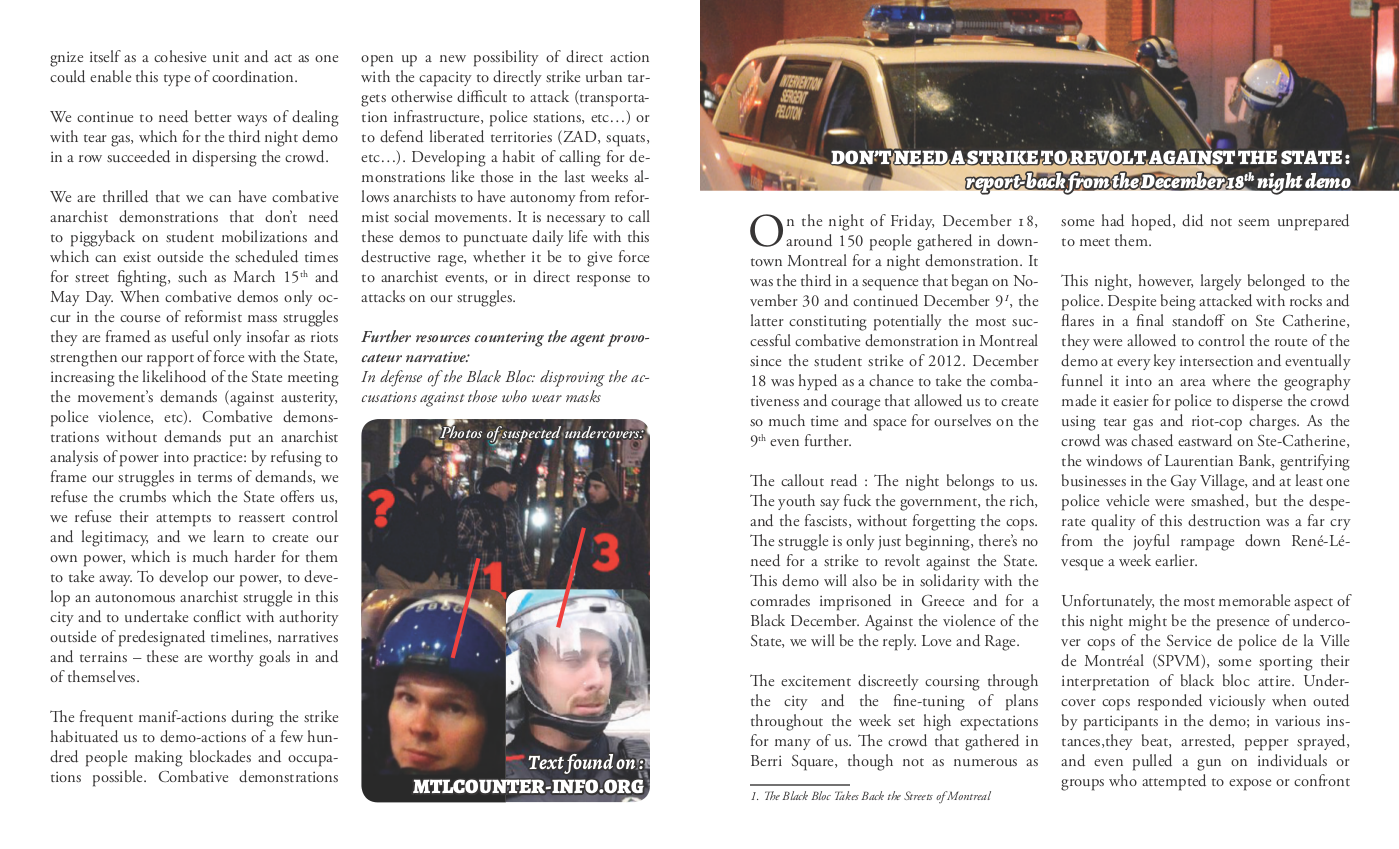

The Black Bloc Takes Back the Streets of Montreal

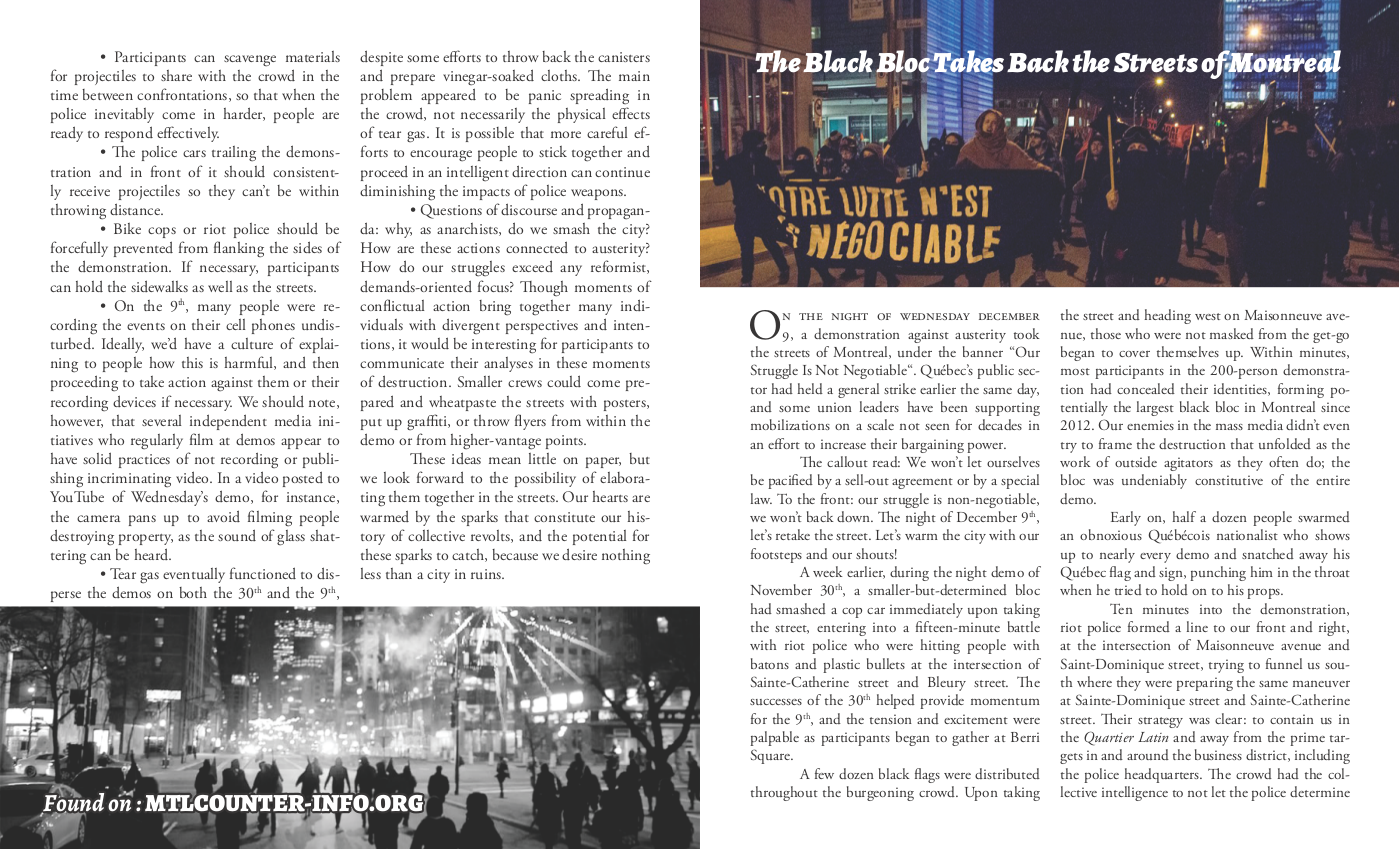

Solidarity with the struggle at Lelu island

Since late August 2015, Sm’yooget Yahaan, (the Gitwilgyoots hereditary chief of Lax U’u’la and surrounding waters) and his supporters have set up an occupation camp on his traditional hunting and fishing territory on Lax U’u’la (Lelu Island). This camp has been set up to assert title to his traditional territory, as Petronas and Pacific North West LNG are planning on building an $11 billion dollar liquified natural gas (LNG) plant on this traditional Gitwilgyoots territory, at the mouth of the Skeena river near Prince Rupert, BC. This plant will be fed by 3 LNG pipelines, including the recently provincially-approved PRGT, which crosses through Gitxsan territory, which is currently being met with resistance from the Gitxsan people through their Madii Lii encampment.

Who is involved?

The Petronas/Pacific Northwest LNG consortium which have proposed the Lelu Island LNG processing plant have subcontracted their environmental and engineering assessments to Stantec, Inc.

Natural Resources Canada has recently stated that the environmental assessments performed by Stantec on the island “likely underestimated” the environmental impact of the LNG plant on the Flora Bank. Stantec is currently attempting to continue environmental and engineering assessments, despite clear opposition from the Gitwilgyoots hereditary chief and the village of Lax Kw’alaams.

Stantec is also involved in several resource extraction projects targeted by Le Nord Pour Tous/Plan Nord. These include the Deception Bay Port Facility servicing Xstrata’s Raglan Mine and rail development for the Kamistiatusset Iron Ore Mine.

Fuck ’em

Montreal Offices :

300-1080 Beaver Hall Hill

Montreal, Quebec H2Z 1S8

isabelle.jodoin@stantec.com

T: (514) 281-1010

600-1060 Robert-Bourassa Boulevard

Montreal, Quebec H3B 4V3

300-1200 Saint-Martin Boulevard West

Laval, Quebec H7S 2E4

martin.thibault@stantec.com

T: (514) 281-1010

For more information & updates :

www.laxuula.com

https://www.facebook.com/Stop-Pacific-NorthWest-LNGPetronas-on-Lelu-Island-949045868451061/

www.flora-lelu.tumblr.com

The following flyer was distributed during the Trans March of Pervers/Cité (the “radical queer pride”) which had its route approved by the SPVM:

In the last two weekends in Montreal, two of the summer’s bigger queer parties have been shut down by the police (July 18th Cousins and July 25th fundraiser party for perverse/cite). In the first case, a large number of filth conducted an operation against La Vitrola forcing the organizers to finish the party and violently dispersing partygoers – there were numerous beatings and several arrests. In the second case (perverse/cite), one car with two officers successfully ended the fun by threatening people with individual tickets; the response by queers at the party was dismal, lacked solidarity, and in the writers of this article’s opinion was ‘unqueer’ (we’ll explain what we mean by this later). Despite the efforts of some agitators to hand out face masks, the party was swiftly shut down and people drifted off into the night. These attacks by police are only one of many forms of violence against queers, but they are one of the most easy to fight back against since they are attacks on large groups of people; if we take collective action, we can resist and we can win. Below are some reasons why we cannot sit back and let these things happen, we hope they will encourage you to take a mask next time someone offers you one.

Premise 1: You have to take what you need by force.

Repression is nothing new to the queer community, but inaction in the face of State violence has never been and should not become the legacy of our milieu. From the historical battles of Compton’s Cafe riot and the Bash Back blocks at the Republican and Democrat conferences to the contemporary struggles of Washington DC’s ‘Check It’ “gang” and the so called “Gully Queens”, LGBTQ+ people have a rich history of self defense, collective action, and militant antagonism against the State and those who would commit violence against us. We should feel honored to have and obligated to defend this legacy. More than that though, we see in these struggles, riots, and defenses of space the acquisition by queers of greater protection, better material conditions and more fulfilled existences; without these struggles we would be even more vulnerable to violent transgressions, have less/no access to hormones, and would be unlikely to have a Queer Milieu to exist in. If we don’t continue to struggle against police incursions into our space, we will lose what little we do have.

Premise 2: Being “Anti Oppression” means fighting the police.

Montreal’s queer community appears on paper to be committed to “anti-oppressive” politics and “safer space”; to this end, commitments towards changing our language, behaviors, and interactions with others are an important part of combating fucked up systems of oppression such as sexism, cisexism, trans-phobia, white supremacy, and classism, but personal behavioral changes cannot be the limit of our anti-oppressive politics. The gang known as the SPVM are one cornerstone of racist, classist, trans-phobic, and anti sexworker oppression within our city, maintaining social peace through violent repression, kidnap, murder, and theft. For many queers living here they pose a greater threat than someone getting our pronouns wrong or saying something trans-phobic. Especially if you are white, cis, middle class and/or not a sex worker, you have a duty to keep space safer by not letting the police enter, by refusing to allow them to interfere with events, and by actively interrupting their everyday activities. Standing quiet in the face of police attacks bolsters the arguments for “policing by consent”, makes individual police officers feel safer, and encourages cops to greater acts of violence against the most vulnerable people. To be anti-oppression means to be anti-the police; it might mean getting hurt or going to jail, but for many queers that’s already a reality whether they actively attack the police or not. If you leave a space as soon as the police arrive you are actively making that space more dangerous for other people. Sometimes you might decide that’s necessary for your own well-being, but most of the time it’s safer for everyone to stick together. It’s pretty hard for the pigs to arrest 200-300 party goes, but it’s easy for them to arrest 20-30.

Premise 3: Queer as a position of Social War ¹

Gender and sexuality are coercive and oppressive forces enacted upon us by society; without society, without social war, we wouldn’t have the conceptions of gender and sexuality (and the roles that they enforce) that we do. To attack society’s notions of gender and sexuality and attempt a radical transformation of them (i.e to be Queer) is to choose to engage in a very specific front of social war; to draw a line in the sand and open hostilities with the rest of society. If queers stopped drawing this line, then they wouldn’t be queer anymore; queer can’t exist except as a negation of enforced genders and sexuality. If queer identity is assimilated into the social project then Queerness will become just another oppressive mechanism. Part of the police’s role is to defend and protect normative articulations of gender and sexuality as well as to defend “society” at large; we are obligated by the definition of Queerness to actively engage in conflict with the police. In not fighting the police we are defending the existing paradigms of gender and sexuality and actively repressing Queerness.

Premise 4: It’s Fun!

Never mind getting drunk and dancing till your feet hurt, the raw joy experienced by fellow combatants in street conflicts with the police is something your dealer wishes they could market! If being queer is about forming new kinds of exciting, strange, and meaningful interactions and social relations, then what could be more interesting, exciting and strange than actively dismantling the State hand in hand with your new date/s; than breaking windows together, dancing atop a ruined cop car and running away into the night to make joyous criminal love. We don’t want to over-glamorize conflicts where friends get hurt, but fighting together and winning is one of the most exciting, joyous and liberating experiences these writers have ever had. Wouldn’t it be fun to chase the pigs off streets that belong to us and turn the whole fucking road into a queer dance party?

This communique was written by “The Angry Trans Mob”, we’re a crew of trans people from different backgrounds, struggles, and experiences who see the need for the expansion of conflict between Montreal’s queer milieu and the police/State/transphobes. We stand in solidarity with all those fighting to defend their communities (be those physical spaces/districts/towns or metaphysical ideas/identities/formations) from domination, attack, and destruction regardless of the weapons they choose to employ. We hope this communique inspires others to action.

And remember kids, ‘dead cops can’t kill!’

1) Social war refers to the conflicts waged everyday against our bodies by capitalism, the State, and the police, as well as by our friends, families, lovers, and ourselves. It is a way of describing the violence of all existing paradigms of reality/social relations and the struggles to change or destroy them. Positions within social war are constantly shifting insofar as individuals constantly, simultaneously and interchangeably embody the roles of oppressor and oppressed. Lines of conflict are drawn throughout physical and immaterial reality, and manifest as everything from the moment a doctor decides the gender of a newborn baby, to throwing bricks through the windows of a bank, to even the project of constructing the “human” subject.

Some Clarifications, thoughts, and rebuttals

▼ When we talk of fighting, we want to clarify we don’t think of fighting as inherently violent (not that we oppose violence) or necessarily as taking violent action (which we support). We think of fighting as anything from non-compliance, to staying close and solidaritous to prevent targeted arrests, to molotoving a police car; we don’t think everyone should be prepared to do all of those things but we do think people should be prepared to support and enable them.

▼ Space for us is not just a particular party or event, space extends physically and immaterially around and along any line that people call queer, from personal identity to physical locations. The milieu is a “space”; to this end we think that many “spaces” can occupy one location e.g. When defending a certain party from police incursion one is defending both the location and space of the party, but also queer space as concept, and milieu space as a formation. For these reasons, we think that the defense of every and any queer location (be that cousins, the queer book-fair, a sex party, etc.) is essential in order to maintain the concept of queer space which acts as a safety net for some of those most targeted by repression. An attack against a queer party is an attack against queerness; if enough parties are shut down the amount of space queerness occupies will be reduced.

▼ We are against the discourse that certain Diasporas of people cannot engage in conflict because of oppressions they experience or dangers that they face. While we completely support any individual who feels they cannot engage due to issues of status, race, class, gender, etc., we think that narratives such “certain people can’t do x…” are often infantilizing, untrue, and patronizing. While we should never expect anyone to be prepared to act in a certain way (unless they want to), we should not presuppose people’s abilities for them; all over the world people in precarious situations struggle (often illegally) despite the cost that they might incur. It is just as true to say, for instance, that a demonstration which has been approved with the police is likely to make people feel unsafe as one that is declared illegal – if you don’t know people’s personal histories, you don’t know whether seeing demonstration organizers collaborate with police might feel more unsafe than being at an illegal demonstration. Moreover, collaborating with the police because a demonstration is not likely to do illegal things or to make certain people feel safer may further isolate people whose lives and existences are inherently illegalized. The hierarchies of danger established by the milieu should be constantly contested and debated.

▼ We reject the idea that violent resistance is inherently and exclusively white and male; we think this position is often used to delegitimize tactics that don’t fit into certain people’s ideas of acceptability and is sexist and trans-misogynistic as well as historically inaccurate.

▼ Although we firmly support self-identification, we reject postmodernism and the idea that anything can be called queer. We believe that queer is a positionality connected to other positionalites (such as race or class) and that there are certain limitations to what and who can be considered queer (just as a cis person cannot be trans, and a self identified trans person cannot be cis). For example, we think that a police office cannot be queer, because the role that they take in enforcing existing gender paradigms is contra queerness.

By writing this text, we want to open lines of communication and critique regarding anarchist practices in the streets of Montreal, on a tactical level. We continue to see the same mistakes being made in demos and attribute this to how reflection on these matters rarely goes beyond the reach of affinity groups. We feel the limited amount of new information the police can gain from reading these general reflections is outweighed by the possibilities that can arise when we are better able to act as a collective force in the streets. It is our hope that others feel impelled to further these discussions within our anarchist networks, both in the form of anonymous texts and in the relationships they hold dear. Here are some reflections from three affinity groups, which will only be of value if we bring them to life in critical discussion and practical application.

Struggle in the streets of Montreal seems to be at a transitional phase. Over the last year, many people have learned to overcome their fear of the police, and this translates into a heightened spirit of combativeness in demos. At the same time, our ability to confront the forces of order has progressed less quickly, so that our enthusiasm often outruns our material capacity to fight. With greater self-organization, comrades who share affinity would be able to better clarify goals and intentions, to hone plans, and to share skills and tools useful to confrontation. Police commanders continuously reflect on crowd control and adapt to changing conditions, and we must respond with tactical developments of our own.

A typical demo in Montreal involves masked individuals scattered throughout the crowd – sometimes in groups, sometimes alone, sometimes hanging out with unmasked friends – who only rarely attempt to communicate or be in the proximity of other groups. Those dressed in black may be referred to as “the black bloc”, but it is not a bloc at all. Blocs consciously stay tight in order to have each other’s backs, and they collectively work together in anonymity to realize shared intentions.

We attribute the prevalence of masking without clear intent to a fetishization of the black bloc tactic, in which the masked aesthetic is valued in and of itself, even in the absence of the revolt that masking up is supposed to facilitate. Or, perhaps paranoia and social awkwardness are barriers to communicating with unknown comrades, and hence people remain isolated. We all have to break through these communication barriers in order to sharpen our struggle together, to respond quickly to opportunities with force. All too often, a few stones are thrown in isolation as a symbolic gesture before a dispersal that the crowd is unprepared to repel.

The goal of engaging in confrontation has to be clarified and discussed; for us, it is to free space from police control, which we see as a prerequisite for anything interesting to follow. Ritualistically smashing a bank window without the capacity to push back the police will often, predictably, cause the demo to be attacked and dispersed. Such one-off attacks do little to build our rapport de force in the street and our capacity to sustain struggle, to take and defend space. Our attacks should be practiced in a way that collaborates with the larger demo instead of using them as cover without regard – or an ability to respond – to the consequences. Instead, we can concentrate forces on targeting the police, seeking to make them retreat and break their control over the crowd. Having done this, we can destroy all the capitalist property we want, without leaving the rest of the demo to bear the brunt of the police crackdown brought about by our all-too-brief actions.

Anonymous impromptu spokes councils.

Reflections on informal communication in demos.

Lines of communication should be opened in the section of the demo that is willing to be confrontational. One form this could take is an anonymous impromptu ‘spokes council’. One person from each group could huddle to discuss general strategies and plans that make sense to be shared. This spokes council could re-form at any crucial point during the demo to make more collective decisions impacting all those who want to fight.

An example of this occurring very successfully was during the G20 in Toronto. The black bloc – which actually functioned as a well-organized bloc – had a spokes council during a crucial moment after trying to head south to the guarded G20 perimeter and being pushed back with batons. The spokes council contributed to the bloc sprinting east away from the perimeter and through the downtown core, confounding police expectations, and leading to over an hour of heavy rioting and two torched cop cars.

This is but one example of how we could improve our communication in a well-organized bloc. It’s not a panacea, spokes councils can be difficult to put into play. Often, shouting slogans (“to downtown”, “stay grouped”, etc.) will work just fine. But if we want to better coordinate ourselves, we must reflect on more effective means of communication.

Dealing with the Urban Brigade

One of the SPVM’s most notable crowd-control adaptations has been to flank the left and right sides of the section of the demo they deem most likely to cause trouble. At least sixteen unshielded police walk on each sidewalk, with at least one rubber-bullet gun, usually in the middle of the line. During May Day 2012, when they flanked only on one side, we saw how the bloc did not have the confidence or organization to offensively attack them. As a result, they were able, at the moment of their choice, to cut through the demo when we were vulnerable and make arrests before retreating on Ste-Catherine. The Urban Brigade will always act at an intersection so that they can retreat on a street that demonstrators aren’t occupying. They will then keep the crowd at bay with rubber bullets while they complete their arrests. A new addition to this tactic has been to position horses at the rear of both brigades, generally three on each sidewalk. They play a double role: intimidation and being above the crowd to identify targets for eventual arrest.

Interestingly, on February 25, 2013, during the first demo against the Summit on Higher Education, after months of these flanks successfully controlling demos, the crowd had the collective intelligence to fill the sidewalk behind the left flank, trying to force them out of the demo. If we refuse to yield the sidewalk to the Urban Brigade, this new tactic which has so far been very successful at policing us will be largely compromised. Those who took the sidewalk were not materially prepared for the close-quarters confrontation that must follow from this assertion of space (apart from several paintbombs), so the police were able to hold their ground. They nonetheless needed the brigade that was on the other sidewalk to break the encirclement. One intersection further down, the Groupe d’intervention unit (GI, riot police with full armour and shields) was waiting to charge the demo, throwing at least two flashbombs.

If there had been a tight bloc with different groups in communication with each other, and with reinforced banners to the front and sides of the bloc backed up by long flag poles, this confrontation could have gone further. Of course, once we rid ourselves of the Urban Brigade, the actual riot police will be put into action, but we will have at least made ourselves less vulnerable and increased our chances of successfully confronting the other police forces (including the undercovers). That said, once rioting has kicked off and police begin dispersing, it can make a lot of sense for groups of 10-20 within larger splinters of the demo to keep doing their own thing, making the situation that much more uncontrollable.

This brings us to the question of material brought to be used during demos. Lately, we’ve seen people self-organizing to bring side banners that have greatly impaired the capacity of the Urban Brigade to act. This practice should become systematic. The cops responded by placing horses on the sidewalks; we must think of ways to get rid of them. The better we are prepared to face the Urban Brigade, the less danger it will be to us. A group of 10 people with flagpoles backed up by rocks would be sufficient to push back the Brigade, but not the GI with shields.

Behind the barricades

The construction of barricades and defence of occupied spaces such as squares, parks or large intersections have barely been attempted during the past year, despite all the opportunities we have had. We should experiment with holding space in ways other than the long procession of the traditional demo, which is relatively easily for the police to cut into pieces (cutting the demo in two is even the first step in the dispersal process used by the SPVM). For instance, if a square is filled with demonstrators who are unwilling to abandon their comrades, and the main entrances are all barricaded, police could be fought back for hours. Behind the barricades, we find the possibility of transforming the often fleeting and fragile nature of our attacks, opening up time and space for rebellion without an endpoint, to be elaborated with joy. We can see that this lesson has been learned during rioting in Athens, Barcelona, etc.

By barricades, we mean objects that can substantially impede police movements, like flipped dumpsters or cars that are bumped into both sides of the street by lifting and rotating the back (lighter than the front). The street signs and pylons that are used so frequently do more to impede our movements than police movements. They can even be dangerous for inattentive comrades.

If barricades can be made quickly when moments arise where we find ourselves in a fitting location (for instance, without too many entry points, with a significant amount of rocks that can be plied up from the street, construction sites nearby to be raided, parking lots offering ample cover as seen on April 20, 2012, around the Salon Plan Nord), we can hold our ground and fight from behind the barricades, obstructing the charges that have ultimately dispersed us successfully at every demo to date.

Returning to the example of last May Day, at the corner of University and Sainte-Catherine after the Urban Brigade was fought back with projectiles, we all knew that the GI would arrive any minute in lines too heavy to fight back with only rocks. Many people busied themselves collecting rocks during these precious minutes, but no barricades were built, so when the GI unit came charging from the south, the demo was chased into undesirable territory north of Sherbrooke and forced to disperse.

We know that it is not easy to overcome the fear of repression, that some of us still hesitate to throw the first stone, and that is why we must be explicit within our affinity groups as to what each individual is ready to do. Some will prefer to gather rocks and distribute them to comrades who are willing to attack the cops. Some will be ready to hold the side banners, knowing that they might receive the first blows when the Urban Brigade decides to charge. And some will want to observe and analyze police actions to prevent the demo from being kettled.

In thinking critically about our street tactics and forms of self-organization, these are only a few ideas from some of us who by no means consider ourselves experts. We await other contributions toward this end, by those who prefer communicating through texts as well as those who will share their reflections through their actions in the streets.

In solidarity with those arrested during the strike.

Friday, Oct 26, 6:30 pm

Carré St-Louis, Sherbrooke metro

The strike is over. The PQ is now saying that we all fought together to overcome the tuition hikes and special law. The politicians are using the initiatives of people who actually lived that struggle to gain power and further their own careers.

Meanwhile many of those who participated in the strike, beyond drinking champagne and talking to the media in government offices, are still facing charges, conditions, and potential prison time.

There have been over 2000 arrests; over 500 people are facing criminal charges. Some people have lost their eyesight forever to police sound grenades; many others have tasted pepper spray and fought off batons. Some have had their houses raided early in the morning and spent time in jail before being released with suffocating court conditions.

One example is ‘non-association’ – ie. being forbidden from associating with anyone who has a criminal record or pending charges. In a context of so many arrests, this means just about everyone. Others have the condition to be a certain distance away from any school, to live with their parents, to follow a 9 pm curfew, and to not be in the metro. At least three people’s lives have been completely uprooted by the condition of not being allowed on the island of Montreal; they have been forced to leave their apartments, their friends, and their entire lives. They were and still are our comrades. Today it was them, tomorrow it could be us.

Repression – whether through conditions, Law 78/12, or the legal system more broadly – seeks to break up social struggles that threaten capital by trying to silence, scare, or isolate those who successfully challenge it, such as what happened during the student strike. The state, either through coercion (à la Liberals) or coaxing (à la PQ) has forced many back to school, trying to make them forget about the moments of freedom so dearly won during the spring. While talking about victory, it tries to erase those who fought the hardest from collective memory.

But they are not forgotten. We’re sick and tired of pompous judges deciding where we sleep, where we live, what streets we can take. We’re sick of the raids, the police harassment, and the legal system. Staying passive and doing nothing only legitimizes this repression.

What we need now is a fierce and active solidarity.

Refusing to condemn or dissociate from those facing charges, denouncing the criminalization of demonstrations, opposing targeted arrests and snitch culture, defending the legitimacy of anonymous participation in demonstrations by wearing masks, providing legal, financial, political and personal support to the arrested and forcing the state to drop their charges, taking care of those injured, supporting each other, as well as continuing, expanding, and intensifying the struggle of our arrested comrades – these are the foundations of a culture of struggle that we need to build and develop.

A struggle is nothing if it forgets its prisoners.

Let’s come together in the streets, express solidarity with all those who have faced repression in the strike or elsewhere, and show our comrades that we are with them.

Halloween costumes and masks encouraged!

It’s clear that this is no longer just about tuition hikes. The tuition hikes go hand in hand with new user fees for health care, and rising rents, food prices and electricity rates. The tuition hikes come in the context of condos taking over our neighbourhoods, evictions and expropriations for the sake of “development”, immigration officials deporting our neighbours, cops shooting people in the street, and the imprisonment of friends and loved ones. Austerity measures are coupled with increasing repression. Law 78, an attack on the right to organize collectively, is only the most recent example of this. Over 2500 people have been arrested during the student strike and some of them have been exiled from Montreal until their trials.

In May, rumours started to circulate about a social strike in the coming months. For many people a general strike happens through a union vote, but, for unions, a strike is illegal during times when the union is not bargaining for a collective agreement, and for others there is no union at all. So how do we strike against austerity and increasing repression, especially when our unions hands are tied or we have no union? And what the hell do we mean by social strike?

The student movement has been able to do what it has done because of collective organizing in schools. This spirit of collective organizing could spread to neighbourhoods and workplaces. One way that has been happening is through autonomous neighbourhood assemblies meeting to find ways to act together and build power outside of the government. Another way this happens is through collective workplace organizing without union approval, which can take the form of a wildcat strike.

Another way the student movement has been able to strike for so long is because of their willingness to take action to make the strike effective. Between targeted economic disruptions and picketing the universities, the students have been able to block bridges, stop traffic downtown, shut down their schools and more. What could this look like for us and our neighbours and co-workers? In St-Henri, neighbours marched to a disruption of the Grand Prix together. In Villeray, the casseroles joined up with the night demo downtown night after night. In Barcelona in March this year, people involved in a general strike barricaded their neighbourhoods, picketed downtown and shut down businesses.

We know that in August the government will try to force striking students to go back to school. Law 78 will likely be used to justify police attacks on students, criminalization, and heavy fines. The movement will require widespread support to fight back against these attacks. We believe the social strike can be an effective strategy for advancing the student strike, and resisting all austerity measures. When we organize ourselves to shut down our schools and workplaces, we demonstrate our collective power, and give ourselves the opportunity to act in solidarity with others who are struggling alongside us.

Lets do it!

On Friday, May 18, 2012, two new laws came into effect in Montréal. Their purpose is to stifle the anti-capitalist revolt that has grown from the more-than 100-day-old provincial student strike. The first is the municipal by-law that forbids the wearing of masks during any demonstration with the penalty of a $1000 -$5000 fine (additionally, if the Federal government’s proposed law comes into effect, wearing a mask in a ‘riot’ could result in up to 10 years of prison). The second is the provincial government’s Special Law (Loi 78) that requires any public demonstration to submit itself to meticulous control by the police to avoid being declared ‘illegal’. Any leader, spokesperson, or rank-holding member of a student association that blocks access to classes or counsels others to do so will be subjected to a fine ranging between $7000 and $35,000.

While these laws may be shockingly harsh, their appearance is not a shock in itself. Throughout the course of this struggle the state and its police force have already taken eyes, broken arms, shattered jaws, and put people into life-threatening comas. Yet thousands of us still fill the streets day after day, hoping to maintain a struggle with teeth. These laws are the logical outcome of a situation that has surpassed the control of general assemblies, student federations and government authority. Loi 78 has been declared ‘anti-democratic’ by legal groups such as the Québec Human Rights Commission and the Bar of Québec. Yet we know the government will do what it wants. Democracy and the liberties often associated with it are fed to people in times of social ‘stability’. These laws show that as soon as we step out of line and create ‘unrest’, authoritarian repression strikes. The state of emergency is always around the corner, waiting to impose more control over our lives in the moments when we start to truly live them.

Laws, bureaucracy, and police came before democracy; they function the same way in a democracy as in a dictatorship. The only difference is that, because the right to vote exists, we’re supposed to regard them as ours even when they’re used against us. Democracy presumes that all power and legitimacy is vested in one decision-making structure, and it requires armed bodies (the police) to regulate, to control, to enforce these decisions. Knowing this, we fight for true liberation, not just a less-shitty politician in the same oppressive power structure.

Resistance must spread, evolve and continue indefinitely. We have watched the situation transform from a limited strike with reformist goals to a generalized revolt with revolutionary aspirations. It is not just about tuition fees. This system that increases the cost of education is the same that cuts pensions and welfare in the name of austerity, turns forests to concrete and lakes to oil spills in the name of progress and industry, kills entire communities in the name of security and patriotism, and views lives as expendable in the name of profit. Capitalism and the state must be combatted in many ways.

Banging pots and pans in our neighbourhoods every night at 8pm is one way to do so, as well a way to build neighborhood cultures of resistance and start to form social relations outside the walls of isolation built by this society. But we must remember that power does not concede when simply asked. Even Finance minister Raymond Bachand approves of these casseroles demos, stating that they are festive and ‘send the right message’. In an effort to divide us into ‘good protestor’ and ‘bad protestor’, he wants to keep people’s participation pacified and business-as-usual continuing in the city. But we know that diverse and confrontational tactics will not only empower us to begin to act in this world on our own terms, but also to create a force to be reckoned with…

A force the state can no longer ignore!