From Stop the Prison

When is the Laval Immigration Detention Centre slated to be built?

The prison is supposed to be operational in 2021, though no official timeline has been made public.

Where will the prison be built?

The site for the prison is an approximately 23,700 square metre piece of land directly beside Leclerc prison, on Correctional Service of Canada grounds in Laval. The CBSA was reluctant to select this plot of land, noting that “the close proximity of the site to the existing high security institution is not ideal as IHC [Immigration Holding Centre: their euphemism for the prison] should not be perceived to be associated with a correctional institution.” This site was officially chosen in February 2017.

The settler-colonial states (Canada and Quebec, respectively) within whose borders the prison will be built are founded on the violent colonization and dispossession of Indigenous peoples and lands. Specifically, Leclerc is located on Kanien’keha:ka and Algonquin territory. Settler governance relies on both the illegitimate claim to these territories and the material basis of their control, enforced by the various arms of the carceral state: from detaining and deporting migrants to policing Indigenous communities. Supporting the project of Indigenous sovereignty means rejecting the legitimacy of Canadian and Quebecois settler governance, including the defining and policing of state borders.

How many people will the prison hold?

According to the government’s contract, the proposed prison will have the capacity to hold 133 migrants at one time (with an additional 25 overflow cots, bringing the total capacity to 158). This would increase the current maximum holding capacity of 144.

Who will be detained in this new prison?

Hundreds of thousands of people live in Canada without status, embedded in communities, families, and friendships. Every year close to ten thousand people are ripped away from these relationships, returned to situations that are violent or dangerous, to places they do not know, or where they have no opportunities to support themselves.

Under Canadian law, the CBSA can arrest and detain migrants – both those who are here without permission of the Canadian state and permanent residents – who are suspected of being a “threat” to public safety, who are deemed likely to skip upcoming hearings, or whose identity is in question. These migrants – and often their children – are taken to the CBSA-run prisons in Laval or Toronto, to the CBSA’s temporary detention centre in the Vancouver airport, or to maximum-security wings of provincial jails. Under current policy, there are no guidelines around whether or not children will be imprisoned along with their parents, and detention can be indefinite.

In reality, Canada’s immigration system makes it virtually impossible for all but the most privileged or affluent of migrants to obtain legal status to live and work here permanently. Migrants deemed a “threat” or at risk of non-compliance at the whims of the CBSA are often those with family ties in Canada, insufficient funds to leave, those facing violence if they are deported, or those with active social campaigns against their deportation. The risk of imprisonment is used to discipline all migrants, an instrument of coercion that normalizes other forms of control such as the human and electronic monitoring systems proposed as “improved” alternatives by the Liberal government. But the “choice” to comply and avoid incarceration is ultimately a false one, in which the end result is still likely deportation.

In a context where over 25,000 people have walked across the border from the US since 2016, in which the vast majority of these migrants are likely to be refused refugee status and will soon be facing deportation, and in which the racist and Islamophobic far-right is stoking anti-immigrant sentiments, we must understand the new migrant prison as part of a strategy of the Canadian state to heighten its repressive control over freedom of movement.

Despite the photo-ops and press releases on the state’s refugee resettlement efforts, Canada is far from a benevolent bystander; the Canadian state creates and exacerbates the conditions that force people to leave their homes. From imperialist wars to an economy massively reliant on colonial resource extraction both here and abroad. Trudeau’s recent purchase of the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline indicates a future in which increased emissions will create new waves of climate refugees. From Canadian mining projects in Latin America to the outsourced production of cheap goods for Canadian markets, Canadian state and capitalist interests export the burden of production, and police the movements of those who inherit the costs. The proposed migrant prison is simply one piece of this international architecture, and the people who would be detained within it are simply a few of the many people dispossessed by the Canadian state and other imperialist powers.

Who is involved in the construction of the prison?

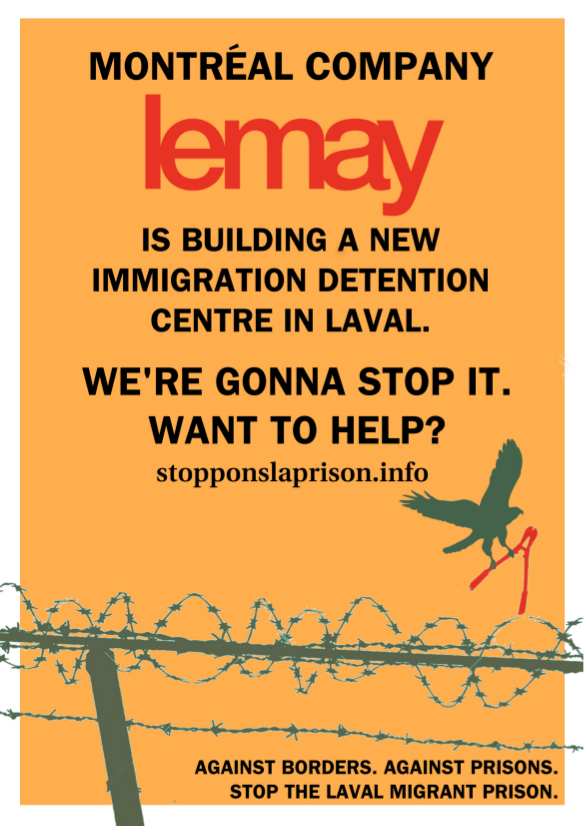

So far, two companies have been awarded contracts for the construction of this project: Lemay, an architecture firm based in Montréal and Groupe A, another architecture firm based in Québec City. For more information on these companies, see the “Companies” page. In the coming months we can expect to learn about more companies and contractors that will be involved in this project in various capacities.

Who is funding the construction of the project?

The federal government announced a new investment of $138 million into immigrant detention in 2016, of which $122 million is going towards the construction of two new prisons. One in Laval, Quebec and one in Surrey, British Columbia. To date, over $5 million in contracts have been awarded to Lemay and Groupe A towards the design of this prison in Laval.

Why should we oppose the construction of improved prison facilities?

From the beginning, the government has moved to position this project as an improvement: from the choice of a ‘socially and environmentally sustainable’ firm as the principal architect, to the emphasis on the “non-institutional” design of the centre and “alternatives” to detention. But the veneer of social responsibility doesn’t change the violence of prisons and deportation: there’s no such thing as a nice prison.

The contract for the prison seems more invested in concealing its carceral nature from those outside than creating a more habitable environment for those imprisoned within. Preliminary specs suggest that “fencing should be aesthetically covered by foliage or other materials to limit harshness of look and detract from overt identification of fence.” Iron bars over windows must “be as inconspicuous as possible to the outside public” while nevertheless maintaining their functionality. The one meter high fence surrounding the children’s yard is stressed to be “similar to a daycare setting”, though a six-foot high “visual barrier” must be built to prevent others from being able to see in, and children from being able to see out.

Regardless of aesthetics or energy-efficiency, a prison is a still a fortified building that people can’t leave, that separates those inside from community, loved ones and adequate health care, and that subjects prisoners to extreme psychological distress. Since 2000, at least sixteen people have died in immigration detention while in CBSA custody. The CBSA’s superficial response to the outcry over these deaths is evident in the project specs, which simply require that architecture should limit opportunities for self-harm, while unavoidably reproducing the inherent immiseration of incarceration.

Even for those spared the experience of pre-deportation incarceration, the threat of prison remains, compelling migrants to accept other kinds of repressive conditions. These institutions also normalize the legitimacy of the Canadian state to police who moves and stays within the territories it occupies.

Indeed, any account of the settler state’s control of territory should begin with the ongoing colonial occupation of Indigenous lands, on whose traditional territories the prison is intended to be built. Advancing Indigenous sovereignty requires challenging the legitimacy of Canadian and Quebecois settler governance, including the creation and enforcement of borders. The same colonial and imperial relationships that displace migrants elsewhere in the world are the very basis of the existence of the Canadian settler state.

The struggle to block construction of the Laval Migrant Detention Centre is thus embedded in broader struggles against colonialism and imperialism. It is part of a struggle to abolish all prisons and tear down every colonial border. We don’t just want to stop this prison, but close all those already in existence.

Isn’t the government turning towards funding alternatives to imprisonment and detention?

Of the $138 million dollars the Liberal government has allocated towards “immigration reform”, only $5 million are earmarked for “alternatives” to detention. What are these “alternatives”? They include “human and electronic monitoring systems” like bonds, electronic bracelets, and electronic reporting systems. These reporting systems are themselves another form of detention — for instance, practices like reporting twice a week often prevent migrants from holding stable jobs. These “alternatives” also include arrangements which put NGOs in charge of “community supervision”. While the Canadian government looks to cut costs by delegating the policing of migrants to invasive technology and complicit non-profits, the majority of their “new and improved” immigration plan still centers on detention, through the construction of two new prisons in Laval and Surrey.

In some respects, the alternatives proposed are preferable to prison. But, they are far from “humane”. On the one hand, the threat of indefinite incarceration in one of the CBSA’s prisons justifies increasingly invasive control mechanisms outside of the prison – as though anything short of imprisonment is an act of compassion. On the other hand, these “alternatives” normalize the continued brutality of imprisonment as a form of punishment for those unable or unwilling to comply with the conditions of state control. Either way, both prison and “alternatives” end in deportation, while one actual alternative to deportation – a pathway to regularized status for all – remains unattainable.

Isn’t Montreal a sanctuary city?

In February 2017, Montreal declared itself a “Sanctuary City”. Unfortunately, this declaration has turned out to be little more than empty words. The SPVM continues to actively colloborate with the CBSA, meaning that even routine traffic stops could result in CBSA intervention, and undocumented migrants are offered little respite from the threat of detention and deportation. In fact, since the Sanctuary City declaration, SPVM calls to CBSA have increased, making Montréal the Canadian city with the highest rate of contact between local police and the CBSA. In March 2018, CBSA agents violently arrested Lucy Francineth Granados at her home in Montréal. Lucy was subsequently deported from a city whose new ‘progressive’ administration had campaigned on the promise to implement a “real” sanctuary city.

How can the construction of this prison be stopped?

To stop the construction of this prison, we’re going to need a multifaceted struggle. We’ll need concerted research efforts, public information campaigns, broad-based mobiizations, direct disruptions of supply chains and construction sites, and whatever it takes to make construction of this project impossible.

To do this we need to think strategically about which pressure points we can target and leverage, and how to build alliances with related movements against prisons, borders, and white supremacy; no struggle exists in isolation. From flyering your neighbours to organizing demonstrations and actions in opposition, there are endless ways for people to autonomously organize against this project.

The Materials page of stopponslaprison.info contains some resources for those looking for a place to start.

Where can I learn more about this project?

Stopponslaprison.info is an information clearinghouse for news, analysis, and materials related to the struggle against the Laval Immigration Detention Centre. You can download and consult the documents and research related to this project on the Documents sub-page.

In 2016 the federal government announced the construction of a new migrant detention center in Laval. This prison, which is anticipated to hold up to 158 undocumented migrants, is intended to be built on Correctional Service of Canada grounds, right beside Leclerc prison, and is slated to open in 2021. While the Liberal government is attempting to spin this project as a more humane way to detain migrants, we call it what it is — a prison, and know that this is simply prettier window dressing on a violent system of imprisonment and deportation, one that keeps people locked in cages while tearing apart families and communities. We want a world without prisons or colonial borders, a world where people, not states, can decide how they can move and where they can stay. Stopping the construction of the Laval Immigration Detention Centre is one step in the struggle to tear down migrant prisons everywhere.

In 2016 the federal government announced the construction of a new migrant detention center in Laval. This prison, which is anticipated to hold up to 158 undocumented migrants, is intended to be built on Correctional Service of Canada grounds, right beside Leclerc prison, and is slated to open in 2021. While the Liberal government is attempting to spin this project as a more humane way to detain migrants, we call it what it is — a prison, and know that this is simply prettier window dressing on a violent system of imprisonment and deportation, one that keeps people locked in cages while tearing apart families and communities. We want a world without prisons or colonial borders, a world where people, not states, can decide how they can move and where they can stay. Stopping the construction of the Laval Immigration Detention Centre is one step in the struggle to tear down migrant prisons everywhere.