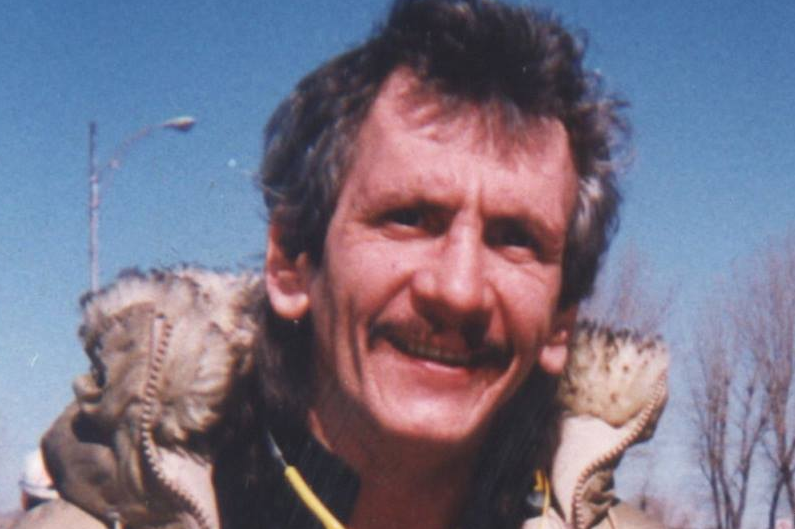

On September 5, 1999, eighteen years ago, Jean-Pierre Lizotte died as a result of injuries sustained from the blows of a Montreal police officer. I’m re-sharing today an article that I wrote in 2008 (published, in a slightly different form, in the Montreal Gazette) about the “Poet of Bordeaux Prison”. RIP Jean-Pierre Lizotte!

The Gazette’s opinion pages recently provided space to the lawyer for Montreal police officer Giovanni Stante who was charged in the death of Jean-PierreLizotte in 1999. The lawyer takes offense to a Gazette report, subsequent to the police killing of Freddy Villaneuva in Montreal-Nord in August this year. He feels that the report gives the “false impression that Lizotte was a victim of police brutality.”

Stante’s lawyer reiterates that Officer Stante was acquitted by a jury in 2002, and cleared by the Police Ethics Tribunal for inappropriate use of force just this past August 2008. Those are cold, hard facts.

However, there is one eyewitness to the events on the early morning of September 5, 1999 outside the Shed Café on St-Laurent Boulevard who will never get to tell his side, and that’s Jean-Pierre Lizotte himself. Lizotte died subsequent to the substantial injuries he suffered.

Yet, while vigilantly defending Officer Stante almost a decade after the incident in question, Stante’s lawyer goes on to cite Jean-Pierre Lizotte’s extensive criminal record. Dead men tell no tales, as the saying goes.

Fortunately, in the case of Jean-Pierre Lizotte, despite two decades in-and-out of prison, this particular dead man had a lot to say, and he said it, poignantly and insightfully. He deserves his voice too, in these pages, as much as Officer Stante has his voice through his lawyer’s skillful advocacy.

Thanks to a remarkable radio program called Souverains anonymes, which encouraged the creative side of prisoners at Bordeaux, we still have a record of many of Jean-Pierre Lizotte’s words.

After learning of his death, the producers of Souverains Anonymes recalled something Lizotte wrote to Abla Farhoud — a Quebec playwright, writer and actress, originally from Lebanon — who had participated in one show at the Bordeaux prison. Lizotte was responding to the words of the main character of Farhoud’s novel, Le bonheur a la queue glissante, who observed, “My country is that place where my children are happy”.

As an immigrant rights activist, deeply immersed in migrant justice struggles, and indelibly touched by my mother’s own immigrant experience, Lizotte’s response to Farhoud is moving, as he seeks common ground while reflecting on his own life; it’s worth citing in full:

“Hello Abla, my name is JP Lizotte. For the 21 years that I’ve been returning inside, prison has become my country. When I leave it, I become an immigrant! I experience all that an immigrant might experience when they miss their country of origin. When I’m inside, I want to leave. And when I’m outside, I miss the inside. Sometimes I say to myself, “If I had a grandmother or a grandfather, things would have been different for me.” But how can you have a grandmother when you’ve hardly had either a mother or father. The memories that I have make me cry, so I won’t tell them to you. But, a grandmother, like the one in your novel, is not given to everyone. So, I say to everyone who has a grandmother or grandfather, take advantage of it. Thanks.”

There are clear underlying and understandable reasons why Lizotte was in-and-out of prison for more than two decades, beyond the list of criminal offenses that Officer Stante’s lawyer provides, without any context.

His fellow prisoners dubbed Lizotte the “Poet of Bordeaux”, and he wrote prolifically. His poems were in a rhyming and often humorous style that address deeply personal themes: his difficult childhood, his lack of a caring mother, his father’s alcoholism, depression, his HIV-positive status, his drug problems, along with subjects like music, prison and revolt. He even wrote an unpublished memoir about his itinerant life called, Voler par amour, pleurer en silence.

Jean-Pierre Lizotte came from a harsh-lived reality, right from his childhood, as he shared in his poems and writings with simple honesty.

On the late night of September 5, 1999, on a trendy and expensive part of St-Laurent Boulevard, Jean-Pierre Lizotte’s reality came up against the contrasting reality of restaurant patrons, bouncers, and police officers. Lizotte was allegedly causing some sort of disturbance, and he had to be restrained in a full-nelson hold and punched at least two times by Officer Stante’s own testimony (some witnesses claim that Lizotte was punched “repeatedly” and excessively). According to eyewitnesses, there was a pool of blood left at the scene. One eyewitness refers to Lizotte being thrown into a police van “like a sack of potatoes”.

Officer Stante was duly acquitted by a jury in 2002; so were the officers in the infamous Rodney King beating, or more recently the New York City officers who shot and killed the unarmed Sean Bell on the day of his wedding. Police officers are routinely acquitted – if ever charged — within a criminal justice system that appropriately demands proof “beyond a reasonable doubt” before conviction.

Officer Stante might stand acquitted, but it’s still completely valid, and necessary, to question the actions of the Montreal police, despite the police procedures that apparently allow for the punching of an unarmed man held by another officer for the purposes of restraining a suspect. One simple fact that readers should consider: the police did not reveal Jean-Pierre Lizotte’s death in 1999 to the public until 53 days later.

But, what if there was a video of what happened outside the Shed Café in 1999 instead of the imperfect and contradictory memories of eyewitnesses at 2:30 in the morning? What if Jean-Pierre Lizotte was present in the courtroom, in a wheelchair and paralyzed, in front of the jury’s own eyes?

At Stante’s trial, and again in your pages, Officer Stante’s lawyer puts a dead man who can’t defend himself on trial. Lizotte transparently acknowledged who he was. What’s cheap is to still deny Jean-Pierre Lizotte – the homeless “criminal” — his full humanity and dignity, because he possessed it in such abundance.

– Jaggi Singh (September 2008), member of Justice for Victims of Police Killings and Solidarity Across Borders (Cité sans frontières / Solidarity City / Ciudad Solidaria (Montréal))