First published at Real People’s Media

LIHT’SAMISYU TERRITORY – On October 17th, Lihkt’samisyu Chiefs Dsta’hyl and Tsebesa took action as Coastal Gaslink workers continued to trespass on Wet’suwet’en territory in violation of Wet’suwet’en laws and Canada’s own constitution. The Chiefs instructed Coastal Gaslink to remove all equipment from Lihkts’amisyu territory immediately, indicating that otherwise it would be decommissioned and seized by the Likht’samisyu Clan in accordance with its laws.

A video released by the YouTube channel Fireweed Solidarity shows Chief Dsta’hyl pulling up to a Coastal Gaslink worker who asks him, “What are you doing up on the road?” Chief Dsta’hyl replied, “This is our land. I’m allowed to be here, and you’re not. You guys are trespassing. I’m the Lihkt’samisyu security officer here as well as the enforcement officer. You guys are not allowed to be here. I gave you guys warning last year.”

The worker replied, “I know nothing about this” and Chief Dsta’hyl continued, “I gave all of you warning about this last year and I’ve got it all on video that you guys are not supposed to be here. I let everybody know that your equipment is going to be subject to seizure. We are going to decommission and seize your equipment. You can tell that to the head office and have them get in touch with me if you want.”

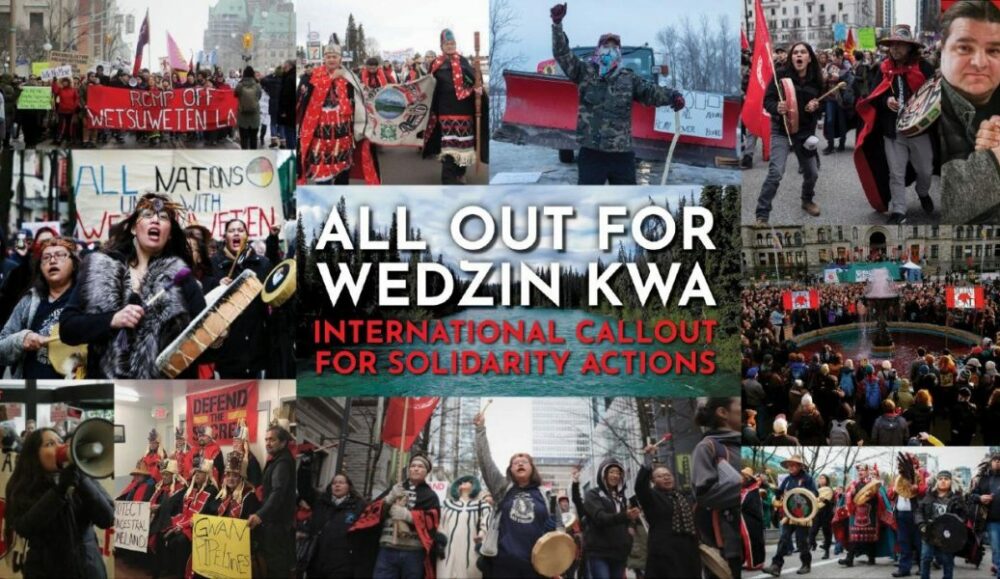

Coastal Gas Link has been damaging wetlands that flow to Parrot Lake, where the Lihkt’samisyu have reclaimed a traditional village site and established a community. The pipeline construction is the same one that the Wet’suwet’en people have been resisting for the last several years and which burst into national attention with the 2020 #shutdowncanada movement.

Equipment seized by order of the Lihkt’samisyu Clan Government

Later the same day, Chiefs Dsta’hyl and Tsebesa went to the location where CGL’s excavators were located and decommissioned an excavator. According to video of the incident released on the Sovereign Likhts’amisyu Facebook page, when the Chiefs approached CGL workers, Chief Dsta’hyl said, “I am the Lihkts’amisyu Enforcement Officer. I am asking you guys to all, please, leave.”

Chief Tsebesa stated, “Obviously CGL has never gotten consent from any of our head Chiefs or anything so this is the way our Chiefs are dealing with it. Like I said to you before; our law, our way. That’s all.”

Chief Dsta’hyl then proceeded to affix vinyl stickers to the side of the machine, indicating that it had been seized “By order of the Lihkt’samisyu Clan Government.” The CGL workers stood by and recorded the scene on video cameras without interfering.

Standing on top of the machinery, Chief Dsta’hyl addressed the workers saying, “We have to report back to the Clan Government in order to enforce the law. You guys are trespassing and we want to make sure that you guys know that we mean business when we say that we’re going to seize equipment from you guys. We are going to seize this piece of equipment and once we seize it, it is property of Lihkts’amisyu Clan Government. We’ll give you a chance to get it back and we will have the Chief Justice Hanamuxw here of the Gitsxan Court that will be proceeding with the court case for you guys. So it’s up to you guys to prove that you are not trespassing on Wetsuwet’en land.”

Chief Dsta’hyl then proceeded to decommission one vehicle, and stated that, “it’s the beginning of many that are going to be decommissioned over the next few days there until CGL moves all of their equipment off of Lihkts’amisyu territory. So it’s going to be really important there that they adhere to our message because we are basically governed under Gitsxan/Wet’suwet’en Law. So now what happens is our government is going to be looking after our interests ourselves on all of the land, logging, mining, and everything else that is on our territory and this is just the beginning.”

How you can support the Lihkts’amisyu

Donations can be made to support the struggle of the Lihkts’amisyu clan of the Wet’suwet’en at the groups Go Fund Me page. You may also contribute by e-transfer. E-transfer donations sent to likhtsamisyu@gmail.com will be deposited into a clan donation account with multiple signers. To find out more, visit https://likhtsamisyu.com/, and follow them on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/likhtsamisyu Twitter at https://twitter.com/Likhtsamisyu and Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/sovereignlikhtsamisyu/.