regular fixture in the Québec Stompers scene for years.   |

| Gabriel Bolduc-Hamel [Atalante] Active for a year in Atalante postering and food distribution in Québec City. He has pulled back from the actions but remains active on social media. He is a tattoo artist.    |

| Renaud Lafontaine [Atalante] Known to be involved in Atalante actions in Québec City, Lafontaine was also part of the Atalante action at the VICE offices in Montréal.    |

| Dominic Brazeau [Atalante] Originally from Mont-Laurier, where he attended school with Étienne Mailhot-Bruneau. Brazeau has participated in a number of Atalante actions since the group was formed.     |

| Simon Gaudreau Participated in a number of Atalante actions in 2018.     |

| Nicolas Bergeron The subject of a recent report by VICE, Bergeron directs a “Viking re-enactment” company, Vinland Productions, that is contracted to animate historical re-enactments for primary and secondary school students in Québec City. Bergeron acknowledges being close to Atalante, which he describes a group that aspires to help the community, and to training at the group’s gym, but denies ever having been a member. However, VICE published photos of him posing with Raphaël Lévesque and participating in Atalante demonstrations. He also sports a number of racist and neo-Nazi tattoos, including the “black sun.” Note that “Vinland” (the name Viking explorers gave to the territory now called Newfoundland) has been a common neo-Nazi trope in Québec for thirty years now.     |

| Benjamin Peelman [Atalante] “Peel Bastion”on Facebook. French expat from the Lille region. An Atalante sympathizer from the get-go.     |

| Mathieu Beaudin [Atalante] Young Atalante sympathizer spotted at a number of actions; for example, the torchlight march in August 2016.     |

| Jhan Mectau [Légitime Violence] Bassist for Légitime Violence and tattoo artist under the name Jhan Art. A live action role-playing (LARP) enthusiast.    |

| Félix Latraverse [Légitime Violence] Pelage Delatravars on Facebook. The new Légitime Violence guitarist. He has participated in some Atalante actions. He is part of the band Folk You! which has ties to neo-Nazi movements, and is a fan of Nation Socialist Black Metal (NSBM). He has toured with a number of bands, notably Dèche-Charge, Neurasthène, Délétère, and Haeres, among others. He works at Studio Sonum, the only place where Légitime Violence is still able to perform.     |

| Gérôme Tymchuk-Leblanc Atalante sympathizer who trains at the La Phalange boxing club.   |

| Alexandre Normand Atalante sympathizer. Active member of the Canadian Armed Forces. Normand was the subject of various articles in 2015 revealing his racist beliefs and his links to the far right.   |

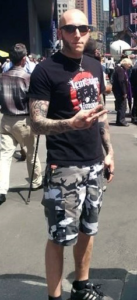

| Vincent Cyr [very active] Comes out of the South Shore hardcore punk scene (he lives in Longueuil). He is now part of the shaky Atalante Montréal initiative. He is a butcher who revels in showing off his profession. Central in the Montréal poster runs and prolific with stickers, he is one of Atalante’s principal propagandists in Montréal. Lacking much in the way of communication skills, he tends to simply replicate the campaigns of the (very small) minds in Québec City. He pleaded guilty to armed assault in 2012.     |

| Shawn Beauvais-Macdonald [very active] Initially an “anglophone” member of La Meute (first noted at the demonstration against Bill 103, on March 4, 2017, where he quickly got involved in a shouting match, denouncing antiracists as “race traitors”). Above all, Beauvais-MacDonald gained attention for participating in the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, in August 2017. Very active in the Montréal alt-right scene, particularly on the neonazi « Montreal Storm » discussion group under the pseudonym « FriendlyFash » and on social media in general. He grew closer to Atalante Québec after meeting Raphaël Lévesque and training at the La Phalange boxing club in Québec City. Along with the bonehead Philippe Gendron, he attempted to gather together a group of people to form a Montréal chapter of Atalante, without a whole lot of success. He participates in most of the Montréal group’s covert actions and seems to be trying to draw the Québec alt-right fringe to Atalante. He participated in the Atalante action at the VICE offices.    |

| Philippe Gendron [deactivated] Bonehead from the Joliette area who began his activist life with the Soldiers of Odin. He formed the alleged “Montréal chapter” of Atalante with Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald. After a run-in with some of the city’s antifascists in the summer of 2018, Gendron hightailed it to Québec City to seek refuge in the steroid-enhanced arms of the Québec Stompers. He seems to have been benched by his comrades-in-arms, who have figured out that he’s not the most reliable of militants or the brightest bulb in the marquee. On top of which, he collaborated with the police . . . oops.     |

| Mathieu Bergeron [active] Found guilty of a racist armed assault in 2008, while he was still a minor, Bergeron would remain an important figure for several years in the Montreal ultranationalist and neo-Nazi scenes, notably as a member of the StrikeForce crew, as singer in the Section St-Laurent group and as founder of the Faction Nationaliste group. Bergeron took part in several of the postering actions in Montreal.    |

| Jean “Brunaldo” [French expat, active] Present at some outings and postering runs in Montréal and Québec City and appears in the photos taken on a trekking expedition. Brunaldo (Facebook name; unconfirmed) was previously part of the young bonehead scene in Paris, in the circle around Serge Ayoub of Troisième Voie and the Jeunesses nationalistes révolutionnaires (JNR). Jean was close to Samuel Dufour, a neo-Nazi bonehead who, with Esteban Morrilo, was involved in the murder of Clément Méric, on June 5, 2013, in Paris. He currently seems to be part of the close-knit Atalante inner circle. Chloé Fleury is his partner.     |

| Chloé Fleury, aka Lucy Mergnac [French expat, not very active] Present at a hiking outing with other Atalante militants and has participated in postering in Montréal. Jean Brunaldo is her partner.   |

| Francis Hamelin [not very active] Catholic fundamentalist bonehead and raving neo-Nazi. Former member of Troisième Voie Québec who has been seen at Atalante actions in Montréal.  |

| Rémi Chabot [not very active] Old bonehead who assaulted a Haitian worker in 2002, and who remains part of the current ultranationalist milieu and part of Atalante’s entourage.   |

| Félix-Olivier Beauchamp Originally from Mont-Laurier, he has participated in a number of Atalante actions since the group’s founding, both in Montréal and in Québec City.    |

| Éric Gervais Lives in St-Eustache, father of two children. He started his career as a bonehead with Coup de Masse and is still present at most Légitime Violence concerts today.  |

| Jonathan Côté Old bonehead, former member of the Berzerker Boot Boys. He is a longstanding member of the Légitime Violence scene. It was through their contact with him and a few of his old neo-Nazi friends that the Québec Stompers found their way to the far right.Julie Laurier Has been part of the Légitime Violence entourage for years. She is Jonathan Côté’s partner.   |

| Mickaël Delaunay An employee of Vinland Productions, Delauney denies being a member of Atalante, but a recent VICE report has him participating a number of the group’s actions.  |

| Yannick Gasser Lives in Terrebonne. Not very politically active. A fan of Légitime Violence who has been pulled to the right by the band’s entourage. He participated in the homage to Jeanne d’Arc organized by Atalante in May 7, 2018.   |

| Ian Alarie [aka Ian Enforme] A neo-Nazi fan of NSBM, close to the Soldiers of Odin. He lives in the Montréal area, possibly Varennes. He took part is a few Atalante Montréal actions, as well as in the Atalante Québec march.     |

| Martin Léger Previously known by the sobriquet “Cad Stomper,” Léger is far from being an Atalante militant. In fact, the vigour with which he distances himself from the Stompers has led Légitime Violence to dedicate the song Sale traître [Dirty Traitor] to him. That said, we think that Léger warrants a mention, because he manages an armory and a gun range in the Québec City area and made headlines in 2017, when he was associated with a planned pro-gun demonstration at the memorial for the victims of the anti-feminist December 6, 1989, Polytechnique massacre, and released a misogynist video when the demonstration was greeted with intense criticism.   |

| Steve Lavallée An old bonehead, former member of the Berzerker Boot Boys. He is a longstanding member of the Légitime Violence scene. He has developed a passion for “live action role playing” (LARP), and joins other neo-Nazis in the Vinland Viking activities.   |

| Dominic Gendron Longstanding member of the Québec Stompers, he has been exiled to Abitibi for a few years. He nonetheless continued to support the band as well as he could. He participated in some Atalante actions when he was available.    |

| Jonathan Croteau Fan of Légitime Violence who has long been part of the Québec Stompers scene. Among other things, he is alleged to have participated in the New Year’s Eve 2007 attack on the bar AgitéE.  |

| Sébastien Théberge [close to Légitime Violence] Very close to Légitime Violence and an Atalante supporter. Lives in Montmagny. Former member of the Soldiers of Odin, he was present at the Atalante gathering in April 2018 to commemorate a hundred years since the conscription crisis.  |

| Evymay Lacroix Fan of Légitime Violence and into power lifting. Also an aficionado of NSBM and an open neo-Nazi.   |

Québec Stompers: Raphaël Lévesque, Jonathan Payeur, Olivier Gadoury, Benjamin Bastien, Yan Barras and Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau.

Québec Stompers: Roxane Baron, Jonathan Payeur, Étienne Mailhot-Breuneau, Benjamin Bastien, Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau and Raphaël Lévesque. Below, on the left, Jonathan Côté.

Québec Stompers: Valéry Lévesque, Roxane Baron, Yannick Vézina, Antoine Mailhot-Bruneau and Jonathan Payeur.

[i] Atalante militants previously used the same theatrics to intimidate a reporter from CBC News and Ian Bussières from the Soleil. For more information, see “Atalante et le harcèlement des médias.” They also engaged in a certain amount of tweaksome shit directed at La Presse journalist Philippe Tesceira-Lessard, who has published a series of articles about Légitime Violence, bringing to light the criminal histories of our little friends, and on active members of the Canadian Armed Forces among their symathizers.

[ii] Oï is a punk rock subgenre that was initially meant to draw different British working-class subcultures into a unified movement, but which was later hijacked by racist elements in the scene, with the goal of recruiting disillusioned proletarian youth into fascist political movements like the National Front and the British National Party.

[iii] RAC, or “Rock Against Communism,” is a neofascist movement created in the 1980s in reaction to “Rock Against Racism,” a movement formed by left-wing artists and musicians to combat the infiltration of racist elements into the countercultural scene, particularly the skinhead scene. The flagship RAC group is Skrewdriver, with its spiritual leader Ian Stuart, the group’s singer and the founder of the white power federation Blood & Honour.

[iv] The term “boneheads” designates racist and white supremacist skinheads, as opposed to the generic term “skinhead,” which designates members of the traditional skinhead counterculture, which, historically, was an inclusive and antiracist scene.

[v] For more information, see Xavier Camus, “Québec et l’extrême droite italienne.”

[vi] The eponymous song, Légitime Violence , 2010.

[vii] “Un amour perdu,” from the album Nouvelle France Skinhead, 2011.

[viii] The tattoos and inscriptions reading NFSH favoured by Légitime Violence and its fans signify “Nouvelle France Skinhead,” which is also the title of Légitime Violence’s first album, released in 2011.

[ix] The « nationaliste révolutionnaire » tendency is a branch of Third Position fascism. National-revolutionary and Third Position ideology are part of a political tendency that has existed since at least the 1960s, with many points of reference in the fascist movement stretching back to the “Strasserite” tendency in the Nazi Party. The term “Third Position” designates different far-right and neofascist currents characterized by the simultaneous rejection of capitalism and communism and favours an identitarian ultranationalism based on a confused mix of far-left (socialist) and far-right (nationalist) theories. Internationally, the Third Position is currently the dominant tendency within the fascist and revolutionary far right. The anticapitalism of most national revolutionaries is located in an antisemitic framework.

[x] The term “globalist,” like the recurrent references to the the secret hand of George Soros, is generally recognized as euphemistic code for the alleged international Jewish conspiracy, which is itself an echo of various nineteenth-century antisemitic conspiracy theories.

[xi] A leading opponent of the Vatican II reforms, Mgr Marcel Lefebvre founded the Fraternité Saint-Pie-X (FSSPX) in 1970 and established a seminary in the Swiss village of Écône. In 1975, Lefebvre received a Vatican order to dissolve the society, which he ignored. In 1988, in spite of a specific ban pronounced by Pope John Paul II, he consecrated four bishops, authorizing them to carry out the FSSPX’s work, which led to his immediate excommunication and the excommunication of the bishops who participated in the ceremony. Lefebvre, who died three years later, consistently refused to recognize his excommunication.

Lefebvre was suported by far-right movements the world over, including Blas Piñar’s Fuerza Nueva, in Spain, the Movimiento sociale italiano, and the Front national, in France. He regularly expressed vitriolic racism, striking out at Jews and Muslims, and was a fierce opponent of the ecumenical dialogue with other traditions advanced by the pope. In Québec, the Lefebvrists claimed the government was controlled by communists.

The FSSPX welcomes with open arms Catholics who oppose multiculturalism, democracy, and freedom of conscience and is outraged that the Church has abandoned its struggle against these various scourges. As Lefebvre put it: “[T]he union that liberal Catholics want between the Church and revolution is an adulterous union! Such an adulterous union can only produce bastards. . . .It’s the same with the Free Masons. . . . You don’t engage in dialogue with communists. . . . We cannot accept such a dialogue! You don’t engage in a dialogue with the devil.”

In Québec, the FSSPX has served as a spiritual refuge for the far right since the 1980s, when a number of members of the Cercle Jeune nation were active within the sect.

[xii] Dupuis was included in a recent news report by Radio-Canada on the Sainte-Famille private school, which is run by the FSSPX.

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

Citizenship can only exist and be valued if there is also a category of others, those without status. For this distinction to exist, it must be enforced by the state, which has a number of tools to do so.

Deportation is one such tool. Deportation is a violent process in which the state removes all agency from an individual in order to exclude them from the territory over which it asserts its authority. To accomplish this task, the state uses different tactics, one of which is detention centers or migrant prisons. Migrant prisons are used as holding centers prior to deportation. People without status can be arrested and imprisoned while they wait to be flown out of the country, sometimes to far-away lands that they have no relationship to.

The state has been deporting more people in recent years and is currently expanding its capacity to do so. Hiring more Canadian Border Service Agency (CBSA) personnel, finding various ways to monitor undocumented folks, and building new detention centers are ways the state is increasing its ability to effectively deport people. In Laval, a city on Montreal’s north shore, the government wants to build a so-called “more humane” detention center next to a detention center that already exists. However, we all know that a golden cage is still a cage. This is a provocation, a confrontational act, an attack on undocumented folks, on our communities, on all of us. The current migrant crisis will only intensify, considering climate change, war, and widespread conflict in many countries. Migrants risk brutal rejection from the western world, which scrambles to reinforce its borders against the others, the barbarian enemy invasion. The media has recently said that the federal government wants to increase the number of annual deportations by 30%. A project of domination like the migrant prison brings the state of Canada closer to achieving its colonial mission of controlling every aspect of people’s lives and the land it is situated on. By reinforcing its own legitimacy and the category of others, the fascistic ideal of “purity” seems ever more possible.

It’s important to note that the authors of this text are white and were born in Canada. That being said, we are not threatened by deportation, or being locked up in the migrant prison. We still choose to struggle against the construction of this new prison in solidarity with those who risk their lives looking for a better life elsewhere. Not only are we against the policing of non-status people and detention centers, but our objective is also to destroy domination in all its forms, including states and borders. Even though we have the privilege of having citizenship, we are not proud Canadians. We have no feelings of belonging to the national identity. The struggle we want to build doesn’t hope to be recognized by the state or get its approval. Instead of asking the government to stop deportations, we choose to subvert our privilege. We have the ability to opt into struggle and throw a wrench into the gears of the deportation machine. Those responsible for detention should sleep with one eye open.

We want to try to coordinate our energy in an informal and decentralized way to focus on stopping the construction of the migrant prison. If we focus on this specific struggle, it’s in order to obtain effective results. This prison is one of many tools in the state’s arsenal, an important aspect in the preservation of Canada and its borders. That being said, we are opposed to all prisons, all forms of detention, though this time we choose to focus on this particular element. We hope that others will contribute in multiplying offensive endeavors that cause tension to rise. That being said, we refuse to wait for mass participation to act. The time is now.

What can it look like to fight the state and its projects? There is no single answer to this question and no magic formula for success. However, there are certain principles that can help us make coherent choices and can prevent eventual recuperation by politicians and the Left. For us, these principles are applicable to all of our struggles. Some of them, such as the golden no snitching rule, are more obvious. But let’s dig a little deeper.

First, we refuse to make demands to the state. Making demands is often a reflex for people who struggle against specific projects. Demands put forward a narrative in which only those who exert power over others –those in positions of authority-can create change. This reflex is a negation of our own agency and our capacity to act in the world by delegating our power to politicians and bosses. We want to move away from this method of organizing and towards a struggle that can subvert power dynamics and create change without waiting for permission. We want to destroy the state, not reinforce its legitimacy.

Negotiation can also be tempting when we don’t think we have the power to create change. Liberals would want us to believe that we always have to make concessions, to give in a little. However, in a situation like this one, no alternative is acceptable. No nicer prisons, no friendlier CBSA agents, and no alternative monitoring or policing of undocumented communities should be tolerated.

An alternative to demands and negotiation is direct confrontation. We think that attacks are an integral part of preventing the construction of this migrant prison. Attacking those who want to build the prison, those who are drawing up the plans, those who are pouring the cement, those who are intending to lock people up. Forms of attacks can vary according to people’s abilities, trust, etc.

Direct confrontation does not require centralization or hierarchy. In fact, we think that it is necessary to organize in a decentralized and informal way. This means no formal identity, no membership, no orders. People should organize themselves with individuals they share affinity with, meaning ideas, practice, and trust.

Using these methods, we see a way to better adapt to contexts and the relationships between those who struggle. Informal organizing prioritizes the content rather than container. Not waiting for a party, committee, or group’s approval allows our interventions to be more effective. For trust to be established among those who struggle, a certain level of engagement is necessary. There is a difference between personal engagement and formal organizing in terms of accountability. In the first, one is accountable to their ideas, in the second, they are accountable to a formality that is bigger than them in which the organization becomes more important than relationships and individual analysis. To meet periodically in larger numbers to share information and perspectives without making centralized decisions is desirable to us. We recognize the tendency that people have to engage in a variety of struggles, without continuity, with actions that remain symbolic insofar as they have minimal impact on their targets. This kind of involvement tends to prevent expansive conflictuality. The importance of identifying and targeting those responsible (and their collaborators) for domination and detention, and to share analysis regarding medium to long term perspectives is clear. However, all of these energies must remain in motion and should not be trapped in formal organizations under the pretext of maintaining better continuity.

To create a larger context for struggle, several individuals, identifying as anarchists, revolutionaries, or other “autonomous forces”, have a tendency to fall in the trap of the masses and public opinion by organizing alongside the Left and by communicating with mass media. But at what price? It is already obvious that all reforms, as socializing as they may be, contribute to strengthening the chains that bind us to the state. We want to use our own means (zines, independent media, posters, graffiti, infrastructure that supports undocumented people) and build the basis for our struggles according to our anarchist principles that are in rupture with institutions. To subvert social dynamics and destroy domination, we refuse to follow leftist movements and organizing.

Realistically, the only way that we can stop Canada’s deportations and new prisons, its exploitation, domination, and support for the worst kinds of atrocities, its propagation of authoritarian, racist, and colonial endeavors, is to destroy the colonial project altogether. The state needs to be confronted with insurrection, the sabotage of its structures, and permanent revolt. Cracks are everywhere – let’s find them.

From the No Borders Media Network

Montreal, December 10th – Protesters are currently blocking all the main entrances to the main Canada Post International Mail Processing Center near Montreal’s Trudeau International Airport (at 555 McArthur in Ville St-Laurent). At present, dozens of trucks are backed up at the main entrances, where three groups of protesters are using banners to block entrances. No trucks are able to leave the facility.

The direct action is in support of postal workers, and in opposition to the repressive ‘back-to-work’ legislation passed by the Canadian government on November 26, 2018. The anti-worker law effectively prevents the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW) from continuing their strike.

Today’s protest is the first direct action in support of postal workers in Quebec since the “back-to-work” law passed, joining protests that have already happened across Canada, including in Halifax, Sydney, Fredericton, Ottawa, Kingston, Toronto, Hamilton,Edmonton, Whitehorse and Vancouver. Recently, picketers were arrested in both Halifax and Ottawa for their blockades. Comrades in Montreal were expressing solidarity with similar pickets and blockades that have happened elsewhere, including for arrested protesters.

Today’s action is organized by IWW Montreal, with the support of retired postal workers and community members. The public press release for the action is available here: www.facebook.com/…/phot…/a.1521183491427251/2263430937202499 (check the Iww Montréal facebook page for more updates).

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, tens of thousands of black slaves escaped from American plantations and headed north in search of liberation. Many crossed into Canada, where slavery had been formally abolished in 1834. They settled throughout the eastern provinces – in Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia – forming small, tight-knit communities in urban centres.

These newly landed black migrants were generally met with racist attitudes from white society. Although segregation was never enshrined into Canadian law, they were denied jobs, housing, and access to government services. As the state dreamed its public education system into existence, black children found themselves crammed into segregated and inferior schools. Whites-only establishments were common throughout, with hotels, restaurants, and hospitals refusing service to black patrons.

In response, black communities began to form their own social organizations. In Montreal, numerous community centres were founded to combat social exclusion: the Women’s Coloured Club in 1902, the Union United Congregational Church in 1907, and the Negro Community Centre in 1927. They provided free schooling and healthcare, and distributed food and other resources.

Around the same time, racist groups sought to gain a foothold in the Canadian political sphere by establishing themselves in a number of cities. Montreal saw its own chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, although its power failed to materialize in any significant way. The Klan was briefly popular in Saskachetwan, with a membership of 25,000 that helped James Anderson defeat the Liberal party in the 1929 provincial election.

The black population in Montreal would not see significant growth until federal restrictions on immigration were lifted in the early 1960’s. Between 1961 and 1968, the black population grew from 7,000 to 50,000. This period of influx saw a proliferation of anti-racist, anti-colonial ideas from the US, Africa, and the Caribbean. Black intellectuals drew from the analyses on race and imperialism formulated by members of the Black Power movement and the various movements for independence throughout Africa. They organized conferences throughout the city, echoing the principles of black revolutionary thought: autonomy, self-sufficiency, and defence.

Many young black migrants enrolled at Sir George Williams University (SGW), which offered night classes and a relaxed admissions policy. The university’s heterogeneous population stood in juxtaposition to McGill’s largely white, upper-class student body. Despite its reputation as one of the more inclusive and progressive universities in the country, racism from students and administration was not uncommon at SGW.

In May 1968, six Black Caribbean students submitted a formal complaint against biology professor Perry Anderson. They accused Anderson of discriminating against black students in his class, giving them lower grades for doing the same quality of work as their white counterparts. But after months of inaction, the students became dissatisfied with how their complaint was being handled. They decided to make the issue public, and began organizing sit-ins and distributing leaflets about their situation. In turn, the university established a hearing committee that would vote on the best way to resolve the conflict.

Multiple hearings and assemblies were held throughout January 1969. Professors and other faculty members defended Anderson, while students of colour shared their own experiences of discrimination on campus. Many speakers echoed the words of the Black Panther Party, which had been gaining prominence south of the border. They called for students to be wary of the administration and take matters into their own hands.

On January 29, 200 students walked out of a hearing in protest. They saw the process as a way for the administration to push for Anderson’s innocence and wring their hands of any wrongdoing. After almost 10 months since the original complaint had been lodged, they saw the problem not simply as the prejudices of a particular professor, but the systemic racism found throughout many aspects of the university.

Students set up an occupation of the school’s computer lab on the 9th floor of the Henry F. Hall Building. Nine days later, the occupation spread to the faculty lounge on the 7th floor. On February 10th, the students proposed an end to the protest if the university established another hearing committee and disregarded the classes that had been missed by participants in the occupation. The university also promised to not file charges or pursue police involvement.

With less than a hundred people remaining in the building, riot police began to amass on nearby streets. The university had seemingly gone back on their promise. In response, the students barricaded the stairwells and shut off the elevator system. With cops racing up the stairs, the students chose to use what little leverage they had left, threatening to destroy the millions of dollars of computer equipment if they were not let out safely.

Despite their efforts, the eviction was underway. Students began smashing equipment and throwing thousands of computer cards out of the windows. As police assembled on the 9th floor, a fire broke out on the floor directly underneath. Meanwhile, a white mob that had materialized outside chanted “Let the niggers burn!” Students now attempted to escape by disassembling the barricades, but found that the room’s fire extinguisher and axe were missing. They had been confiscated by cops the day prior.

The protest ended with 97 arrests and approximately $2 million in damages. Anderson, who had been suspended during the crisis, was reinstated on February 12. On June 30, the hearing committee reported “there was nothing in the evidence to substantiate a general charge of racism” and found him not guilty.

This story is a bit different than the “official version.” A quick Google search will turn up dozens of articles about the Computer Riot, almost all of which retell the narrative given by the university. According to them, police were only called to evict the occupation once students had begun barricading the stairwells. This is a classic tactic used to legitimize heavy-handed policing of direct action, claiming that certain control tactics were necessary to pacify a “rowdy” crowd.

Secondly, it’s often claimed that protesters started the fire that caused considerable damage to the building, while the students themselves attest that it was the work of the police. This has most recently been touched upon in the documentary film Ninth Floor.

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

Here’s a simple way to complicate the lives of Gardas and other security guards.

During their night rounds, security guards are equipped with a scanner to ensure they complete a number of tasks. They have to scan barcodes, QR codes and magnetic chips to prove to their superiors that they’ve done their rounds.

You’ll find these codes on exit doors, in bathrooms, some classrooms, at the ends of hallways and other places.

These images come from UQAM, but there are certainly some in your institutions, schools or not!

You can do your own rounds, to complicate theirs!

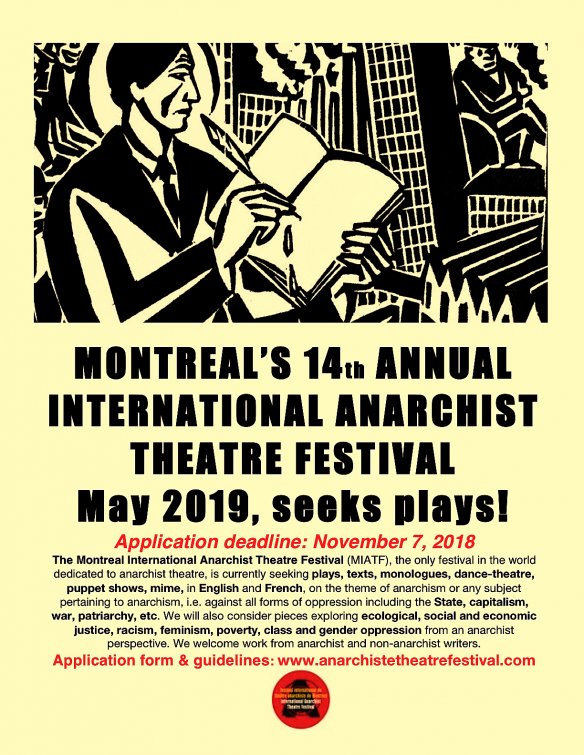

From The Montreal International Anarchist Theatre Festival

The Montreal International Anarchist Theatre Festival (MIATF), the only festival in the world dedicated to anarchist theatre, is looking for plays, texts, monologues, dance-theatre, puppet shows, mime, in English and French, on the theme of anarchism or any subject pertaining to anarchism, i.e. against all forms of oppression including the State, capitalism, war, capitalism, patriarchy, etc. We will also consider pieces exploring ecological, social and economic justice, racism, feminism, poverty, class and gender oppression from an anarchist perspective. We welcome work from anarchist and non-anarchist writers.

The 2019 edition of the festival will take place on May 22-23. Are you interested in presenting your work during the festival? Send us the application form by November 7, 2018!

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info