From It’s Going Down

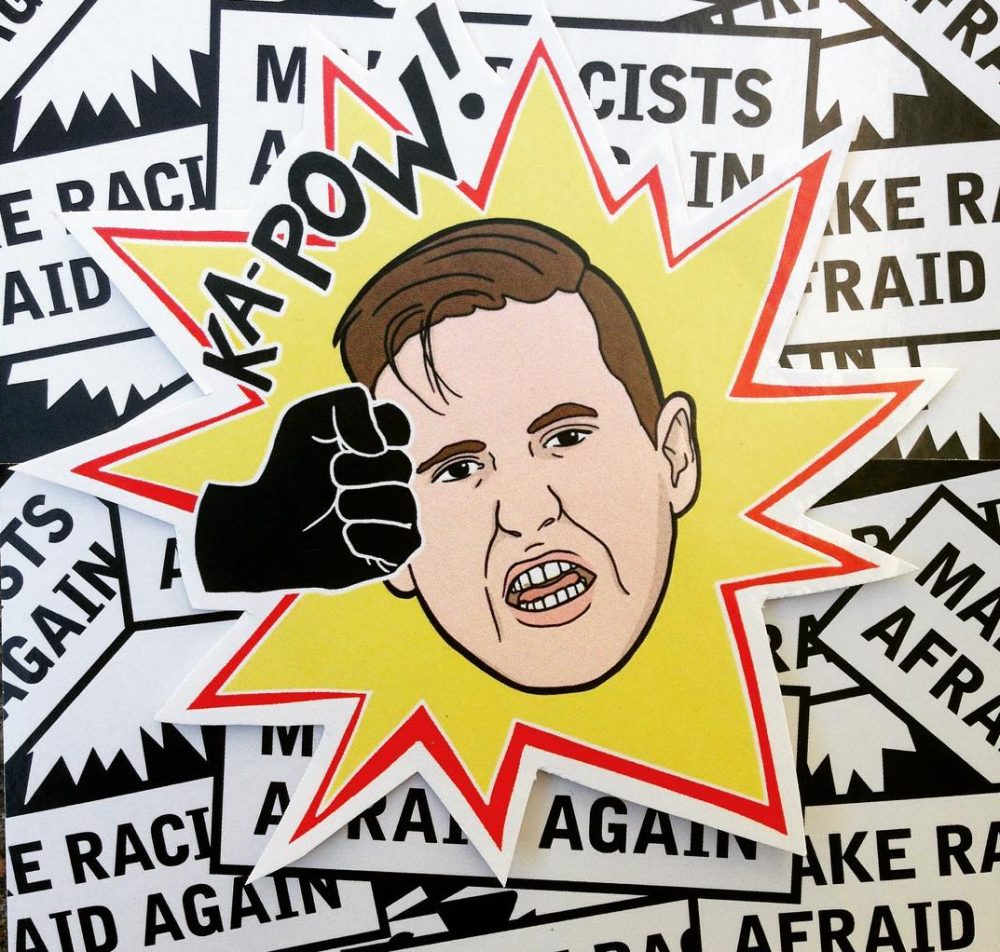

Few street artists have captured the sights, feels, and emotions of combative social movements as well as Zola, an anarchist based in so-called Montreal. Bringing to the streets high color posters, stickers, and artwork that reflects anarchist, antifascist, and anti-pipeline battles – among others, their work has become a staple in the area as well as synonymous with the growing anarchist movement in the city. Wanting to know more about Zola, their work, and what drives them, we caught up with them to find out more about the artist behind the posters.

IGD: How did you get interested in street art and graffiti? Was it before you became an anarchist?

I was around anarchist circles way before I started to be active in street art, but I had also already been looking into street art websites and owned a few street art books for a long while. It might be lame to say so today, but Banksy was definitely a big inspiration back then. Like many others, he introduced me to all the possibilities street art could offer in terms of anti-capitalist discourse.

For me, the merging of street art and anarchist activism really took off around the Occupy movement. Back then I was interested in the subversiveness of feminist and femme mediums like textile and yarn-bombing clashing with the mostly very masculine world of graffiti and privatized public spaces. With my collective during those 2011-2013 years, we experimented a lot in form while I solidified my radical discourse.

That’s also the period I realized that anarchists and radical politics people could be very easily suspicious or hateful towards experimentation and art, and navigating between different scenes like this could be socially costly on both sides. That period really created the experience and the activist art network to base off the wheatpaste practice I have now.

IGD: What was your process of radicalization?

I think like most, I radicalized the moment I physically realized the system was there to maintain oppression instead of peace. The student movement here has always had it rough with police repression, and being chased off by someone paid by the state with a fucking shield and stick to beat you up has got to radicalize you pretty fast. This gave me the will to reach for anti-oppressive politics in social movements and make friends with folks with very diverse life backgrounds and experience of racial, environmental and other forms of state violence.

IGD: There’s so much talk of graffiti vs street art, and vice versa. What is your take? Why do you choose to work often with posters and wheatpaste?

Wheatpasting really works for me because I can take the time to prepare something I am aesthetically satisfied with in the safety of my home, and then install it outside in an instant. I never had the opportunity or guts to practice and learn can control or draw freehand.

In terms of scenes or cultures, I guess I have a love/hate relationship with both graffiti and street art. I think there’s a lot of idiots and haters out there, but also a lot of good folks doing the good work in both mediums. Obviously what makes it complicated nowadays is the monetization of those cultures and how capitalism slowly creeps into every artist’s mind.

IGD: What motivates you to present the images and characters that you do?

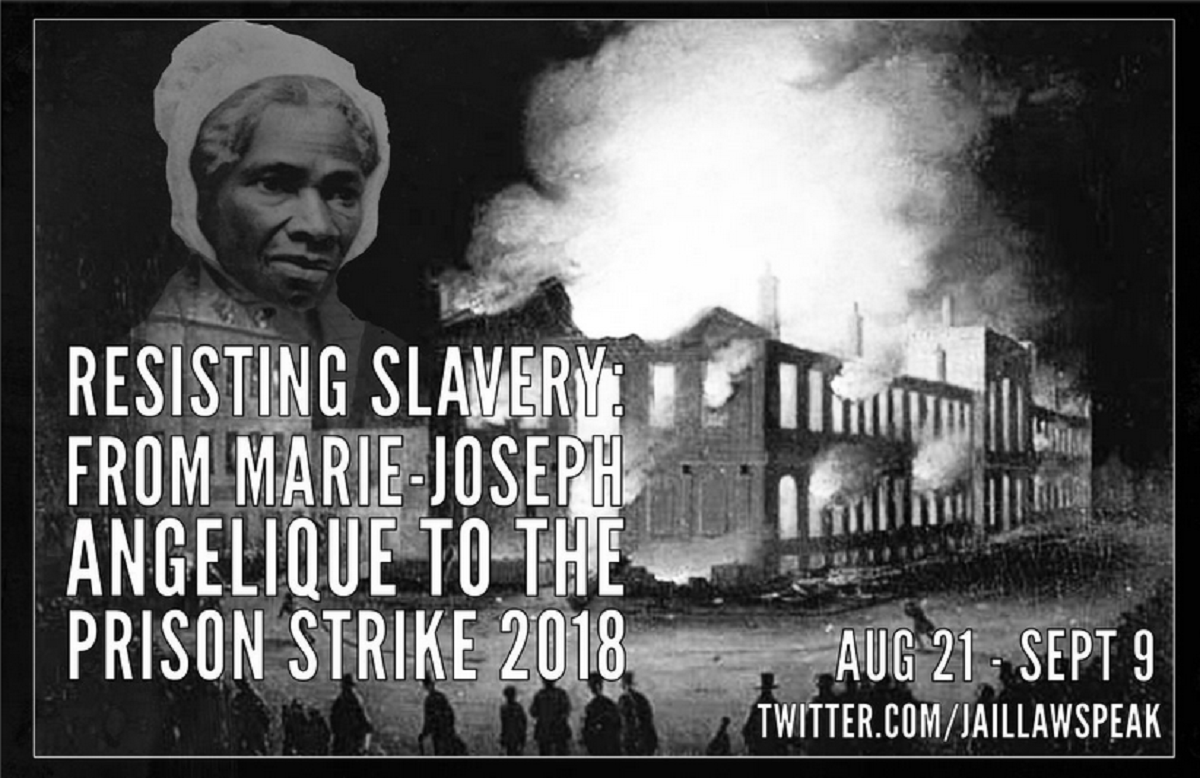

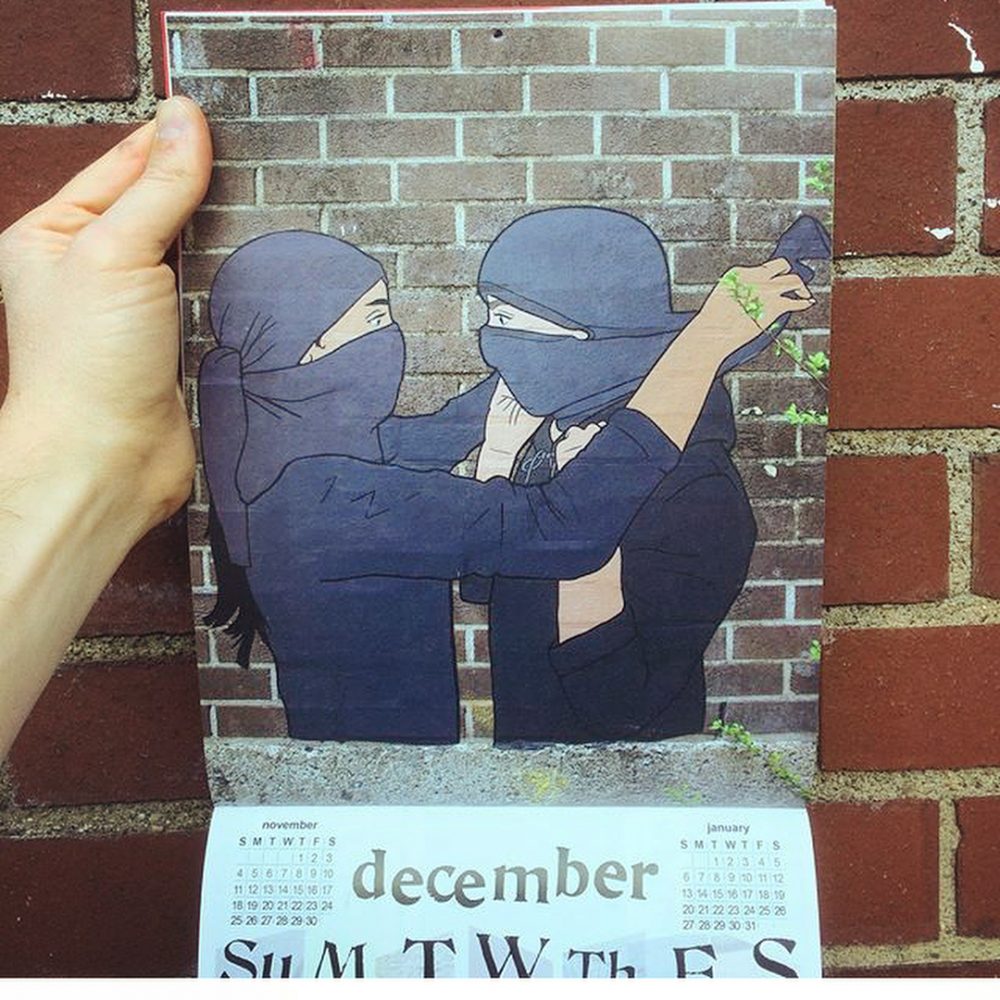

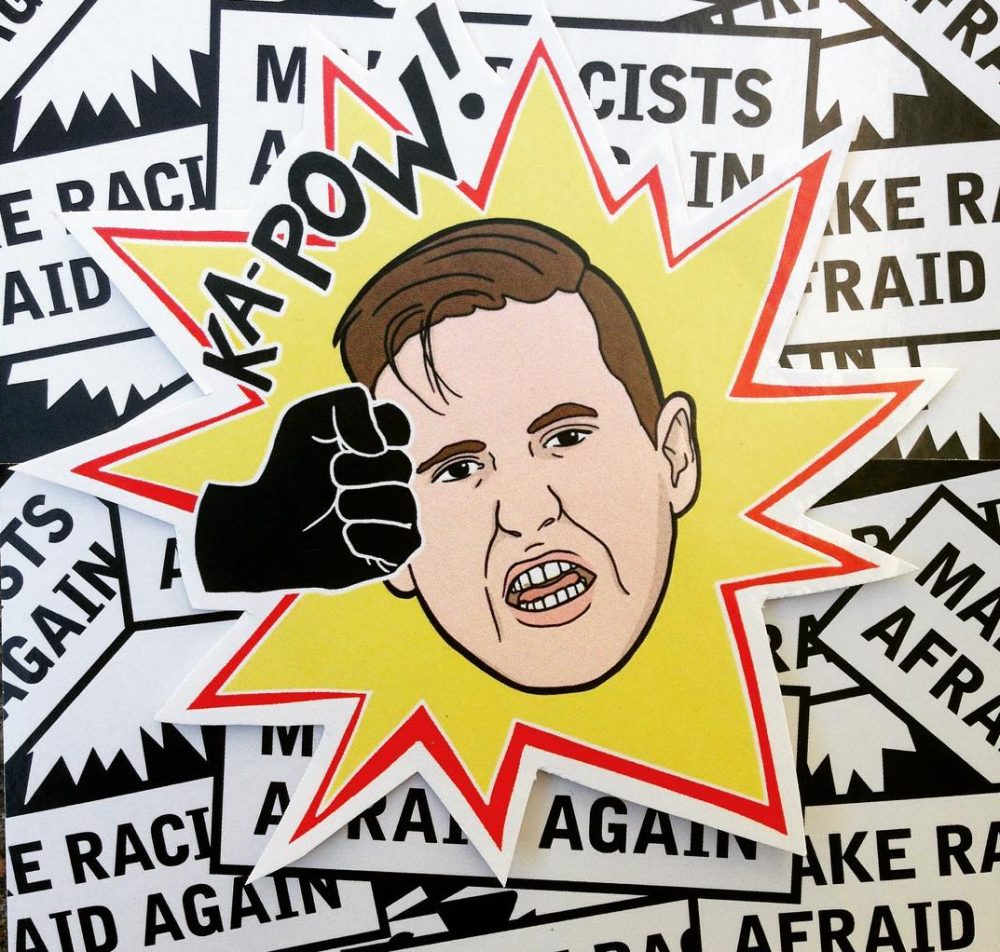

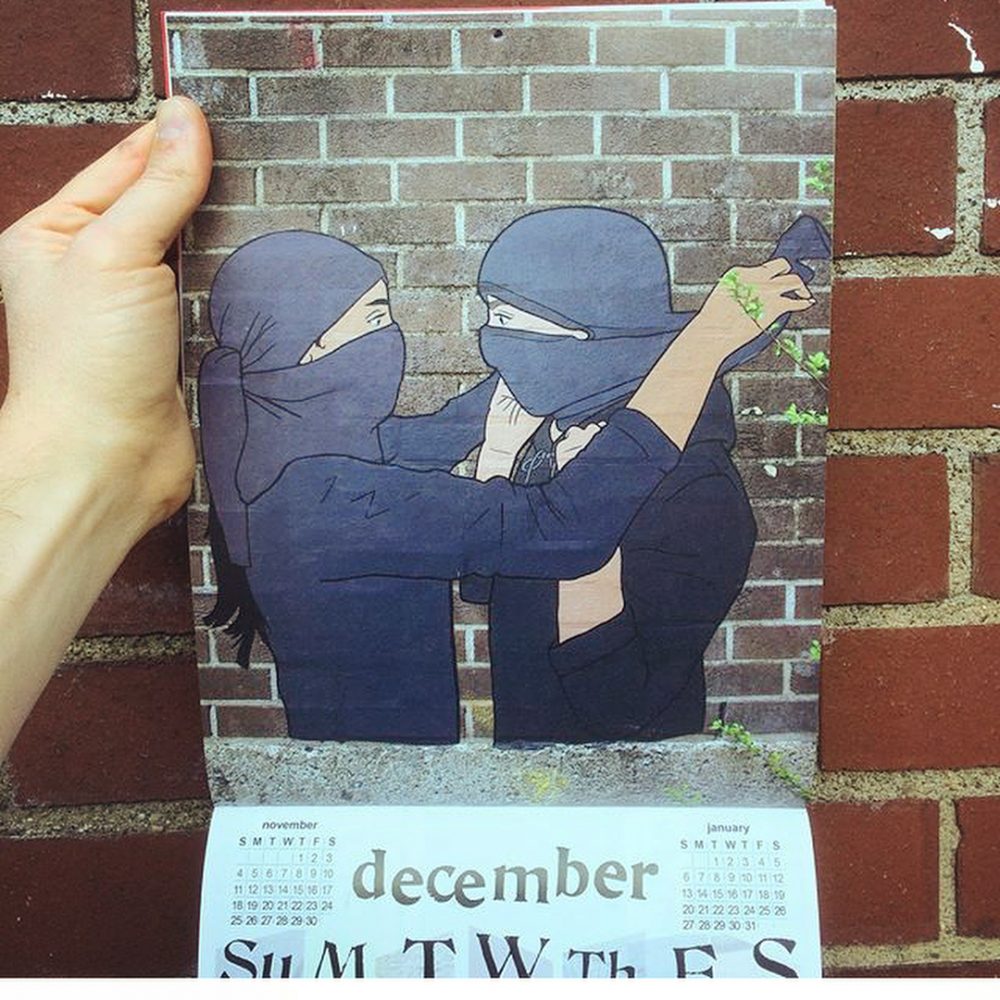

I started illustrating queer and femme black bloc when I felt both the need to address stereotypes of skinny white men as the street fighter figure and the desire to make more visible the presence of radical politics within the city. My experience of bloc is that there are a lot of fucking badass women involved in this tactic but they are often invisibilised by that one louder dude who gets in front of the photojournalist’s shot. I wanted to show a more real and diverse image of bloc peeps and masked protesters.

It was also the year following the 2012 student strike and I felt Montreal needed to normalize the practice of bloc and showing another face of it might remind everyone we out here, we ain’t going anywhere. Since I started this series now 5 years ago, I’ve just pushed the allegory case study as far as I could, questioning the obsession our radical visual culture has with the masked figure.

IGD: So much of the stuff you have put up is so playful and joyful, this seems counter poised to often the more ‘negative’ aspects of anarchist graffiti and street art, even if some of the images you are choosing are clearly “militant.” Is this a conscious choice to present often joyful subjects?

I might have started doing this series with the idea of speaking to the “greater population,” but I feel like with time I felt more comfortable aiming my work to speak to other folk who engage in the struggle. Stumbling upon positive images of resisting figures around the street corner is a boost in morale for my peeps. I don’t know about joyfulness, I still don’t quite get that Spinoza thing. But using bright colors and a tidy illustration style are a conscious choice to divert from the very strict typical anarchist aesthetics. It is a style I naturally tend towards, having read so much manga in my younger years.

IGD: How does street art and graffiti play into the wider anarchist movement in Montreal? Are there lots of anarchist graffiti writers and/or street artists in Montreal and the surrounding area?

Montreal is blessed with a very big bastion of anarchist activism that has influences in many scenes including street art and graffiti. There aren’t really anarchist-identified street artists per se, except me I guess, but radical politics are present in many street artists’ work and a lot of anarchists will go out to put up event posters, stickers, or spend a summer on a street art project.

The city also has its share of anarchist and radical politics related graffiti poetry, slogans and vandalism. You can’t walk two blocks in Hochelaga-Maisonneuve without encountering a sprayed circle A or a “fuck the patriarchy.”

There is also a pretty big graff crew which is/used to be an Antifa gang who did some activism and street fighting. Nowadays they mostly just write NTFA and I would say most of everyone don’t know that their crew name is short for ANTIFA, haha ?

IGD: We know there’s been backlash and heat to anarchists in Ontario as well as MTL Counter-Info, has the spotlight hit your work at all?

To my knowledge, I only get a few lone troll comments once in a while. We do have a small problem with a few active Alt-Right guys in the streets but nothing that worries me. In terms of coppers, well who knows if they are building a file on me?

IGD: Do you feel like images can convey things that words cannot, in terms of political graffiti and art? Seems like an easy thing more anarchists could be experimenting with.

Yes absolutely! I hate how everything is always red and black with a stencil font and has to be so literal. I feel like people are finally getting somewhere creatively with the meme culture and the spread of rad online pages and imagery but anarchism definitely has so much more potential to develop a nuanced visual discourse and different styles.

IGD: We’ve heard in Montreal there is at times a language barrier between Anglophones and Francophones. How do people overcome this?

This is definitely true. I’m francophone, got into rad politics in the francophone student movement. I knew literally not one Anglophone person for years. I was able to break the language barrier by networking with QPPIRG-Concordia groups and make Anglophone friends. Friendship is absolutely the way to go! The city is not that big.

IGD: In terms of large scale struggles or eruptions, such as the student strike in Montreal, how can political graffiti and art play a role?

I see graffiti and illegal street art as direct action. It is a legitimate part of a social movement in itself, disrupting capitalism and taking back public space.

I would even dare say that art and visual culture played a central role in the 2012 Student Strike. I don’t know of an art medium that wasn’t found in the streets in some way or another during that time. One of the main roles of art in social movements is creating an identity people can refer themselves to. There is nothing like a strong sense of belonging to loyalize someone to a cause. It is also a gateway into activism and a real way to play out accessibility within a diversity of tactics strategy. Some might not be able to go to a protest knowing riot cops will be there, but they can come to the stitch and bitch and talk about that last Bell Hooks book they read, or bring their toddler to a live-printing activity in the park before the demo.

More broadly, I think graffiti and street art reflect the people’s ethos, so a revolutionary time will offer opportunity to develop revolutionary street art practices. Mediums are bound to change though, with the evolution of capitalism and the co-option of rebellious cultures. I don’t know which form it will take in the future. We are already seeing a decline in political murals and wheatpaste in the Western World, but people always find a way to be creative in periods of social unrest.

IGD: How can anarchists make better inroads into the broader graffiti culture, which often is very open to the anarchist movement at times?

Art and activism are most difficult to bridge on the cultural level. They are often not the same people: Artists don’t want to go to meetings and anarchists restrain themselves in creative experimentation (they focus on the press release). I’ve experienced this many times when I was the only street artist attending a meeting to plan an activist-led street art outing, or the only activist trying to organize a meeting to plan a street related project with artists. It might seem silly and superficial but culture really does create barriers.

On one side I want to say that Montreal anarchists are already very active with spraypaint. On another, I feel like the local graff culture that belongs to Hip-hop is not in contact with activism, and that both would benefit from meeting in the middle. There has been initiatives like the call for a memorial mural for young Freddy Villanueva who was murdered by police, or the Montreal Sisterhood who used to bridge punk and hip-hop scenes through feminism but that’s kind of dead right now and we definitely need more tryouts like this. Even myself I’ve tried to get in touch with NTFA but kind of failed ultimately.

On a hopeful note, maybe the efforts to support anti-racism and decolonization in the anarchist circles will help open space to broaden collaboration. I definitely have hope it is possible!

IGD: For anyone that is looking at your work and thinking they could do the same thing, what advice would you give them?

Do it! You are the only one stopping yourself from trying. Things fall into place only a while after you start out. I started with no activist network, no knowledge in graff culture, no ability in drawing. I found a way to make it work with my first strength: staying home on photoshop a lot, and made some good friends along the way.

IGD: Any parting thoughts? How can people view your stuff and support your work?

I hope people find the strength to take it to the streets and log off their social media accounts more and more. Posting critical content online is great, but the revolution will not be on fucking Twitter.

I have a small shop for people who want to get my work for cheap at zolamtl.storenvy.com and encourage everyone to follow campaigns and groups I work with or support such as Unceded Voices, Solidarity Across Borders, and Racines Bookstore.

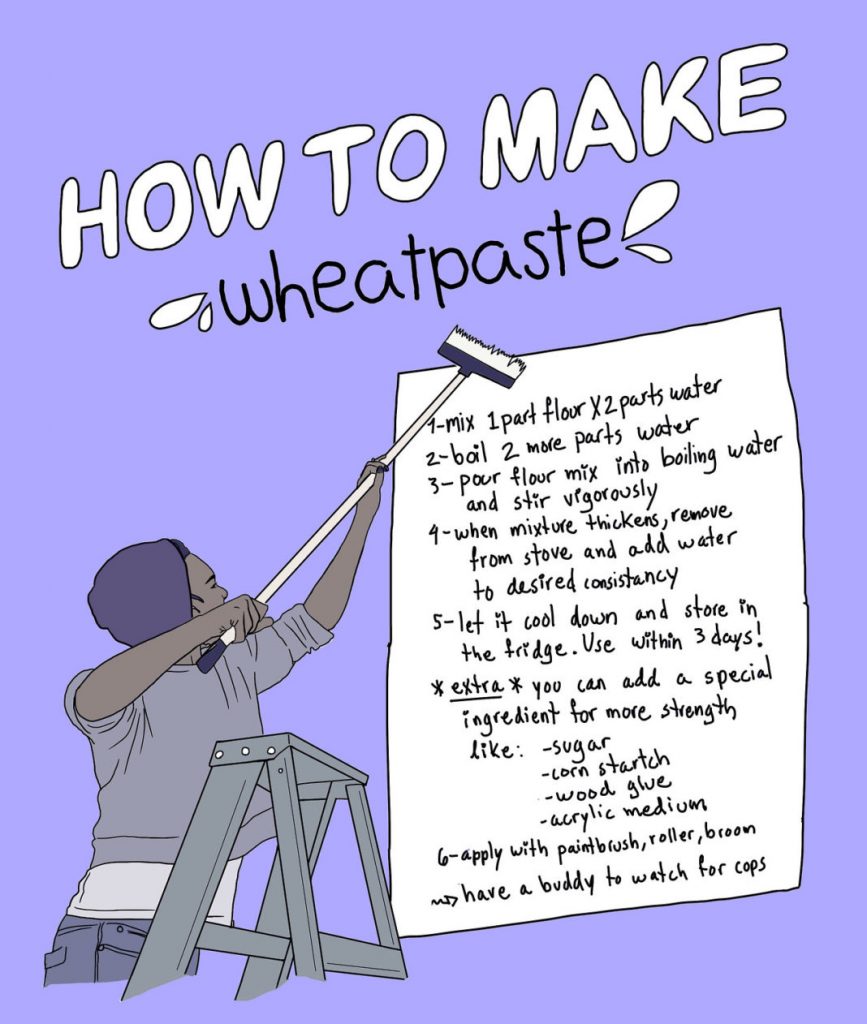

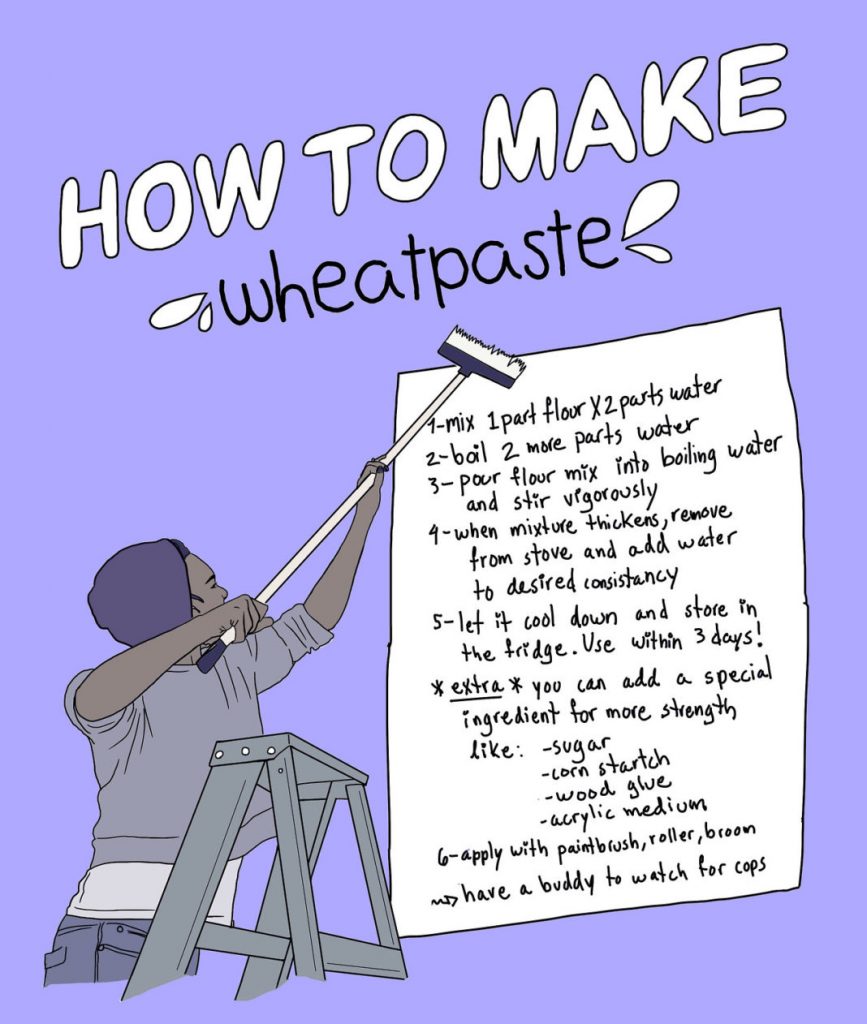

IGD: Is boxed wheatpaste better than homemade? And if not, what is the BEST homemade wheatpaste recipe out there?

I never bought boxed wheatpaste? There is nothing like the ritual of cooking your dough before an outing, I wouldn’t change it. As for a *best* recipe, when I feel like a rich and famous artist, I add acrylic mat medium to the mix and it does wonders for UV protection.