Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

[For reading]

[For printing, 11”x17”]

“Direct action, simply put, means cutting out the middleman: solving problems yourself rather than petitioning the authorities or relying on external institutions. Any action that sidesteps regulations and representation to accomplish goals directly is direct action—it includes everything from blockading airports to helping refugees escape to safety and organizing programs to liberate your community from reliance on capitalism.”

– A Step-by-Step Guide to Direct Action: What It Is, What It’s Good for, How It Works

We believe that the greatest barriers to participating in direct actions are social ones: finding comrades to build affinity groups takes time, patience, and trust (see How to Form an Affinity Group: The Essential Building Block of Anarchist Organization). This recipe assumes that you already have people who you can get mischievous with.

Before we had ever done a night-time direct action, we felt hesitant to begin. We had no one to teach us the basics, and feared making stupid, easily preventable mistakes. For that reason, we want to share several logistical tips that we feel may be helpful in carrying out these actions.

Legal disclaimer: All information contained in this publication is for educational purposes only, and does not condone or encourage any illegal activity.

1. The secret is to begin

First, you need to choose the target of your direct action and what tactic you will use. Although this could vary widely, for this recipe we’ll use the classic example of smashing out the windows of a gentrifying business in an urban neighbourhood.

Think about what the action will communicate to people you’ve never met – from possible accomplices to the most passive citizen. What possibilities might this communication open up? For example, the numerous smashings of luxury businesses in Hochelaga and St. Henri over the past years have communicated a resistance to gentrification, have spread signals of disorder (see Signals of Disorder: Sowing Anarchy in the Metropolis) that visibilize how anarchists are fighting back against social control, and in some cases, have contributed to such businesses having to close up shop.

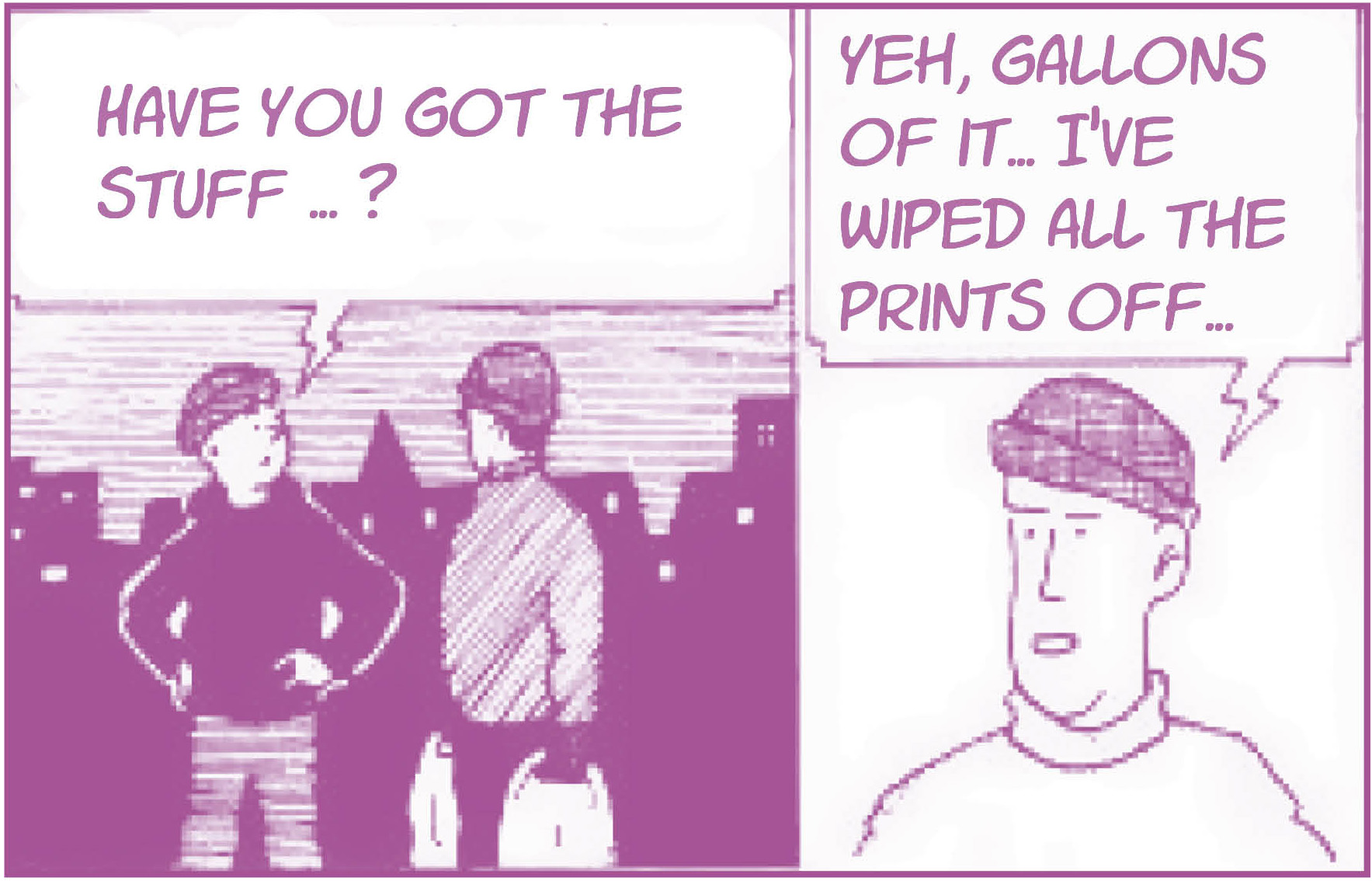

There are introductions to ‘security culture’ available elsewhere (see What is Security Culture?), but here we’ll just say to do all of your planning in person, with people you trust, outside of houses and with no phones present (both being vulnerable to police surveillance).

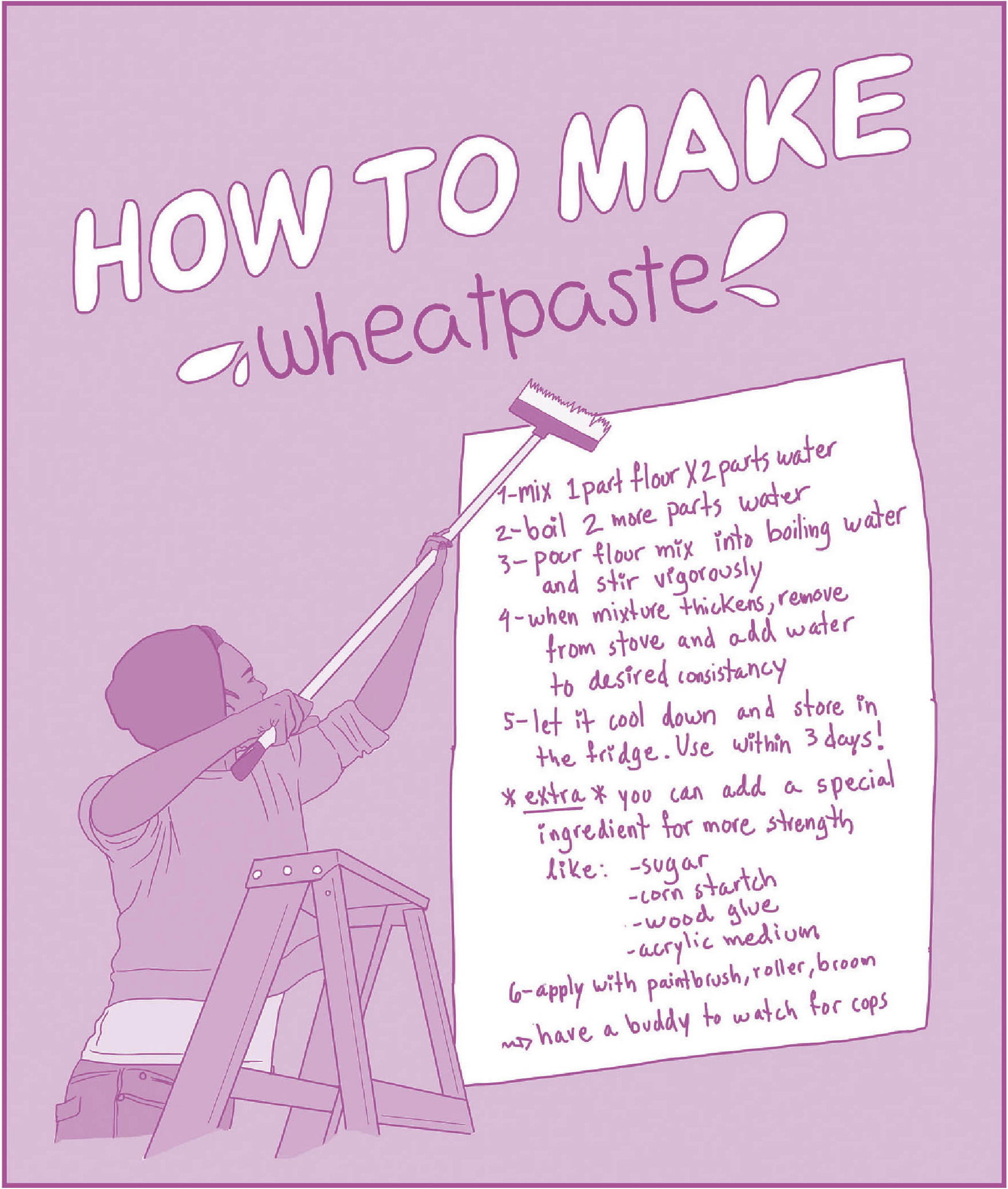

When we started getting our hands dirty, we found it helpful to first get comfortable with less risky activities like graffiti or wheatpasting posters, practicing the same communication habits we would later apply in attacks. This helps us become acquainted and feel more comfortable with our ability to act in stressful conditions (encounters with police, evasion, etc.) and our relationships with each other.

2. Scouting

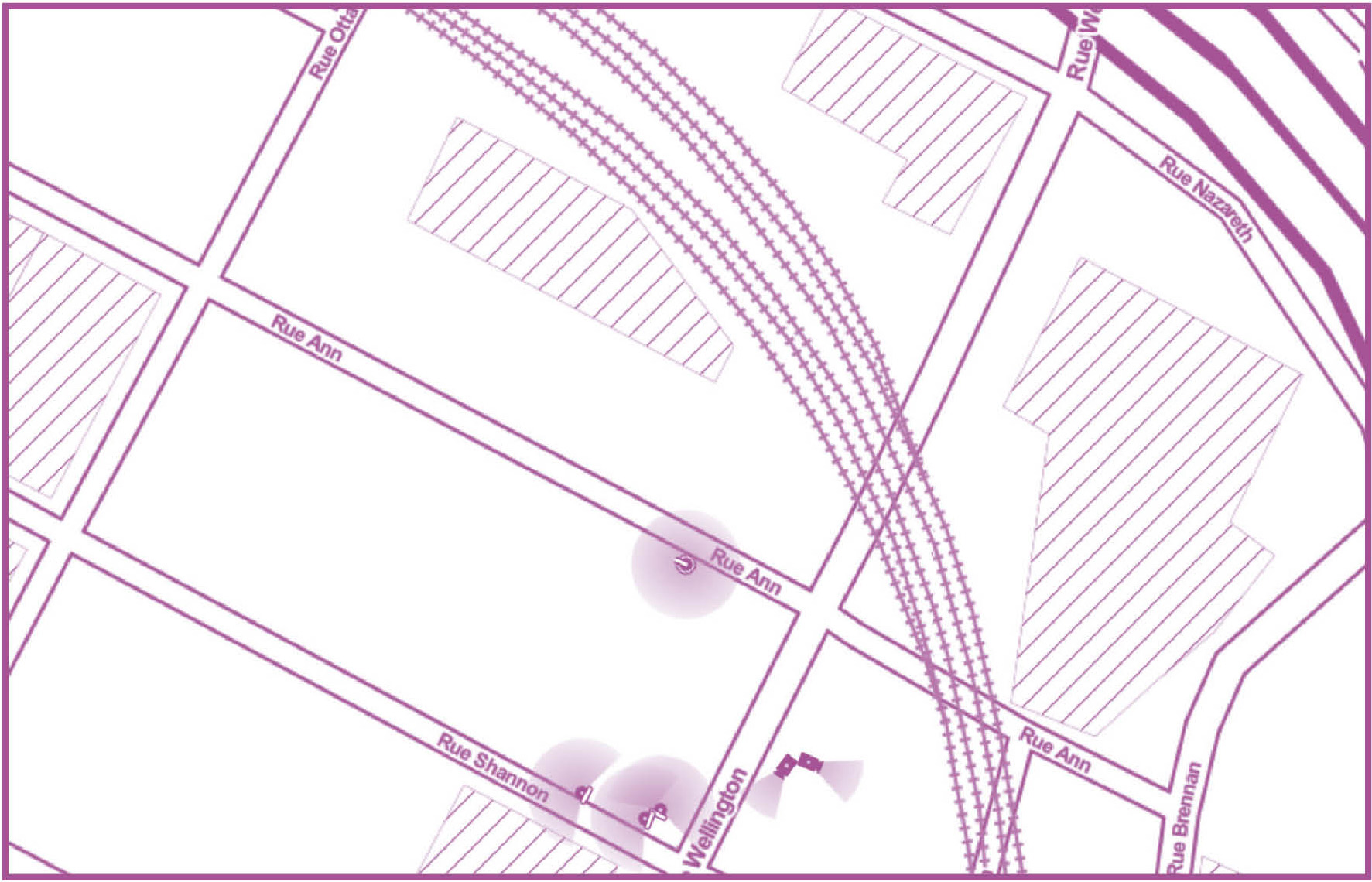

Scout the target ahead of time; look for the safest entrance route and exit route, prioritizing paths with fewer cameras (alleys, woods, bike-paths, train-tracks, residential areas). If you use bolt-cutters to cut a hole in a fence, will that open more possibilities? Have fun subverting the urban organization of space designed for social control to your purposes of social war.

Be discrete; don’t point at the cameras you want to smash, or walk in circles around the target. Decide where to position lookouts (if you think you need them), posted up smoking at bus stops that aren’t on camera, for instance. How will they be communicating with those doing the direct action: hand signals, inconspicuous shouts of random names to signify different situations, walkie-talkies, flashlights, burner phones (see Burner Phone Best Practices)?

It helps to know what the traffic patterns are like at the time you’ll be acting. How busy is foot traffic? Where is the closest police station, and what are the most patrolled streets? Doing the action on a rainy night at 3 am means there will be fewer witnesses, but also fewer people to blend in with afterwards when police might be combing the area, so sometimes closer to midnight will make more sense. Once you’ve gained confidence in nocturnal actions, maybe you’ll want to experiment with day-time actions that are more visible to passersby and thus harder for the authorities to invisibilize, like the looting of the yuppie grocery store in St. Henri last year. Leave at least a week or two between scouting your target and the action because that’s the average amount of time it takes for surveillance footage to be overwritten.

3. Fashion decisions! (and other prep)

Wear two layers of clothing; a casual layer for the action that includes a hood and hat, and a different layer underneath so that you don’t match any suspect descriptions. Blend in with the character of the area; it doesn’t make sense to dress like a punk in a yuppie neighbourhood, but it does make sense to be in flashy jogging gear if you’re going to be running down a bike-path. Baggy clothing can help to disguise body characteristics. A hat and hood will keep you relatively anonymous during your approach – most cameras are pointed from above, so your face will be mostly obscured when you’re looking down.

You can pull up a full mask for the last few blocks and the action itself (see Quick Tip: How to Mask Up). Depending on the terrain and where cameras are located, you may afford to wait until right before the action to mask up to avoid arousing suspicion preemptively.

Expect to be seen on camera during the action. Don’t get too paranoid about cameras in the surrounding area – a standard CCTV camera has poor resolution in the dark, if police even bother to get the footage before it’s overwritten automatically. All surfaces of any tools you’ll be using should be thoroughly wiped with rubbing alcohol ahead of time to remove fingerprints, and cotton gloves should be used during the action (leather and nylon will retain your fingerprints on the inside). Do not take your cell phone, or if you must, remove the battery; it geo-locates even when powered off.

Make a plan in case a good citizen intervenes, or starts following you to call the police. Dog-mace has worked wonders for us, but if that feels too intense as an immediate response, being verbally confronted by a masked group is enough to deter most people.

4. It’s witching hour

Once lookouts are in their locations and they give the agreed upon starting signal, take a final glance around, and go for it! For breaking the windows of a gentrifying business, bring enough rocks for several windows, aim for the bottom corners, and make sure you’re finished up within, say, thirty seconds of the first crashing glass pane. If you also want to put glue in the locks, paint-bomb the sign (see Paint bombs: light bulbs filled with paint), pull down the cameras (see the tips in Camover Montreal), write a graffiti message (in blocky ALLCAPS to hide hand-style particularities), or anything else that’s relatively quiet, do this before you make a kerfuffle breaking the windows, or plan for an extra friend to do it simultaneously.

Ditch everything including your top layer of clothing at the soonest appropriate place along your exit route – cops have lights that will reveal glass shards on clothing (more of a problem if you use hammers than rocks). Find creative hiding spots ahead of time to ditch anything you don’t want found, but as long as your materials and clothing are free of fingerprints it shouldn’t matter. The exception to this is arson tactics, where DNA forensics are more likely to be used, in which case you may want to take everything with you in a backpack and dispose of it farther away.[1. A note on DNA forensics: a basic principle is to never touch (or otherwise contaminate with hair, sweat, skin cells, dandruff, saliva, etc.) anything you’ll be leaving behind, because unlike fingerprints, DNA can’t be scrubbed off. Surgical gloves (sold at many drugstores) used with ‘sterile technique’ (learned on youtube) can allow you to manipulate materials without contaminating them once they leave their packaging. This should be accompanied by securing hair under a tight-fitting hat or swimming cap, a surgical mask to prevent airborne saliva, and wearing a long-sleeved shirt you’ve never worn that goes under your gloves (or even better, painter’s coveralls used for mold and asbestos removal). Work on a raised surface so that you don’t have to be bent over your materials. Have a second person (taking the same precautions) drop materials out of their packaging and onto your ‘sterile field’ (you can use a newly opened shower curtain, for instance), so that once you’re sterile you don’t contaminate your gloves with packaging you may have touched. To transport your materials, seal them in a garbage bag.]

Ideally, even if you are detained by police on your way out, you’ll have nothing on you that they can use to connect you to the crime. Know your story of why you’re in the neighbourhood, or be ready to remain silent because if they find evidence to contradict your story, it can be used against you in court, while your silence can’t be held against you. When arrested in Quebec, you only have to give the police three pieces of information: your name, date of birth, and address (this may differ in other places; it may be useful to be knowledgeable of local laws before carrying out any illegal action).

Once you’re arrested, saying anything else will do more harm than good. After providing the above three pieces of information, you can repeat the following phrase: “I have nothing more to say. I want to speak to a lawyer”. (If things go south, check out How to Survive a Felony Trial: Keeping Your Head up through the Worst of It. In Montreal, get in touch with the Contempt of Court collective for help with legal representation.)

A typical police response (if there even is one – often times vandalism is only discovered the next morning) will involve police first going to the scene of the crime, maybe taking the time to ask possible witnesses if they saw anything, then driving around the surrounding streets looking for possible suspects. If you get out of the immediate area quickly, you’ll avoid all of this. Hiding can be a viable option if something goes awry and leaving as planned looks risky – backyards, corners of driveways, rooftops, bushes, etc. can all be helpful in waiting it out.

5. Sweet dreams!

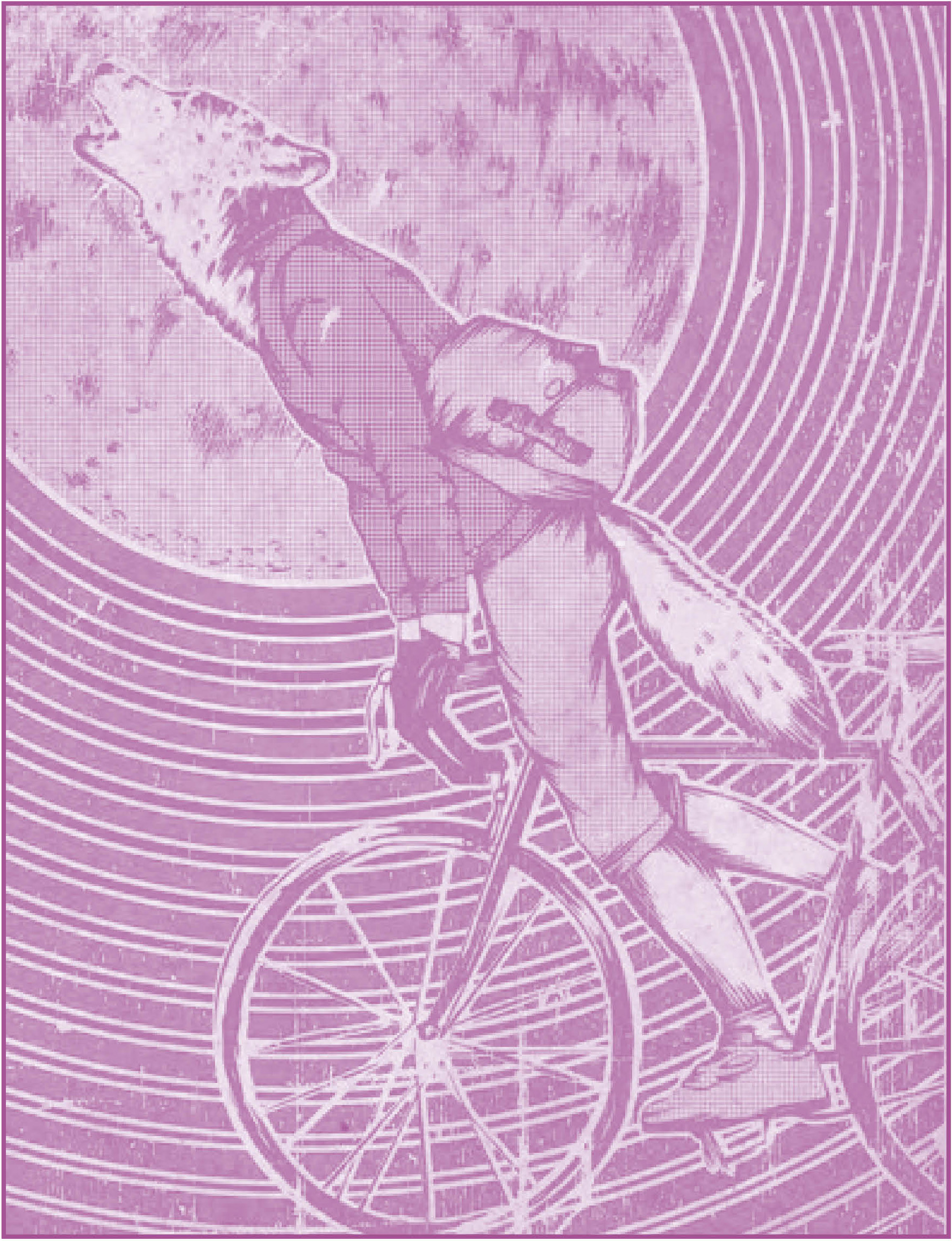

Consider using a bike to get out of the area quickly – you can have it locked a short jog away. Bikes can be disguised with new handlebars and saddles, black hockey-tape on the frame, removing identifying features, or an all-black paint job.

It’s best to avoid using cars if possible – a license plate is far easier to identify than a hooded figure on a bike. But if you must because the location is too difficult to get to otherwise, be careful. You could park a bike-ride away in an area that’s not on camera. Be dressed totally normally when entering the car. Take back roads and know your way around. Don’t use cars that may be already known to police, in case they have been tagged with a GPS surveillance device, and don’t use a rental (in part why Roger Clement got caught for arsoning an RBC branch against the Vancouver Olympics).

Rest well knowing that you’ve fucked up a small part of this fucked up world.

Check out How to safely submit communiques if you want to claim the action! Also check out this How-to page for more direct action guides: blocking trains, shutting down pipelines, demonstrations, riots, and more!