From Crimethinc

This is the final installment in our “After the Crest” series exploring how to navigate the waning phase of social movements. It is a personal reflection on anarchist participation in the 2012 student strike in Montréal and the disruptions that accompanied it. The product of much collective discussion, this article explores the opportunities anarchists missed during the high point of the conflict by limiting themselves to the framework of the strike, and the risks they incurred by attempting to maintain it once it had entered a reformist endgame.

For a narrative account of many of the events discussed in this text, read While the Iron Is Hot: Student Strike and Social Revolt in Montréal, Spring 2012.

Timeline

February 13, 2012. After many months of ultimatums to the government, mobilization on university and cégep campuses, and occasional actions and demonstrations, the student strike officially begins with a few departments at Université Laval in Québec City. From there, it spreads rapidly. Spring has come early.

February 16. The student association of Cégep du Vieux Montréal votes to go on strike; the school is occupied. Late in the night, police enter the school and break up the occupation.

March 15. After weeks of escalating violence on the part of the police, including an incident in which a cégep student lost his eye to a concussion grenade, the COBP’s annual demonstration against police brutality begins at Berri Square; the crowd that gathers is significantly larger than at any other time in the history of the event, and a night riot ensues. Although many participants escape, over 226 are arrested.

March 22. The largest demonstration of the strike thus far is an ultimatum from the Coalition large de l’Association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante (CLASSE) to the Liberal government in Québec City: repeal your planned tuition hike, or we will begin a campaign of economic disruption. Although actions to this effect had already been taking place in Montréal, from this point on, they to begin to occur more frequently and with more ambitious objectives.

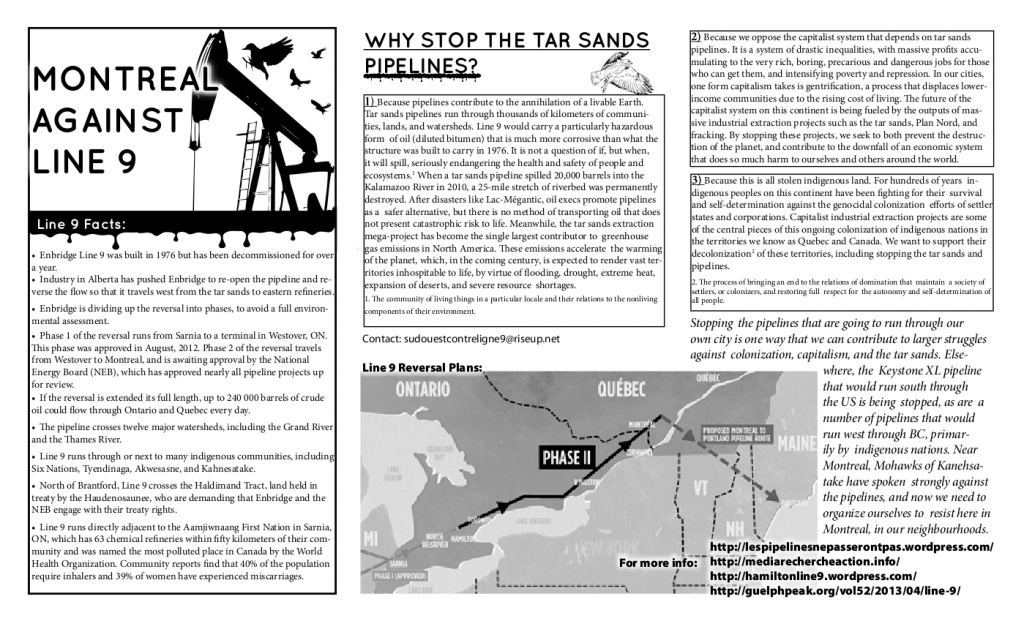

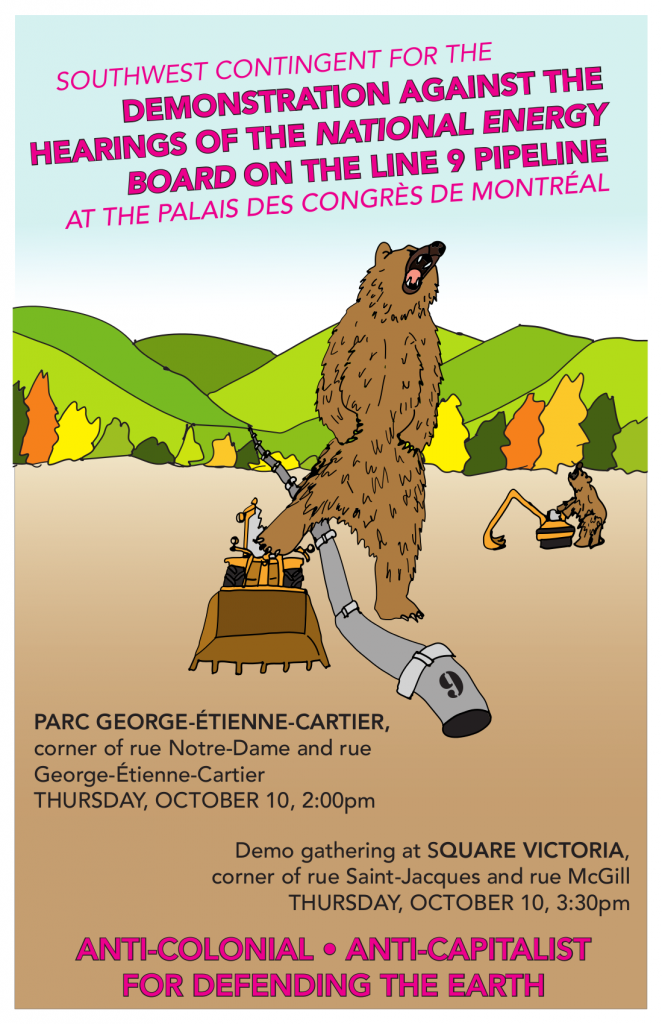

April 20. The Salon Plan Nord, a job fair, takes place at the Palais des congrès. Jean Charest is there to deliver a speech about his government’s plan for the accelerated development of Québec’s portion of the Labrador Peninsula—land which is still inhabited, for the most part, by indigenous people determined to live as sovereign, autonomous nations. The single largest street battle of the strike unfolds, paralyzing a large section of downtown for hours and capturing international headlines. For the first time in the strike, cops flee demonstrators. Its significance is immediately apparent to anarchists. Yet no one can predict how intense things will get.

May 4. A truce between the students and the government has come and gone. Angry night demonstrations have taken the streets, then been pacified; morning blockades of highways, skyscrapers, and other targets have ceased altogether. People have barely caught their breath from the largest anti-capitalist May Day demonstration in recent memory. And now buses from across the province are unloading militants of all sorts in the small town of Victoriaville; the goal is to disrupt the Liberal Party convention that was scheduled to take place at a Montréal hotel, then hastily transplanted to the countryside. The clash between demonstrators and the Sûreté du Québec police force is brutal; people on both sides are badly injured, but the red squares get the worst of it. Another person loses an eye; still another is put into a coma. Things don’t feel as good as they did two weeks prior.

May 10. The streets of Montréal have been peaceful for a few days, but this morning, smoke bombs go off in four métro stations across the city; the whole system is shut down for hours. Thanks to a good citizen with a cellphone, the Service de police de la Ville de Montréal (SPVM) releases pictures of some suspects on its website the same day, and four people surrender at a police station soon thereafter.

May 18. Two new laws come into effect at midnight, both of which restrict the ability of participants in the strike movement to act. The night demonstrations turn confrontational again around this time, but despite heroic efforts against the police, the movement is unable to assert itself in the streets as effectively as it did a month earlier. That said, more people are participating than ever before. Spontaneous demonstrations begin in neighborhoods across Montréal, helping new neighborhood assemblies to take off.

June 7. The Canadian Grand Prix begins with a rich bastards’ gala. Militants fail to disrupt it, but over the next few days, despite a seriously compromised rapport de force with the police, they succeed in disrupting Montréal’s most important tourist event of the summer. Many inspiring things happen; yet it is clear that the movement is on the decline.

August 1. Confirming what people have suspected for weeks, the premier calls a general election for September 4. The Parti Québécois asks the movement to agree to an “electoral truce.”

August 13. Classes at some cégeps are scheduled to begin. School authorities, however, shut down classes so that anti-strike students can attend general assemblies on the matter of continuing the strike. Of the four cégeps voting on this matter, three vote to end the strike; they join schools that had voted similarly in the days prior. Except for a few departments at UQÀM, the strike collapses almost entirely over the next few weeks—though demonstrations continue, sometimes turning confrontational.

September 4. When the votes are counted, the PQ has won a majority in the National Assembly. The tuition hike is canceled by decree a few days later. Some call it victory.

Foreseeing Events

Anarchists should hone our skills at anticipating social upheavals.[1]

Sometimes, such events can be seen coming far in advance, offering us the chance to prepare in order to surpass the limitations of the organizations, discourse, and default tactics that are likely to characterize them. That was the case in Montréal in the summer of 2011, by which time it was perfectly clear that a student strike was on the way. By the middle of summer, it was widely known that the major student federations, ASSÉ, FÉCQ, and FÉUQ, were collaborating for a massive demonstration on November 10. This demonstration was conceived as presenting the Liberal government with an ultimatum before the movement resorted to an unlimited general strike. Earlier in 2011, the occupation of the capitol building in Madison, Wisconsin, had taken me and many other anarchists across the continent by surprise. In Montréal, on the other hand, we had advance warning of things to come; it was clear to some of us that we could make strategic use of this knowledge.

A correct analysis of any situation, combined with reflection on one’s own objectives, should suggest a strategy with which to proceed.[2] But how do we refine our analytical skills? I don’t want to reduce this to experience; plenty of “veterans” analyze situations badly, routinely making the same mistakes. In Montréal, that camp includes those who fetishize direct democracy, certain types of collective process, and the global justice movement that peaked here in the mobilization against the 2001 Summit of the Americas in Québec City. Québécois insurrectionists tend to dismiss that crowd—perhaps too hastily—as being attached to a romanticized notion of anti-capitalist struggle in Montréal at the turn of the millennium. And yet older insurrectionists are also guilty of using the same tactics that they’ve been using for years, often with no better sense of the political context than the younger people they are lecturing.

Rather than deferring to age and experience, we can sharpen our analytical skills through discussion groups, general assemblies oriented towards communication as an end in itself, and more writing, theorizing, and critique. These are the processes that enable a crew, a community, or a distributed network of subversives to gain mutual understanding and refine their analyses in order to speak precisely about what is happening, what must be done, and—most importantly—how to do it. It is essential to find the time and space to do this with people you trust, whose analysis you also trust, and ideally who come from a range of backgrounds and experience.

This isn’t a recipe for success. The future can’t be foreseen with total accuracy. But things sometimes play out in similar ways over and over again. There are patterns we can identify. We have a better chance of finding them if many of us are looking, and even better if we disagree on some things and draw on different knowledge.

If anarchists don’t improve our ability to foresee events, we will keep repeating two grievous mistakes. First, we won’t know when it’s time for us to throw ourselves into a struggle with everything we’ve got—when the risks are worth the possible consequences. Alas, many anarchists in Montréal waited until far later than would have been ideal to get involved in the student strike. Second, we won’t recognize when we should withdraw because the movement is headed toward a catastrophe that will hurt us—as the events of August 2012 did, at the end of the strike.

Once the school year started, some anglophone anarchists from outside the university, or who were students but who mostly organized outside of student spaces, made a concerted effort to insert themselves and anarchist ideas in general into student organizing at McGill and Concordia. This was sometimes as sloppy and disorganized as the individual anarchists involved. But that didn’t matter; what mattered was consistency. Local anarchists’ distribution of certain texts at McGill, such as After the Fall and “Communiqué from an Absent Future,” probably contributed significantly to the occupations that occurred on McGill campus during the 2011–12 school year, both before the strike even started.

Many of the texts distributed were written in inaccessible insurrectionist jargon; anarchists often came off as total wingnuts. But the point was not to appeal to the masses. It was to make connections with specific people who would be participating in the strike when it began— a process that was developed further by inviting people to events at La Belle Époque, the newly-opened anarchist social center in the Southwest, or just by hanging out. This, in turn, encouraged those people to expand the discourse of the strike to other areas: struggle in defense of the Earth, against the police, against racism and colonialism, and so on.

Student militants at the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQÀM) and Cégep du Vieux Montréal had been organizing for much longer. These two schools, from which other strikes had historically emerged, were also the source of most of the momentum for the 2012 strike. Although both schools already had a strong radical presence, political graffiti within certain buildings was ramped up in the years before the strike. Occupations and demonstrations were organized. In early 2011, Hydro-Québec’s downtown headquarters was smoke-bombed by students from Vieux, forcing an evacuation. There was also a lot of work behind the scenes—distributing propaganda, organizing informative assemblies, and the like. Syndicalist anarchists participated actively in their student associations and in the Association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante (ASSÉ); this meant office work, balancing finances, writing articles for ASSÉ’s newspaper Ultimatum or for individual associations’ broadsheets, and a lot of organizing limited by the discourse of the official student movement. Some anarchists have been critical of this approach, but there’s no question that anarchists on the whole benefited from the fact that some people were doing this.

Syndicalist methods created the strike; it could be argued that they also created the limitations that would ultimately produce the movement’s downfall. A point that is sometimes missed, however, is that every social upheaval will have built-in limitations, and there isn’t even a chance to overcome those limitations until the upheaval exists as a material reality. Despite the tensions that existed between various anti-capitalist and pro-strike factions at Cégep du Vieux and UQÀM, it is clear that the lowest-common-denominator mobilization approach of creating opposition to the tuition hike complemented direct action, if only by fostering a political environment in which other students could understand why “the issues” were serious enough that some people would take such action.

“Fuck fascists, therefore fuck the administration.”

Graffiti at Cégep du Vieux Montréal before the strike.

Crises create opportunities. This is perhaps the most important maxim for anyone who wants to defend land, freedom, and dignity against the ravages of capitalism. In this context, it is problematic that many anarchists, in the years before the strike, were willfully ignorant of the political machinations that produced the flashpoint of the strike. It took a long time for anarchists who had been following the developments to convince their comrades of the importance of the impending events.

Of course, given the right circumstances and skill sets, we can generate crises ourselves. This is exactly what some anarchists, upon finding themselves as students at institutions with a tradition of direct democracy and a history of strike-making, proceeded to do in the years leading up to 2012—just as other anarchists had done in the years leading up to 2005 and earlier strikes.

Anglophone anarchists in Montréal—many of whom grew up in other provinces or in the US, whose French is marginal at best, often possessed of rather few francophone friends, frequently either university dropouts or enrolled at schools with less interesting political cultures—were usually not as disposed to help produce a crisis. This was also true of older anarchists, those with jobs, or those on welfare and genuinely poor; in essence, non-student anarchists of all language backgrounds. But, though anarchists from certain social positions may not have been able to contribute as much to making the strike happen, there was plenty for those people to do to improve their capacity to participate in the strike once it began.

The most important thing is consistency—doing what you can from where you are. It doesn’t matter how limited your abilities or social position are. If you don’t drop the ball, you’ll eventually get a chance to shoot.

If you don’t drop the ball,

you’ll eventually get a chance to shoot.

Seizing the Peak of Opportunity

Though some prepared for the strike itself, few did anything to prepare for the situation that arose from it: the peak of opportunity.

There were two such periods, actually. One started on April 20, 2012, with the protests against the Plan Nord conference, during which it became clear that the police were temporarily outmatched, and lasted until May 4, when it degenerated into more brutal and less inspiring violence at the Liberal Party convention in Victoriaville. This was a period when so much could have been done, and yet many insurrecto-hooligans contented themselves with mere rioting—as exciting as that may have been. Soon enough, it was no longer fun. It wasn’t just random unfortunates with presumably little street experience who were getting arrested and injured, but ourselves and our friends as well. This is all the worse because almost anything could have happened in Montréal at that time if people had been able to step back from the whirlwind of events, gather their comrades, identify an objective, and act.

Friday, April 20 – inside the Palais des congrès.

Wednesday, April 25 – central downtown.

Tuesday, May 1 – central downtown.

Friday, May 4 – outskirts of Victo.

In point of fact, it seems this did happen, but perhaps too late. On May 10, the most effective sabotage of the Montréal métro to date took place, with smoke bombs going off at four different stations across the city. If such an act had occurred during a large demonstration or riot in downtown Montréal, it could have created an even more uncontrollable situation across the island—perhaps opening new windows of opportunity for anarchists and others to seize territory or go on the offensive. By May 10, however, an uneasy peace had taken hold in Québec with the pacification of the night demonstrations and the passing of the last spectacular clashes during daylight hours, May Day and the Battle of Victo. In this context, the smoke bombing incident appeared as a daring attempt to reignite conflict, not as a conscious effort to expand its scope at the height of things.

The period that started on April 20 was not a revolutionary moment, but perhaps only because no one proposed, via words or action, to take the logical step from mass vandalism to the collective expropriation of goods and seizure of buildings—the kind of activity that would have quickly brought out even larger crowds than were already participating in the strike. Things might have gotten a little nasty after that, no doubt, especially given the lengths to which the state is willing to go to uphold the institution of private property. But had things escalated to this point, the revolutionary potential of the situation would have become apparent to everyone.

There was a second peak of opportunity a few weeks later, and it too was squandered.

To be clear, the opportunities that this second peak presented were not produced by militants’ capacity to maintain a rapport de force with the police. On the nights immediately before and after the government passed its Special Law to crack down on the strike, there were major street battles that lasted long into the night, probably involving the largest numbers of any post-sundown street action and certainly producing the largest mass arrests. But while many experienced these clashes as inspiring, including many out-of-town anarchists who had shown up for the anarchist book fair, the battles proved ephemeral. They were the final and most spectacular clashes of a movement that was rapidly losing the capacity to go toe-to-toe with the police that it had gained in the early months of the strike, and particularly between March 22 and May 4.

New opportunities were produced, though, by the expansion of anti-government sentiment to parts of society that hadn’t previously been involved in the strike. Suddenly, there were small roving demonstrations in neighborhoods across the city and in cities across the province. A sizeable number of these people were said to have supported the tuition hike, but fundamentally objected to the government’s “anti-democratic” means of defending the capitalist economy and its monopoly on violence. The numbers also grew downtown; the demonstration on May 22 may have had as many as 400,000 people.

A demonstration in the neighborhood of Saint-Henri on Thursday, May 24.

This opened up a moment akin to the Occupy moment in other places.[3] What happened is that people with radically different ideas were meeting in the streets, vaguely united by their opposition to how things were going in their society. Perhaps they were excited by the energy of the moment; perhaps they were open to challenging preconceived notions about how things should be, and how to get there.

This didn’t happen on the scale that it could have. Many anarchists cited the shortcomings of the casserole demos and the neighborhood assemblies to justify not engaging with them. Of course, there were shortcomings; that’s to be expected whenever people more familiar with obedience to authority suddenly opt for defiance. Their strategies, rhetoric, analysis, and even attitudes weren’t always ideal from an ideologically purist anarchist perspective. But this was as true of those who fought in the streets—including those young and patriotic Québécois men who saw their combat with the police as a continuation of the FLQ’s hypermasculine methodology—as it was of those who opted to bang pots and pans or to participate in the “popular neighborhood assemblies” that had, in many cases, devolved after a few weeks into hangout spaces for all the local weirdos interested in radical politics.

A popular assembly in the Plateau on June 10.

The important thing here is that the confrontations of the book fair weekend marked the point when street fighting downtown started to deliver diminishing returns, in terms of its ability to disrupt the capitalist economy and improve the movement’s rapport de force with the government. At that point, it was probably more feasible to broaden the disturbances than to escalate the ones already taking place.

Both peaks of opportunity, starting on April 20 and May 18 respectively, involved peak numbers of people engaging in particular activities—either the specific activity of fighting the police during the first peak, or the general activity of participating in the strike movement during the second. These were our chance to reach out to all the people whose political analyses, experiences, or backgrounds were different from ours. Most of them knew what they were there to do. If anarchists had articulated to others a method of how to do it while also encouraging people to go farther, it’s possible that the movement could have reached still higher peaks.

Quit While You’re Ahead

The strike didn’t die over the course of the summer. It stagnated.

After the Grand Prix, the demonstrations and meetings continued—quite a lot, in fact, albeit less than during the spring. June 22 and July 22 saw tens of thousands of people come out; not a single night demonstration failed to take the streets. There was a bit of a ruckus in Burlington, Vermont, when premiers and governors in the northeastern part of the continent met there at the end of July. Plans were drawn up for a convergence for the rentrée (the return to classes and the recommencement of the suspended semester) in August, starting first at cégeps and then moving on to universities.

All of this happened, yet none of it materially improved the strike’s prospects for defending itself, particularly in the face of an election campaign—one of the most effective tactics democratic states have at their disposal to shut down social movements. It had been suspected for weeks, then essentially confirmed in the days immediately prior, but Jean Charest, the premier, made the official announcement on August 1.

Incidentally, August 1 also marked the hundredth night demonstration

in a row since April 24.

The Parti Québécois offered a deal to the movement: settle down a bit, we’ll win this election, and then we’ll suspend the hike. It was argued, not unreasonably, that disruptive activity could hurt the PQ’s chances of beating the incumbent Liberals. Consequently, pacifist vigilantes stepped up their efforts to interfere with confrontational tactics at the night demonstrations, and the cégeps unanimously voted against the continuation of the strike. The strike did continue in some departments at UQÀM, but the effect was marginal, and efforts to enforce a shutdown of classes were undermined by scabs, security, and police.

Anarchists had taken many risks and suffered severe consequences in their efforts to strengthen and embolden the movement as a whole. Many had already been beaten and arrested, and faced charges and uncertain futures. More than any other political tendency involved in the strike, anarchists were the ones who escalated the situation to the point that Jean Charest was forced to call an early election to end the crisis. Yet despite our best efforts, we had become foot soldiers for a movement that had always had a nationalist, social-democratic, and reformist character. Now this movement no longer needed us to win its unimaginative and ultimately shortsighted baseline objective: the cancellation of this specific tuition hike. It became difficult to avoid the conclusion that we had been used. Many of us felt, perhaps irrationally, that our efforts over the past few months had been utterly in vain. We told ourselves that we had gained experience, friends, and so on, that we had been part of something “historic,” but this sort of positive rhetoric failed to improve morale. In some cases, it just made things worse.

Since the strike’s end, many anarchists have argued that we failed to apply the right tactics to the situation. What could we have done differently? What would have produced a greater success for us in August?

But this line of critique may miss the mark. Perhaps we should step back and ask whether it was strategic for anarchists to try to revive the strike after militancy had withered over the summer. At the time, everyone embraced the “common sense” assumption that the top priority was to keep the strike alive. Hindsight is 20/20, but the negative consequences of that approach should have been predictable.

Maybe, instead, we should have just gotten out of there.

Now, I am not proposing that we should have withdrawn all support from the strike, but that we should have withdrawn some forms of support, especially the ones that involved considerable personal risk. Anarchists had previously proven capable of this. Many anarchists withdrew at the right time during the occupation of Cégep du Vieux Montréal and the night riot of March 15. In doing so, they left less experienced participants to face their fate alone—resulting in mass arrests in both cases. This was a little callous, no doubt; but during both events, anarchists made a point of offering advice to people who were making some pretty questionable decisions about how to conduct themselves. Anarchists eventually—and in my opinion, correctly—decided to take care of themselves once it was clear that things were about to get ugly and that their suggestions were falling on deaf ears. And in the aftermath, anarchists organized support for those arrested.

Regarding the strike as a whole, getting out wouldn’t mean, for example, anarchists suddenly abandoning their critical support of the idea of free education. A common denominator position among anarchists in Québec, from syndicalists to anti-civ nihilist types, is that Québec’s privileged proletariat deserves the nice things in life—like a useless liberal arts education—at least as much as Québec’s even more privileged ruling class. To say it differently: “If capitalism, then at least welfare capitalism.”

Making a strategic exit wouldn’t have stopped anarchists from intervening where it made sense to do so, either—but it would have meant that anarchists ceased helping the student movement whenever it stumbled, talking confidence into it whenever it hesitated, and trying to knock some sense into it whenever it was about to go in a stupid direction. In many ways, anarchists related to the student movement the way you might relate to a partner—in this case, an overly dependent partner who was not very appreciative of the help we often offered him unconditionally, sometimes was downright emotionally abusive, and really, do we even like this guy that much?

But anarchists often lack self-confidence. Sometimes we don’t know when it’s time to cut our losses and move on. We were under the impression that we needed the strike to go on in order to continue building up our own power. Yes, we had invested a lot in the movement, and it would have felt wrong just to pull out and let it do its own thing—which, no doubt, would have left us shaking our heads in exasperation. But was it really a good idea to invest even more in it when things were evidently headed in an ugly direction?

Our efforts to revive the movement did a lot to hurt the momentum that anarchists in Montréal had been building, in stops and starts, for years—since long before the strike. This set us up for disappointment and depression, needlessly demoralizing and demobilizing us. The problem was that we were pursuing a grossly unrealistic objective. The option of continuing the strike, especially given the general decline in confrontational activity during the early part of the summer, simply could not compete with the option of electoral compromise with the PQ. Democratic ideas have significantly greater sway in the student movement and among the general population than anarchist ideas. As unfortunate as this is, we should recognize this and act accordingly.

Missed Opportunities

The worst thing about the decision to prioritize continuing the strike was that, at that point, there were plenty more interesting and worthwhile paths open. For example, we could have focused on resisting and counteracting state repression. Repression had affected anarchists the most severely, but it also affected revolutionaries from other tendencies—most significantly Maoists—as well as many people who had simply been caught up in the energy of the strike and received criminal charges as a result.

“The strike continues on August 13!” Many militants suffered from tunnel vision in August, doing what they could to prove this poster true— but at a heavy cost for other fronts of the struggle.

During the spring, anarchists organized some powerful noise demonstrations, and there were also actions at Montréal’s courthouse, the Palais de justice. After the strike was over, in fall 2012, a large and spirited demonstration took to the streets in solidarity with everyone facing charges, living with restrictive conditions, or otherwise suffering as a result of things they had been accused of doing during the strike. Various texts appeared on this topic, as well. Yet at the end of the summer, during the period of the election and the rentrée, there was no organizing to speak of on that front.

The only thing anarchists did collectively in August, besides attempting to stop the rentrée, was to campaign against representative democracy itself. This could have been a promising terrain of struggle, but almost everyone involved was also wrapped up in the losing battle of continuing the strike. Things didn’t turn out well on either front—but even more importantly, both undertakings were posited by the anarchists involved as being in solidarity with the student movement, when it was precisely the student movement that was facilitating the isolation and repression of anarchists by abandoning the strike.

In other words, the student movement was acting contrary to the principle of solidarity. And by buying into the PQ’s proposal for an “electoral” truce, the student movement sabotaged its own most basic objective, with the PQ ultimately implementing indexation rather than a true tuition freeze.

As a side point, it’s both facile and inaccurate to blame movement leaders and politicians for this turn of events. The strike was voted down in directly democratic assemblies. No matter how loud and influential certain individuals were, it was the students as a whole who chose to abandon the strike.

The hopeless attempt to save the student movement from itself took away from the effectiveness of anarchists’ anti-democratic campaign. It was basically the same people doing everything, and they didn’t have the energy to do everything; their energies were split between appealing to students to keep the strike going, and appealing to society at large not to vote.

“The elections… We don’t give a fuck! We don’t vote; we struggle.”

Anarchists saw these as identical, which was a poor understanding of the social reality. For one thing, there was the statist, reformist, pro-voting stance of the majority of the student movement’s participants—but do we really need to beat that particular dead horse any longer?

Meanwhile, a lot of people living in Montréal have a difficult time simply surviving because of the neighborhood they live in, the color of their skin, their lack of citizenship or status, or their accent in French—if they can speak it at all. There’s no doubt that plenty of marginalized folks were down with at least certain aspects of the student movement. But neither is there any doubt that most of them had only limited interest in the self-centered struggle of a bunch of privileged brats who, broadly speaking, did not reciprocate by concerning themselves with the more dire struggles of migrants, indigenous people, and others.[4]

Now, I’m not saying you need to take off your red square if you want to start talking to such people about the moral bankruptcy of democracy. But maybe the fact that the PQ is going to sell out the movement shouldn’t be the center of your analysis if you want to address people who aren’t particularly invested in the movement. All the adamant social democrats to whom anarchists’ analysis of the situation might have been useful—given that they were legitimately seeking a freeze, not indexation—were completely unwilling to listen to anarchists during election time. That was their mistake. But our mistake was to keep trying to get through to the social democrats rather than reaching out to others who might have been a little more open had we been less alienating.

It’s hard to imagine that the results could have been worse than what actually happened if, instead of trying to engage students and other participants or supporters of the movement with anti-electoral ideas, anarchists had used the same time and energy to advance a critique of Québécois democracy by other means. Sure, I’m skeptical that dropping a banner emblazoned with the words NEVER VOTE! NEVER SURRENDER! À BAS LA SOCIÉTÉ-PRISON «DÉMOCRATIQUE!» from a train bridge in a neighborhood full of francophone pensioners, then failing to publicize that this even happened, is the best use of anyone’s time. But as confusing, poorly contextualized, and silly as that might be, at least it speaks for itself without centralizing the students’ struggle to preserve their privileged position in society.

It’s interesting to think about what other projects anarchists could have undertaken, unencumbered by the student movement. What if anarchists, in neighborhood assemblies or more informally, had pushed a struggle against gentrification and manifestations of capitalism in the areas where we actually live, while police resources were tied up watching night demonstrations and maintaining order downtown? In other words—what if we had taken advantage of the political situation to improve our own long-term material position, rather than improving the rapport de force between the government and the students?

We also could have done more to usurp the megaphone, both literally and figuratively. This happened earlier in the strike: on the night of March 7, after a demonstrator lost his eye to an SPVM grenade, anarchists shouted down a few self-appointed leaders’ appeals for people to express their outrage peacefully, successfully convincing the majority of the crowd to stop standing around in Berri Square and either physically confront the police or at least defy their commands to disperse. There were attacks on two different police stations that night, the first such actions of the strike.

In August, as on March 7, there were crowds of outraged people, but this time, they weren’t outraged about police violence. Instead, as an outvoted minority, they were upset by their fellow students’ decision to abandon the strike. The situation was a bit different: to go the fighting route would have meant ignoring the final verdict of a directly democratic vote, not just a few people with megaphones. In retrospect, it’s not clear how many people would ever have been willing to do that, given that the authority of such a vote is almost universally accepted in the galaxy of Québécois student politics. But alas, it seems that, in the aftermath of those disastrous student assemblies, there was no one even able to bring up the idea to the hardly insignificant number of militants (student and otherwise) suddenly bereft of previous months’ democratic justification for continuing the fight.

Pursuing a hard line against nationalists and their discourse would also have divided and weakened the movement, but it would have publicized anarchists’ position on the Parti Québécois in clear terms. It would have offered an opportunity to call out their racist Muslim baiting in pursuit of the xenophobe vote, and their noxious valorization of French colonization on this continent. Had harsh critiques of CLASSE and/or ASSÉ come out when the strike was still in motion, rather than months later, this would also have divided the movement, albeit instructively. But if the movement is going to lose anyway, why not divide it?

It was clear after a certain point in August, if not earlier, that things were rapidly coming to a close. This was an inevitable result of the efforts of nationalists, social democrats, and others who had always been pursuing a conflicting agenda. Revolutionary struggle can be an ugly business, and there are times when it makes sense for us to hold our noses and work with people whose politics we consider objectionable. We should never attack or alienate those we dislike for no good reason. But, at the end of the strike, the benefits of making an open break were clear.

This is particularly important in light of the student movement’s unforgivable failure to support those who were facing judicially imposed conditions including exile from the Island of Montréal, non-association with friends or lovers, and the possibility of serious jail time in the future. It doesn’t matter whether the accused did what the state charged them with; the point is that illegal activity was essential to whatever success the strike had, and letting anyone suffer because the state pinned some of that activity on them sets a bad precedent for strikes to come. That’s the strategic argument, anyway—the ethical one should be obvious.

“The laws of the state and the batons of the police will not stop our revolt. Solidarity with those who face repression for their participation in the struggle!” This poster was wheatpasted widely in certain neighborhoods after the strike was over.

In short, anarchists could have done many things other than what we did do, which was to stay at the core of the movement. It was already clear by the weekend of the Grand Prix that the movement was on its way out; the events of June and July (or the lack thereof) confirmed this. Yet anarchists continued participating in general assemblies and committee meetings; to be precise, anarchists either returned to those spaces after having left them, or came to them for the very first time during the whole strike. This was done out of a mistaken belief that it was necessary to do so, that the struggle depended on the revival of the strike.

Depression and Demobilization

The end of the strike was marked by a pronounced failure to address the widespread phenomenon of post-strike depression. We might better identify this as post-uprising depression, common anywhere that has experienced sustained periods of social rupture.

Many windows opened during the strike, but now we find ourselves “between strikes,” as some people say here, which is to say in a period of demobilization. Compared to the spring of 2012, it feels unusually difficult to pull off even the simplest things.

Depression is an understandable but unfortunate response to the end of the strike. It’s useless, and a little cruel, to tell people that they shouldn’t feel sad about something that is an objectively depressing turn of events from an anarchist adventurist’s standpoint. Like any period of social rupture, the strike offered an exciting and dangerous context, presenting challenges to anyone caught up in it. To be sure, not everyone wants excitement, danger, or inconvenience. Many people would prefer to drive down rue Sainte-Catherine without worrying about giant demonstrations, or go to school without running into hard pickets, or take the métro without fear of a smoke bomb attack or bags of bricks on the rails. In contrast, the kind of person who’s going to become—and remain—an active, attack-oriented anarchist probably thrives on that sort of thing.

This is adventurism: the sin of actually enjoying the struggles we participate in. We may not all like the same things, or be capable of the same types of action, but our common thread—regardless of divergent physical ability, tactical preferences, skill sets, resources, and social privileges—is that we are fighters. The restoration of social peace deprives us of something we need. This peace is an illusion, and the social war continues, but it’s harder to position ourselves offensively when it’s no longer playing out in the streets every day and night—when thousands of people no longer see themselves as participants, having returned to the old routines of work or school or skid life.

There are lots of different ways to cope with depression. Hedonism is one way; after the strike ended, there was a heavy turn in some circles towards alcohol consumption, drug use, and hardcore partying. Another way is to switch gears entirely: some left town or put all of their energy into single-issue organizing, while others threw themselves back into school or art or earning money. Some of these means of coping were healthier than others. But as a whole, they all contributed to isolating people from one another and atomizing the struggle.

It was worse for the sizeable number of anarchists who stuck it out longer, trying to do exactly what they had been doing a few months earlier: going to demonstrations, mobilizing people for them, trying to hype people up and “make things happen.” After the electoral victory of the PQ, this simply didn’t work anymore. The problem wasn’t just that many anarchists had quit the strike by that time (although that certainly did have an impact). The problem was that anarchists in Montréal didn’t quit collectively. Instead, we quit one at a time, and often only once we had reached a maximum of exhaustion, a low of misery, or both.

Of course, it’s a stretch to speak of anarchists in Montréal doing anything in a coordinated way. There are simply too many organizations, nodes, social scenes, and affinity groups—each of which has its own distinct goals, outlook, and capacity. But none of these groups withdrew explicitly from the strike. Formal anarchist organizations in the city, except for a few propaganda outfits into heavy theory, had never fully engaged themselves in the strike as organizations.[5] It was individuals, usually working with others on the basis of friendship, who made the decision whether to drop out. The informal associations of people who worked closely together during the strike never met to discuss what people could do together as the strike was winding down. Consequently, these associations mostly evaporated with the strike.

There were many intentional discussions in June and July, announced ahead of time through social media and listservs, but most of these were focused on “the tasks at hand”—blocking the upcoming rentrée and continuing the strike. In my own circles, there was never time or space to talk about how people felt about the situation as a whole, how they felt about their own personal situations, or what they hoped to get out of continuing to engage with the strike. Nor were there many discussions between people who felt political affinity with one another, or who cared about maintaining positive relationships with one another more than they cared about abstract political objectives.

During the spring, we shared some incredible moments together. We flipped over police cars, partied in the streets, forced cops to run for their lives, painted the halls of university buildings according to our tastes, made out with strangers during street parties that became riots, and generally lived life to the fullest. It wasn’t all good, but the parts that were good were really good. Over the summer, like many other people, I made the mistake of attributing all that to the strike, rather than to the specific people who were in the streets acting to create those moments. The strike created the context in which those people were able to act together: it brought large numbers into the streets, it facilitated us running into each other over and over again, it frustrated and overwhelmed the forces that defend the capitalist economy.

But the strike had no agency of its own. It was itself the product of human agency—and by no means only the agency of anarchists. Although we were an influential minority in some regards, such as determining how confrontational the demonstrations were, we were not actually that important. Another influential minority consisted of careerist student politicians who were able to influence other aspects of the strike, like which images and narratives of the strike were broadcast on television and blogspace, much more effectively than we could.

Anarchists needn’t have been depressed by the end of the strike. This isn’t a macho admonishment that people shouldn’t let their feelings get the best of them; I don’t think the answer is for us to become coldly rational revolutionaries who move in a Terminator-like linear fashion towards our objectives. We are emotional creatures, and that is for the best. My criticism is that we staked our morale, our passion to fight, on the wrong thing: not on the health of the relationships of people seeking to be dangerous together, but on the health of the strike as a force that could interrupt capitalist law and order—which many of the people who created the strike never saw as a goal in itself, but only as a temporary means to a reformist goal.

As the strike was winding down, I should have dedicated more time to making connections with all those potential friends. There was one demonstration in August that I knew would be boring, but I went anyway. I saw someone there I’d seen a dozen times since February. He recognized me, too, and made a reference to the sort of thing we should have been doing. I laughed, but I didn’t keep talking—even though that was the last chance I’d see him. I should have introduced myself, tried to exchange contact information, and passed on an invitation to get together at La Belle Époque. It was my last chance to do that.

As for the people with whom I was closest during the strike—partners in the street, fellow writers of timely propaganda, and other co-conspirators—these were the people with whom I should have been discussing what would come after the strike. What did our experiences together during those months mean? As the larger movement fell apart, could that history of working together transform into something else?

But relationships between specific people were not prioritized at the end of the strike. Instead, we prioritized relationships to masses—which, it turns out, are much more easily seduced by politicians than by people like us.

Legacy

It took a few months after the election for things to pick up again—but they did. Struggle in Montréal can cycle quickly from highs to lows and back again. February of 2013 saw demonstrations first against the Salon des Ressources Naturelles, a reprise of the previous year’s Salon Plan Nord, then a major mobilization to oppose the PQ’s Summit on Higher Education, at which the new governing party confirmed that, rather than freezing tuition, they would index it to inflation and the cost of living. This was not a broken promise on their part; it had been part of their election platform.

SPVM forces move south along rue Berri on February 26, 2013.

Banner drop, March 5, 2013: “We demand not a free university but a free society. A free university in the midst of a capitalist society is like a reading room in a prison.”

Banner leading the march, March 5, 2013: “The social peace is behind us.”

The next month started off promisingly, with the night demonstration on Tuesday, March 5, getting a little rowdy near the Palais des congrès. Yet that was the end of this second cycle. On March 12, another night demonstration—albeit much smaller—was crushed before it even left Berri Square. On March 15, the SPVM, with the assistance of the SQ, crushed Montréal’s annual anti-police demonstration decisively. From that point on, all but one of the unpermitted demonstrations[6] that marched through downtown during the spring of 2013 were kettled and dispersed before they could become disruptive.

The police attacked the COBP demonstration on March 15, 2013 before the march was even scheduled to begin.

On the municipal, the provincial, and the federal level, the state has taken measures to prevent any reprise of spring 2012, passing laws to restrict or criminalize the essential elements of militant protest. The most ominous of these measures is Bill C–309, which finally became law on June 19, 2013. Applicable across the entire territory of the Canadian federation, it gives courts the ability to issue a prison sentence of up to ten years if a person is convicted of wearing a mask in the course of criminal activity during a demonstration. The simple fact of being present in an illegal demonstration can be considered criminal in itself.

Of course, actual police tactics are ultimately more important than codes and ordinances. The SPVM have evidently taken time to analyze the events of last spring, identifying their errors, drawing lessons, updating their old techniques, learning new ones, upgrading their equipment, and training officers. The results are plain to see.

In Québécois student politics, the reformist federations FÉUQ and FÉCQ have seen their influence reduced significantly, whereas the more radical ASSÉ (the kernel around which the now defunct CLASSE was formed) has more student associations affiliated with it than ever before. This is good for us, if only because ASSÉ’s direct democracy creates spaces in which it is harder to shut people up—and anarchists are precisely the kind of people that social-democratic politicos usually want to silence.

At the same time, ASSÉ is now disorganized and largely dysfunctional. The members who possessed revolutionary aspirations and the strategic ideas to match have largely abandoned the organization. There is good reason to think that, just as after the 2005 strike, it will take years before the organization is once again capable of mounting an effective challenge to the government. Whether or not anarchists choose to participate in that struggle (and some surely will, even if others don’t), it shouldn’t be taken for granted that the next social major upheaval in Québec will arise from the student movement.

Indeed, in the wake of 2012’s uprising, we should reconsider the strategies that have worked for us in the past. This is certainly true for all those who, in one way or another, sought to defend “the Québec model” over the course of the strike: the most significant student strike in Québec’s history, by just about any measure, didn’t even realize its most basic demand. For anarchists fighting in this province—and anyone else who would willfully jeopardize the comforts of welfare capitalism for half a chance at revolution and real freedom—it is incumbent upon us to determine how we should proceed towards our objectives, or live our politics, or both, in what is now a very uncertain political environment.

I will conclude with just a few concrete suggestions. First off, however we pursue our struggles in the future, we should strive to build more infrastructure, more formal communications networks, and more informal social networks that are autonomous of movements comprised largely of people with whom we have serious political differences. Doing this could make it possible that, the next time a large portion of society is drawn into the streets, we will be able to participate in the conflict without losing sight of our own values, building momentum that is not dependent on someone else’s movement.

Once we have infrastructure and networks of our own, as many anarchists in Montréal already do, we should be sure to use them. The thing that distinguishes revolutionary infrastructure from subcultural infrastructure—that is, an anarchist social center from a DIY punk space—is that, alongside its role as another space to live, socialize, and make ends meet, it should also serve to encourage people to throw themselves into anarchist struggle, and to spread the skills necessary for that task.

The latter first.

There are many practical skills that some anarchists already have, and others need to learn: digital self-defense, trauma support, tactics for street action, proficiency in different languages, and so on. These are all useful for specific situations—but we also need to be prepared for general situations. We need to be able to recognize when momentum is picking up, when we are at a peak of opportunity, when things are slowly or rapidly coming to a halt, and what is strategic for anarchists to do in each of these situations. Studying history, not just because it is curious or inspiring but in order to identify patterns and apply lessons, is essential if we hope to orient ourselves in the trajectory of the next upheaval to come.

Finally, the next time we realize that total anarchist triumph is no longer in the cards, we should consider the advantages of going out with a bang.

Further Reading

Report: Convergence for the Rentrée

For print: English | 8.5×11″ | PDF

For print: English | 8.5×11″ | PDF