La Meute and Storm Alliance are two organizations which claim not to be racist, but which find their raison d’être in expressing (and spreading) fear of immigrants and Muslims, i.e. of “the other”, within Quebec. Both organizations are undemocratic, hierarchical, and operate within the far right range of politics that we could term national populist. Both aim their message primarily at conservative white francophone Québecois, of a similar set of social demographics (what one might think of as “good ol’ boys” and the women around them).

Despite the ideological similarities, SA and La Meute are in competition for the same base. This is a competition with important stakes, both in terms of stature/social-capital, and also certainly money, given the income from the sale of flags, t-shirts, decals, and other such merchandise.

For reasons flowing naturally from the larger/smaller dynamic, La Meute tries to insist on no double-membership, and discourages its members from backing SA. Storm Alliance, as the smaller entity, has nothing to lose from double-membership, and so pushed the “unity” line more, i.e. “we’re all in this together”. Indeed, unlike La Meute, Storm Alliance has no official membership, just officials in each region charged with holding meetings and organizing people to attend occasional protests.

Mainstreaming is currently a priority for La Meute. There is a clear alliance with the Citoyens au Pouvoir movement (formerly the Parti des Sans Parti) led by Bernard Rambo Gauthier, himself a La Meute member.[1] La Meute members could also end up being a significant bloc for the PQ or the CAQ, depending on how things go. Indeed, as a pressure group, La Meute will be most effective if it remains uncommitted to any one party, and as such courted by all.

Given this priority on mainstreaming, La Meute is attempting to clamp down on liabilities within their ranks, such as neo-nazis and other explicit racists. This is why they have disassociated themselves from a number of actions, and why they arranged for their official Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald to resign once his participation in the Charlottesville white supremacist protests became widely known. They are acting in a way familiar to many of us who are radicals on the left, as we’ve also been treated similarly by larger more image conscious “allies” of our own, those who hold large events and try to control which signs and slogans people bring, which discipline their members and have them all unite around the same line, etc.

As the challenger, Storm Alliance is forced to adopt a different approach than La Meute. As such, despite their repeated insistence that they are not racist and are not even against immigration when it is done “by the rules”, Storm Alliance remains far less skittish about the presence of open neo-nazis and racists in their ranks.

The entire relationship between these two groups is currently characterized by this lopsided competition. The only official collaboration they have had was on July 1 at Roxham Road in the small town Hemmingford, on the Canada/U.S. border, where roughly 60 members of both groups gathered to protest against “illegal” immigration. This was at a time when La Meute was still toying with the idea of providing security against antifascists for any group that asked, anywhere in Quebec (a predictably disastrous policy for a group hoping to mainstream, and one that was quickly and quietly dropped). Facing off against an equal number of antiracists who had been mobilized by Solidarity Across Borders, La Meute members sporting their own jackets and flags provided most of the foot soldiers for what was supposed to be a Storm Alliance event. Afterwards, numerous SA members expressed their displeasure with how it seemed La Meute was taking credit for the entire event, which had not even been organized by them.(Despite the equal numbers on both sides, everyone conceded that this was a victory for the antiracists, who won tactically by arriving in time to seize the actual ground on the border, essentially marginalizing the anti-immigrant protesters.)

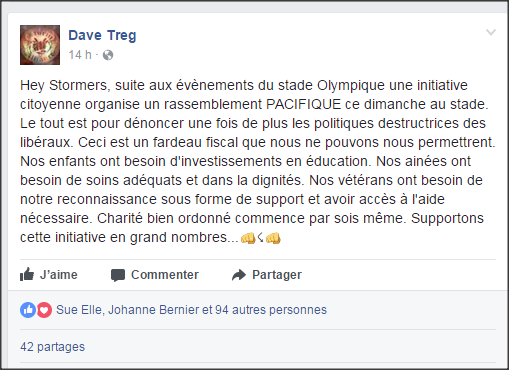

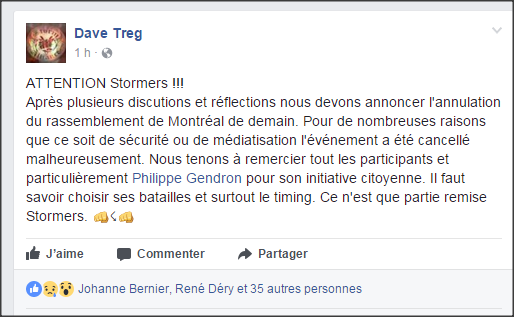

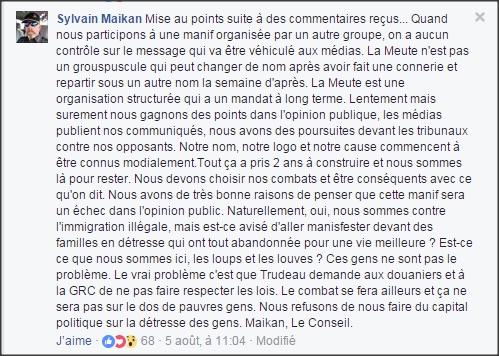

In late July and early August, La Meute’s main public activity was providing security for André Pitre, a far right vlogger, on his speaking tour throughout Quebec. Nonetheless, they were mentioned in the press (often in ways they did not like) as Pitre’s appearance in Rimouski was canceled, and when it was revealed that members of La Meute had been involved in the scandalous referendum in St-Apollinaire which ended up rejecting having a Muslim cemetery in that town. Storm Alliance was completely absent from these developments.In early August, Storm Alliance backed the idea of a protest at the Olympic Stadium in Montreal, where many refugees who had recently crossed the border were being housed. This protest was organized by explicit racists close to Storm Alliance and the Front Patriotique du Quebec, and despite their denials the intent was clearly to intimidate the refugees. True to its mainstreaming agenda, and despite initial enthusiasm from many of its members, La Meute quickly dissociated itself from the August 6 protest, going so far as to say that it would simply make people look like racists. This was a clear betrayal of their promise in the spring to provide security at any far right event in Quebec regardless of who was organizing it or why. Storm Alliance was left along with the FPQ backing a racist protest that was clearly going to be shut down by antifascists, as hundreds indicated on facebook that they would be attending a Solidarity Across Borders “Welcome Refugees” rally that day. Storm Alliance leader Dave Tregget was humiliated when the protest was cancelled, having to admit to his members that Storm Alliance could not guarantee their security. Storm Alliance allies Phil Gendron and Amber Dawson/Sue Elle/Sue Charbonneau were likewise humiliated, having to cancel the event.[2]

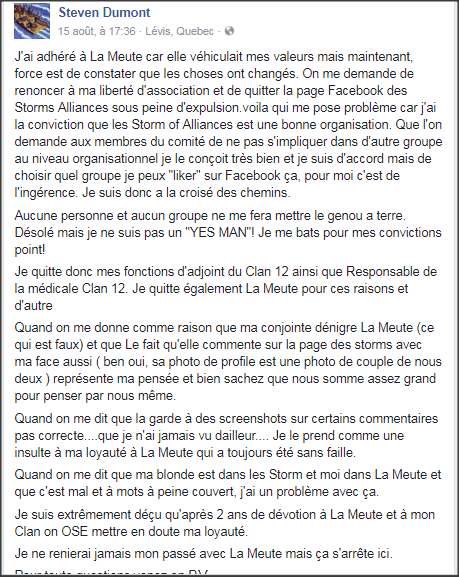

La Meute was criticized in some quarters for their “treachery” and “cowardice”. This coincided in August with a period of further tightening up on the part of La Meute, as members with official positions were expelled for belonging to the Storm Alliance Facebook group. See for instance the case of Steven Dumont:

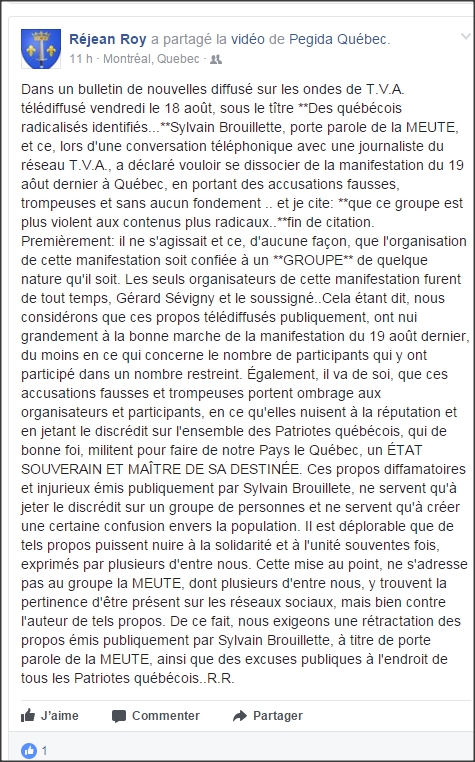

La Meute announced their August 20 demonstration “in support of the RCMP” in large part to reaffirm their bona fides as the largest and most important organization in the national populist milieu. This was to occur one day after an August 19 demonstration – also in Quebec City – that had the backing of the Front Patriotique du Quebec and Storm Alliance, again leading to complaints online about “divisions” and “lack of unity”. In response, La Meute clarified that it had nothing to do with the August 19 demonstration because of the risk that violent individuals would be present, and because without control over the slogans and signs, they might end up associated with racists or extremists. In this context, Storm Alliance played tit for tat, saying that while its members were allowed to attend La Meute’s August 20 demonstration, they were not to wear any SA insignia or bring any SA flags or signs. In the end, roughly 60 people gathered (unopposed) for the August 19 demonstration. The consensus seemed to be that it was a flop, and more than one participant expressed their anger on social media.

Two of those who did show up on August 19 were Storm Alliance leader Dave Tregget and Eric Venne (aka Corvus), the founder of La Meute who had officially left the organization in January (while in fact remaining a kind of roving “member at large”, in contact with different clans, and building up a kind of online following as a guru of the movement).The two men spent the day walking in the rain talking, and that evening Tregget posted a selfie taken with Corvus online and announced that his previous order was rescinded, that Storm Alliance members could now attend La Meute’s demonstration the next day in full regalia. It looked like a thaw – “for the greater good” – might be in the making.

It is unclear how things would have proceeded had there been no militant antifascist presence on August 20, but as it happened by the time Tregget and a few SA members showed up waving their flags, La Meute was already penned up inside an underground parking lot, unable to leave, and feeling under siege from the hundreds of antifascists blocking the main entrance to the garage. As such, it is unclear whether the word had been given to refuse Storm Alliance entry, or if this was just a result of the panic some La Meute security may have been feeling, but in either case that is what happened. Tregget and his people were turned away, in a situation where they would later complain their “lives were in danger” from antifascists. Another La Meute betrayal, as many on social media (and not only SA members) would put it.Tregget was in the somewhat pathetic position of always telling his followers that unity was paramount, that they should not disparage La Meute, and that everything would end up being fine between the two organizations – only to time and time again be treated like a two-bit flunky running some sideshow that not even his “allies” pretended to take seriously. No surprise that he and his groupies left straight from being rejected at the La Meute protest, to drowning their sorrows in a bar where they had to watch the action on television.

Indeed, regardless of the circumstances that led to this rejection on the 20th, within days it was clear that tensions between the two groups were not going to be patched over. Tregget may have made friends with Corvus, and may have been willing to bend over backwards to excuse and explain away the repeated rejections from La Meute, but this wasn’t going to be enough. On August 25, Eric Venneaka Corvus was expelled from La Meute, an act that he described as a “knife in the back.” Within 48 hours, he was back on social media announcing that he had been made an honorary member of Storm Alliance.

The dynamic La Meute and Storm Alliance are locked in is unlikely to abate, unless the former abandons its quest for legitimacy, or the latter accepts La Meute’s dominance and position as top dog. Even without being actively exploited by antifascists, these tensions will naturally provide us with some ammunition. An example of this can be seen in the case of Jean-François Dionne:

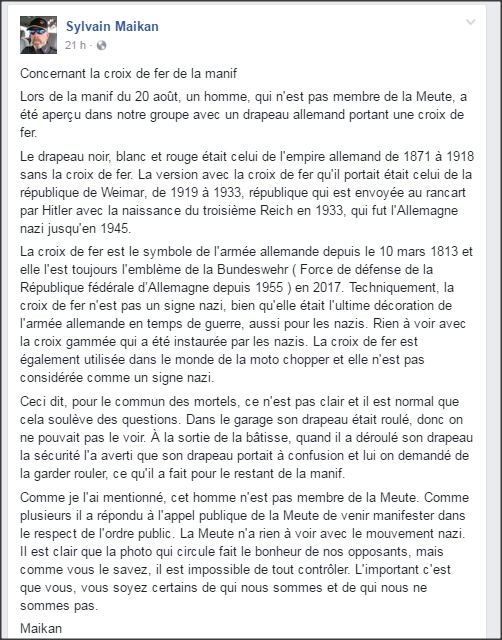

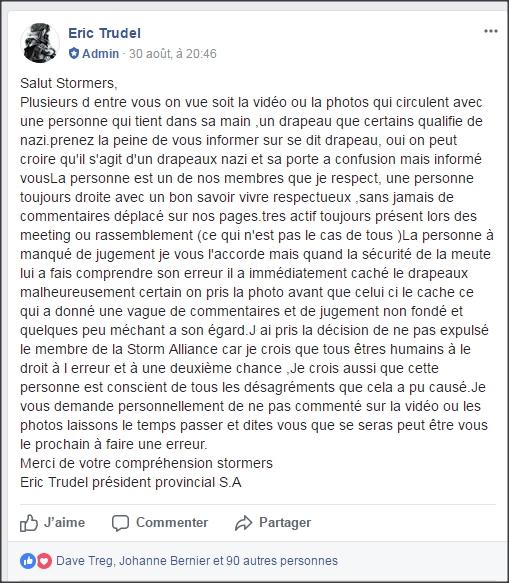

On August 30, La Meute’s spokesperson Sylvain Brouillette had to publicly distance the group from Dionne, who had attended their August 20 rally with an Iron Cross flag often associated with neo-nazis.

While Brouillette did not identify Dionne by name, other La Meute members on social media were quick to do so, pointing out that he was a Storm Alliance member who had also attended the August 19 demonstration and the July 1 action at Roxham Road. True to form, as a group whose only real appeal at this point is its willingness to accept neo-nazis and racists and anyone else in its ranks, Storm Alliance described Dionne’s bringing the Iron Cross to the August 20 demonstration as a “mistake” and explained that they had no plans to expel him.

The big test for Storm Alliance is coming on September 30. That’s the day the group has called a Canada-wide day of action to drum up fear and hostility against refugees and immigrants. Many of these protests will take place at border crossings, both for symbolic reasons but also in order to intimidate people crossing that day. In this context of open competition, La Meute has made a point of announcing – in the mainstream media as well as social media – that they will not mobilize on September 30, although they are not (yet) forbidding their members from attending. As such, September 30 will show whether the smaller group can in fact mobilize any real numbers under their own banner, and whether they can maintain their presence without the big bad wolf there to protect them. If they do, the next question will be, how much did they do so through reliance on even more hardcore racist forces, like the Canadian Nationalist Front, the Northern Guard, and other groups which have announced they too will be mobilizing that day?

A couple of things to keep in mind:

First, for our side: It is only natural that such divisions between our opponents should make us feel good, and to the extent that the pressure we brought to bear – on July 1, August 6, and August 20 – has played a role in this situation, we have something to feel good about. However, antifascists should remember that division and conflict do not necessarily signal disarray, they can also signal moments of clarification for political movements. For our opponents just as for ourselves.

We are in the midst of a series of unfolding crises, which are feeding into the underlying contradictions fuelling the growth of the far right, and of racist sentiment more broadly. While our opponents organizational woes are worth noting, and exploiting, they don’t represent any kind of deeper victory for our side.

And also, for the other side: If you’re a member of La Meute or Storm Alliance, you may not think much of us “antifa”, thinking as you do that we’re all living lives of luxury with our big fat George Soros cheques, as we plan white genocide. If you’re sincerely not racist, though, you must be asking yourself questions. In time you’re going to see that what you’ve been told about us is lies, and that in fact the problems this society is facing – poorly funded services for the elderly, a deteriorating healthcare system, cutbacks all over, and we all know the rot goes deeper than just that – aren’t going to be addressed by scapegoating Muslims or immigrants or anyone else, as the problem is capitalism itself, not some part of the working class that does not look like you or pray like you.

Maybe once you realize this, you’ll even come over to our side. But in the meantime, even if you remain where you are, we’re sure some of you are pissed off about these shenanigans between your “leaders” and organizations. We’d love to hear from you – we really appreciated the information you shared recently! – please let us know about what’s going on in your groups and how badly they are being run. Anonymity guaranteed! (we are not joking)

[1]http://www.journaldequebec.com/2017/08/11/bernard-rambo-gauthier-membre-de-la-meute

[2]https://montreal-antifasciste.info/fr/2017/08/07/6-aout-2017-plantage-epique-des-racistes-a-montreal/