From Montréal Antifasciste

Using the pseudonym “Neuromancer,” Alex Liberio was one of the neo-Nazis active on the Discord server and in the Iron March chatroom, as well as an engaged participant in the activities of Montréal’s alt-right from early 2017 until January 2018.

In May 2018, the tenacious efforts of Montréal antifascist militants led to the exposure of a an alt-right chatroom on a Discord server meant to serve as the launching pad for the “real-life” activities of a group of militant neo-Nazis in the Montréal area.[1] A series of articles published in the Montreal Gazette forced two of the key organizers of the group into exile: Gabriel Sohier Chaput, alias “Zeiger,” and Athanasse Zafirov, alias “Date” (also sometimes “LateOfDies” or “Sam Houde/Hoydel”). Zeiger was not only a central figure in this little Montréal-based group but was also part of an international network that developed from 2015 to 2018; notably as a prolific producer of content for The Daily Stormer website, as a moderator of the Iron March chatroom, and as a key propagandist for the explicitly National Socialist and accelerationist tendency of the alt-right movement. There is a warrant for his arrest in Québec, and he is currently in hiding. Meanwhile, “Date” (or “LateOfDies”), who seems to have been gradually radicalized, beginning in the “Pickup Artists” scene personified by the misogynist Roosh V, was a key organizer in the local and national alt-right milieu; exceptionally as a leading organizer of the pan-Canadian gathering held in Ontario in July 2017. He relocated to California in 2018, where he is comfortably ensconced in the doctoral program at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management, in spite of our article that exposed him and his new life.

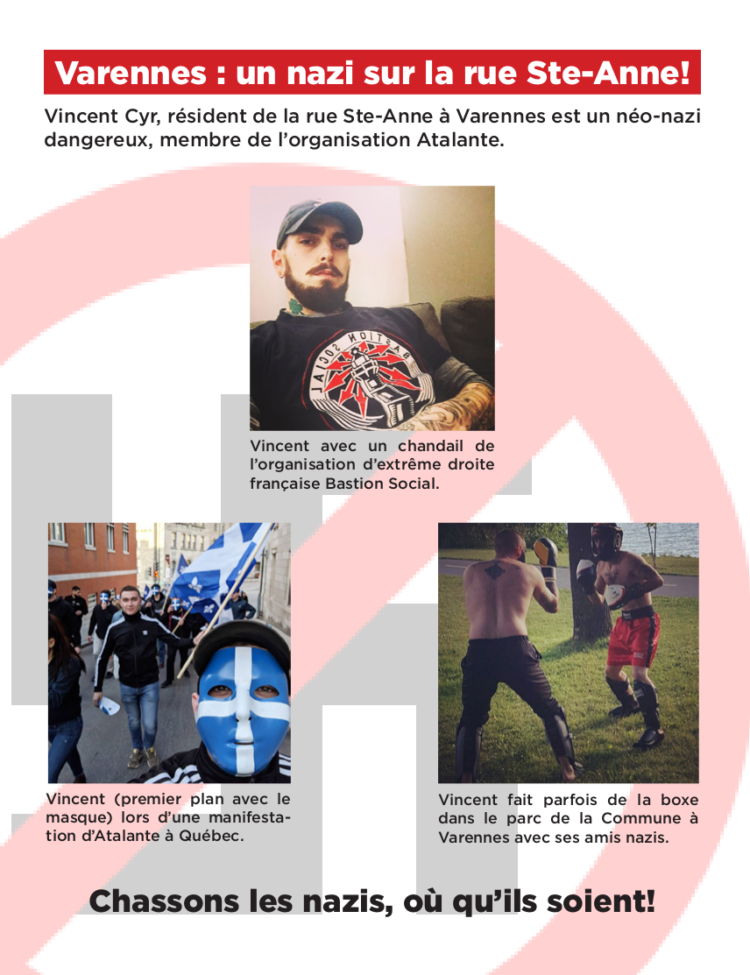

Three other notorious militants from this little group were also unmasked by the antifascist community, including Shawn Beauvais MacDonald, alias “FriendlyFash” (or “Bubonic”) and Vincent Bélanger Mercure, alias “Le Carouge à Épaulettes” (or “BebeCoco”), both of whom participated, alongside Sohier Chaput and other Canadian far-right militants, in the Unite the Right demonstrations in Charlottesville, Virginia, on August 11 and 12, 2017. The third, Julien Côté Lussier, alias “Passport,” who was once the spokesperson for ID Canada (an effort to legitimize the “ethno-nationalist” movement among the public at large) recently garnered attention as a candidate in the 2019 federal election in southwest Montréal. Antiracists in his riding revealed that in spite of his militant fascism, Côté Lussier is still employed by the Canadian Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship.

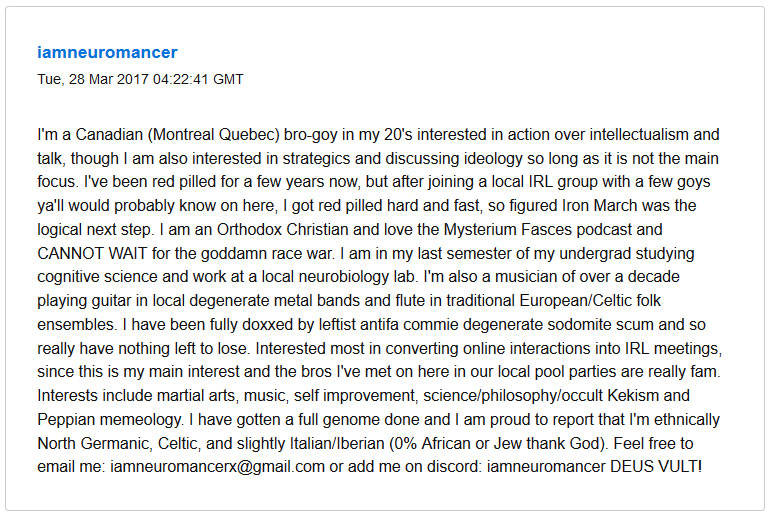

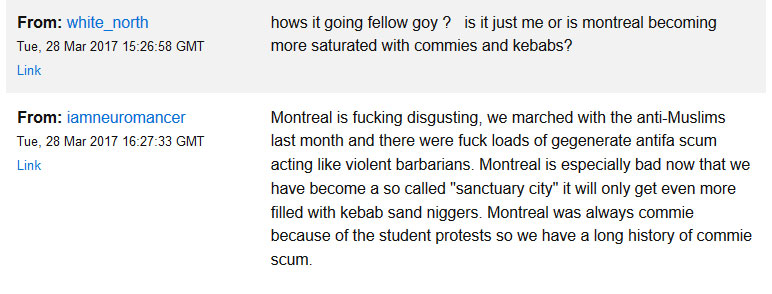

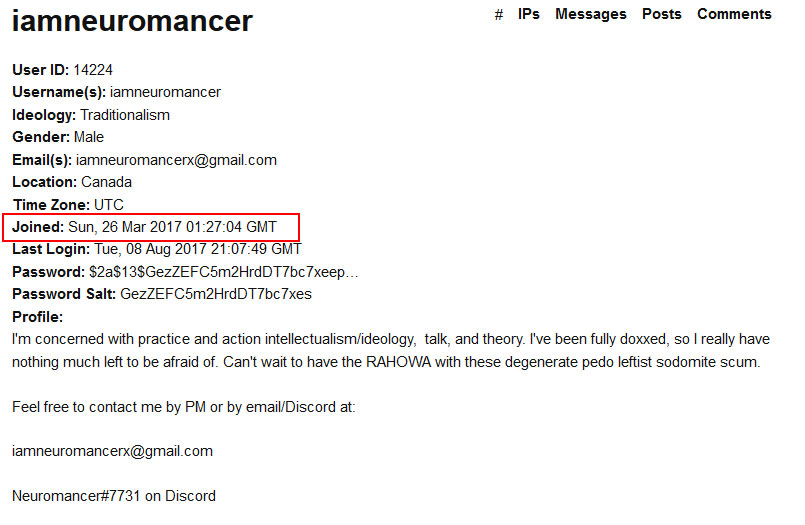

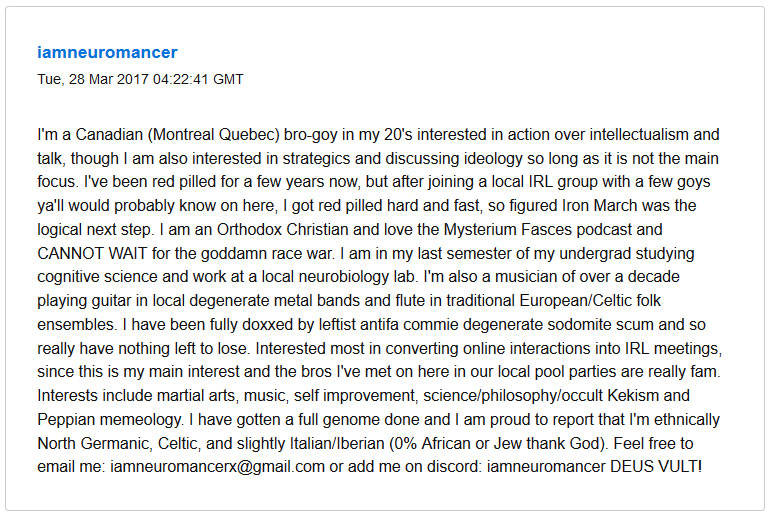

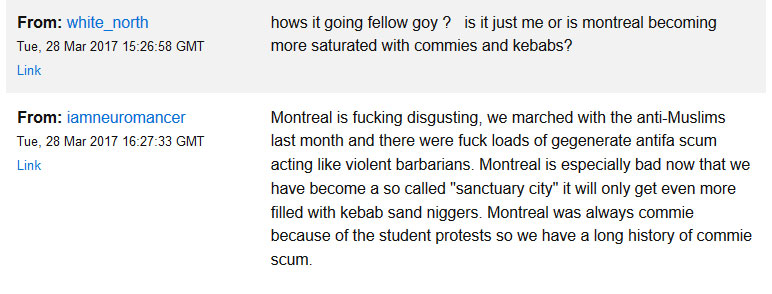

Another extremely active member of the “Montreal Storm,” chatroom is the subject of this article–the user who went by the code name “Neuromancer;” and, as the recent leak of the Iron March forum’s logs proves, also participated in the latter under the pseudonym “iamneuromancer.”

Alexander Liberio, alias “iamnueromancer,” introduces himself to the neo-Nazi forum Iron March.

At this point, Montréal Antifasciste can positively confirm that “Neuromancer” is Alexander Liberio, a Montréal metal musician and a student of Cognitive Science at McGill University up until last year. Possibly feeling the heat after Zeiger was doxxed and the contents of the Montreal Storm forum were published, Liberio made his way down to the U.S. and is pursuing an undergraduate degree in Theology at the Holy Trinity Orthodox seminary in Jordanville, New York. His move is entirely consistent with his vision of Christianity as both synonymous with “white culture” and “inherently fascist”, and in being the best vehicle for achieving the goal of the 14 words (the white nationalist credo formulated by the neo-Nazi terrorist David Lane).[2]

///

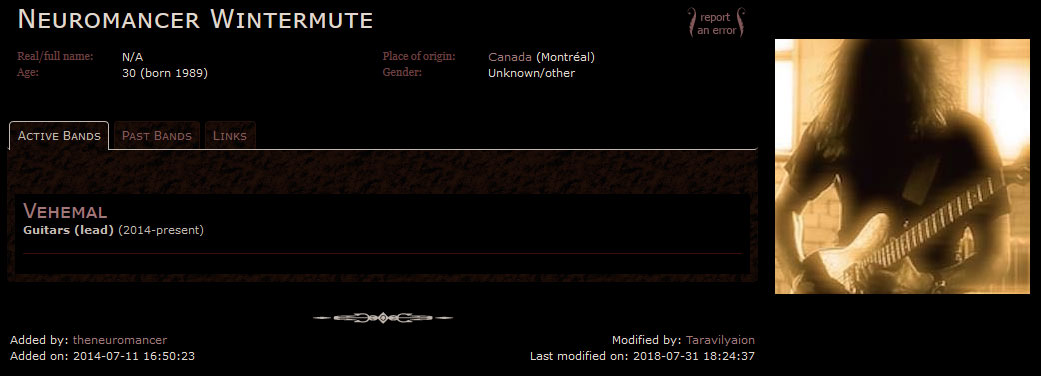

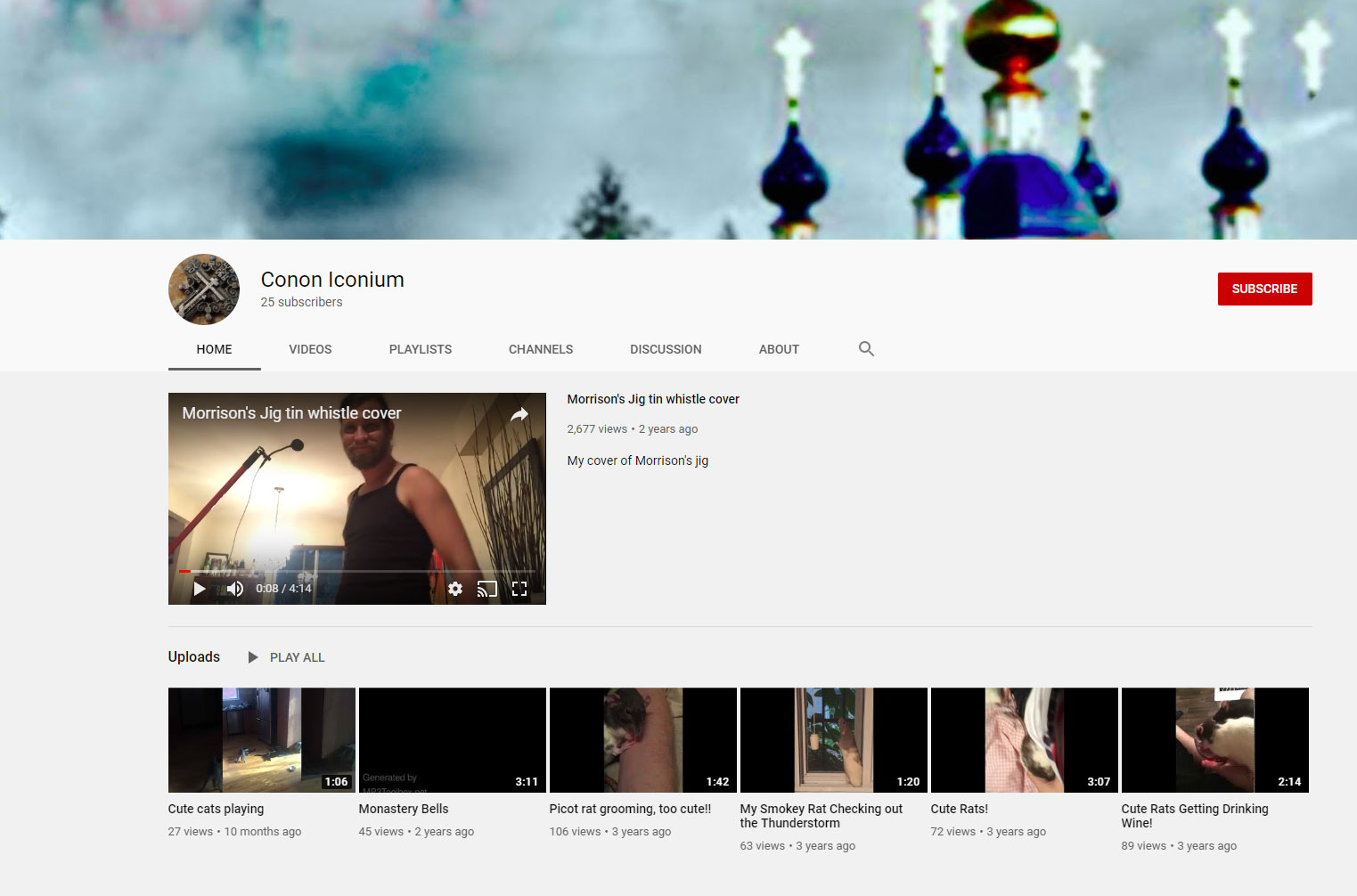

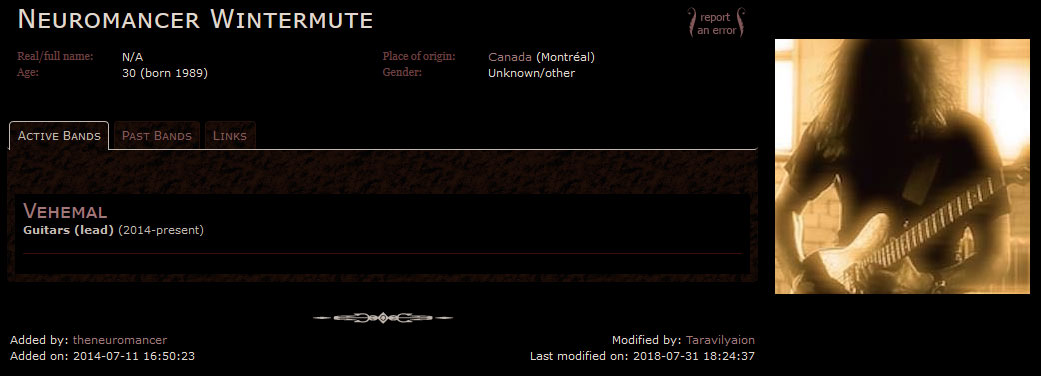

Alex Liberio (b. August 6, 1989), known as “Neuromancer Wintermute” in the Montréal metal scene, has been part of a number of music projects since the early part of the current decade.

Profile of Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromance Wintermute,” on metal-archives.com. NOTE: In February 2022, the band Vehemal got in touch with MAF to request a retraction and issue the following statement : “While it is true that Alex Liberio was our guitarist for a time, we were not aware of his online activities. We want to make it clear that Vehemal condemns all forms of hateful speech and actions.”

It seems that he was the president of the student council at Vanier College in 2012–2013, after which time he focused on his music and entered the Cognitive Science Program at McGill University. It is difficult to say exactly when he turned Nazi, but he complained on a number of occasions about being betrayed by a friend and being “fully doxxed” in 2016,[3] after a white nationalist intervention at a public antiracist event. Oddly, we know nothing about this alleged doxxing and can find no trace of it.

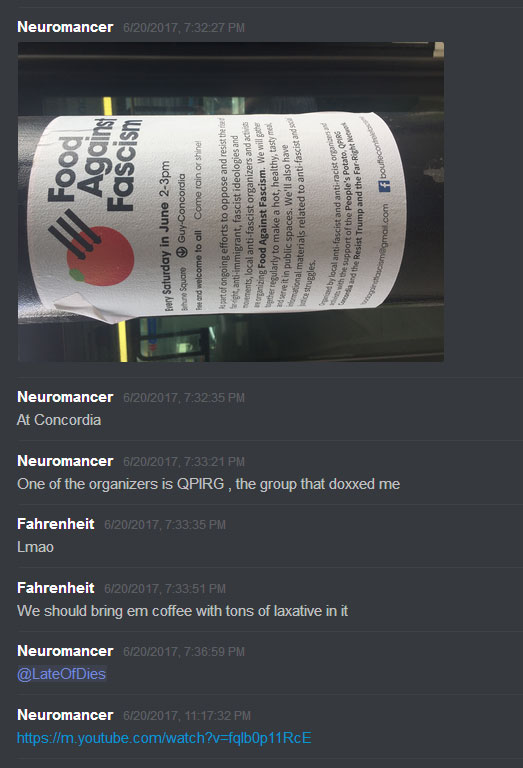

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” claims he was doxxed in 2016.

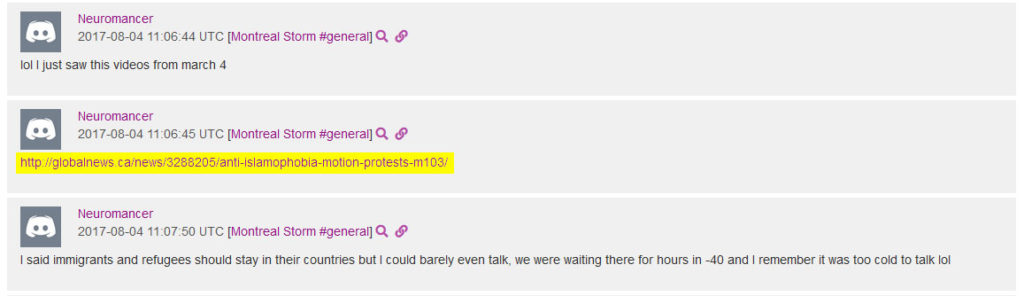

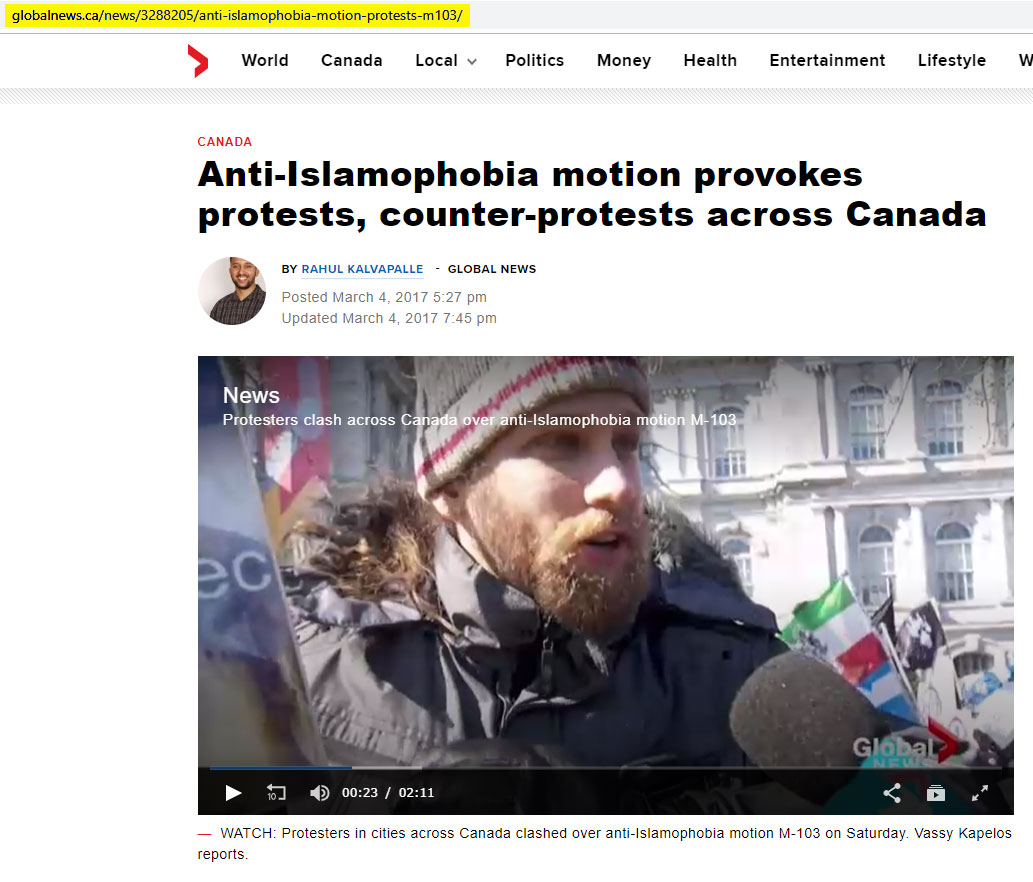

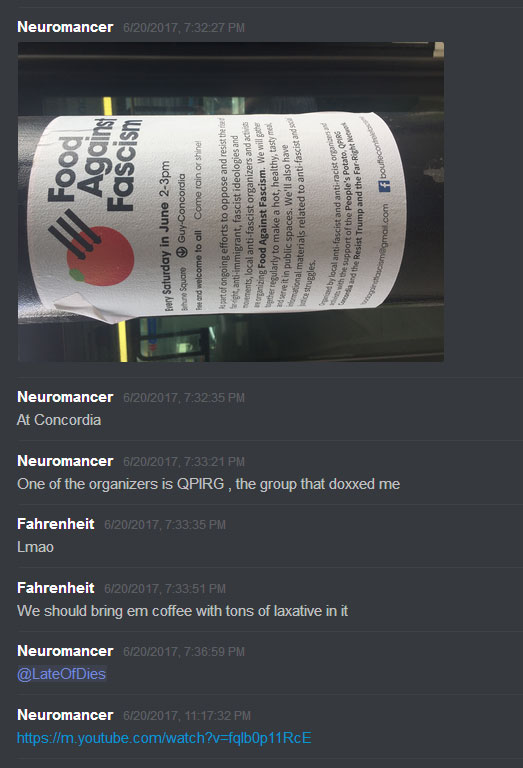

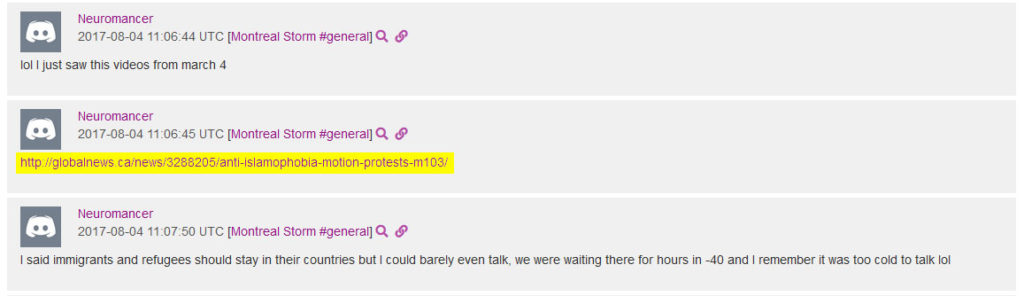

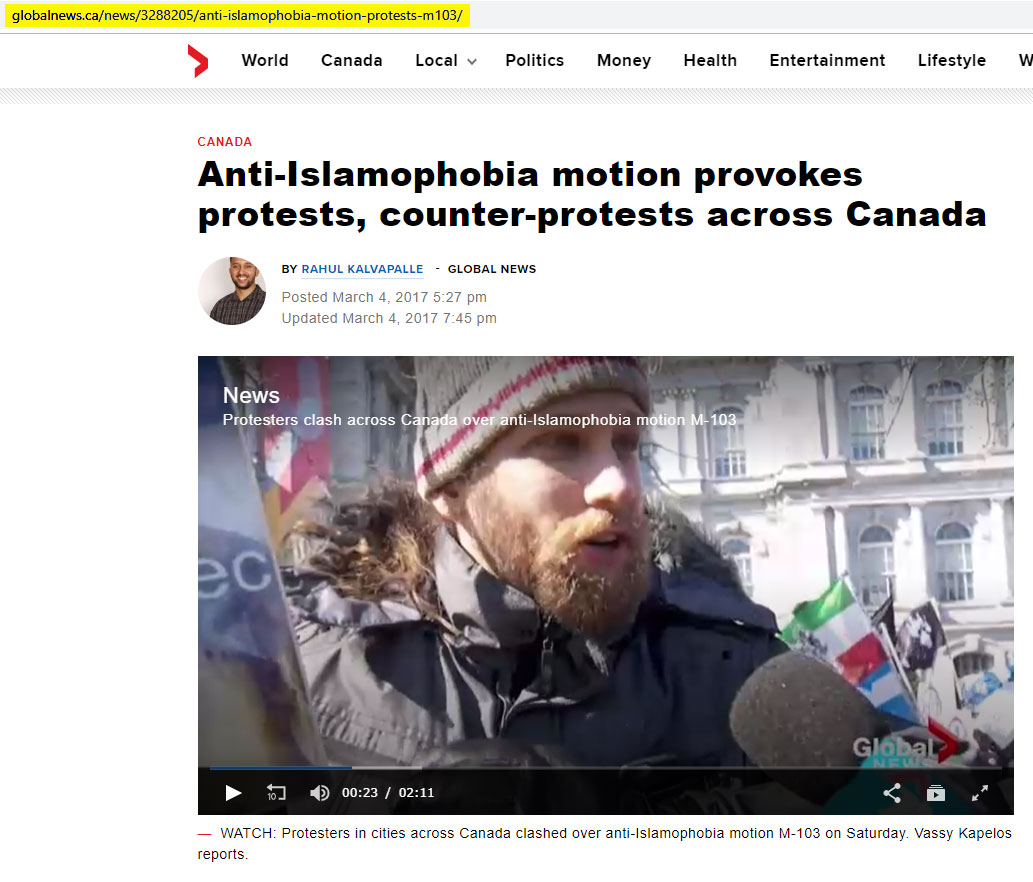

We first noticed Liberio at La Meute’s “coming out” demonstration in Montréal, on March 4, 2017. He was hovering around the PEGIDA Québec contingent in the company of several individuals who were likely the original core of the Montreal Storm group, aka Alt-Right Montreal, among them, Vincent Bélanger Mercure and Athanasse Zafirov. On this occasion Liberio was interviewed by Global TV, which allowed us to put a face to his pseudonym.

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” at the La Meute demonstration in Montréal on March 4, 2017.

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” claims on Discord to have been interviewed by Global News.

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” talks to Global News at the La Meute demonstration in Montréal on March 4, 2017.

On Iron March, Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” talks about participating in the La Meute demonstration in Montréal on March 4, 2017.

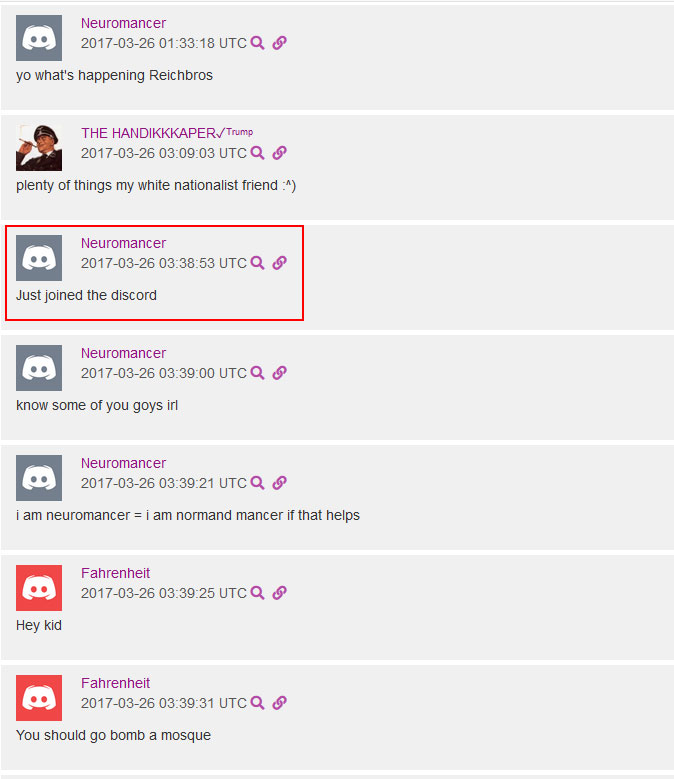

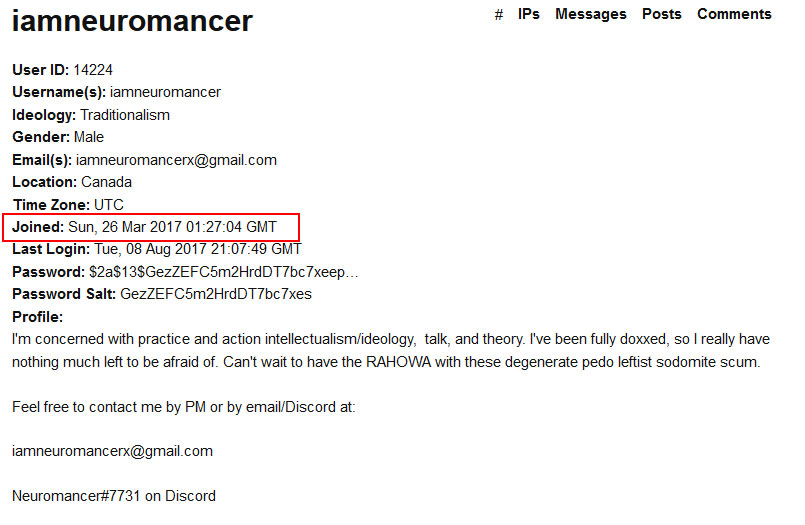

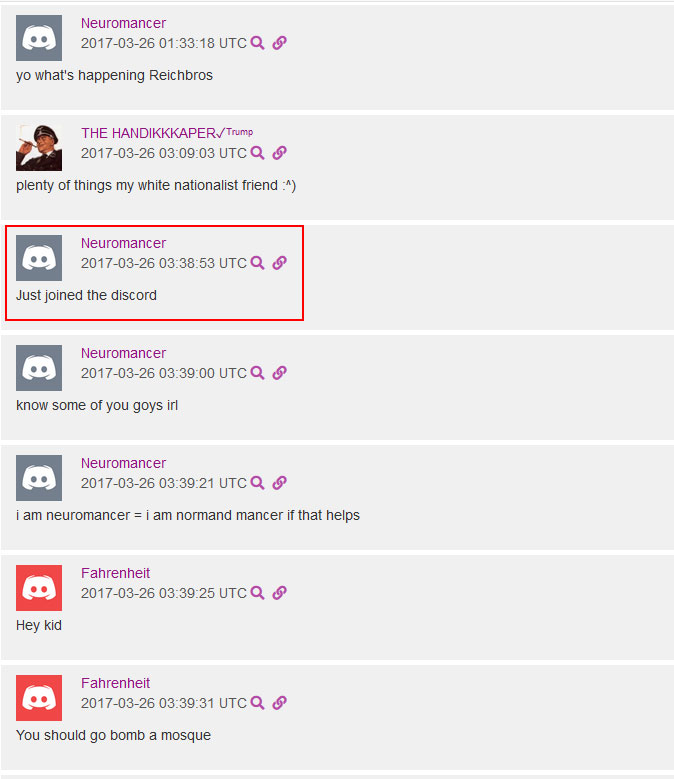

A few weeks later, on March 26, he joined both the Iron March forum and the Montreal Storm chatroom on Discord.

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” joins the neo-Nazi Iron March forum on March 26, 2017.

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” joins the Montreal Storm chatroom on Discord on March 26, 2017.

Uncompromising Nazi

By participating in the Iron March forum, “Neuromancer”/Alex Liberio got to rub shoulders with some of the most influential and dangerous neo-Nazis in the world, including the creator and main administrator of Iron March, Alexander Slavros, and other members of this “accelerationist” community, who went on to create the Atomwaffen Division, an underground neo-Nazi network connected to a series of murders and planned attacks. His proximity to Sohier Chaput and his willingness to engage in “real-life” activities led to his enthusiastic participation in the endeavours of the “Montreal Storm Book Club” (in Daily Stormer parlance, or “Pool Parties” as they were called by users of the alt-right forum The Right Stuff), including the ID Canada project launched by Athanasse Zafirov, Julien Côté Lussier, and others.

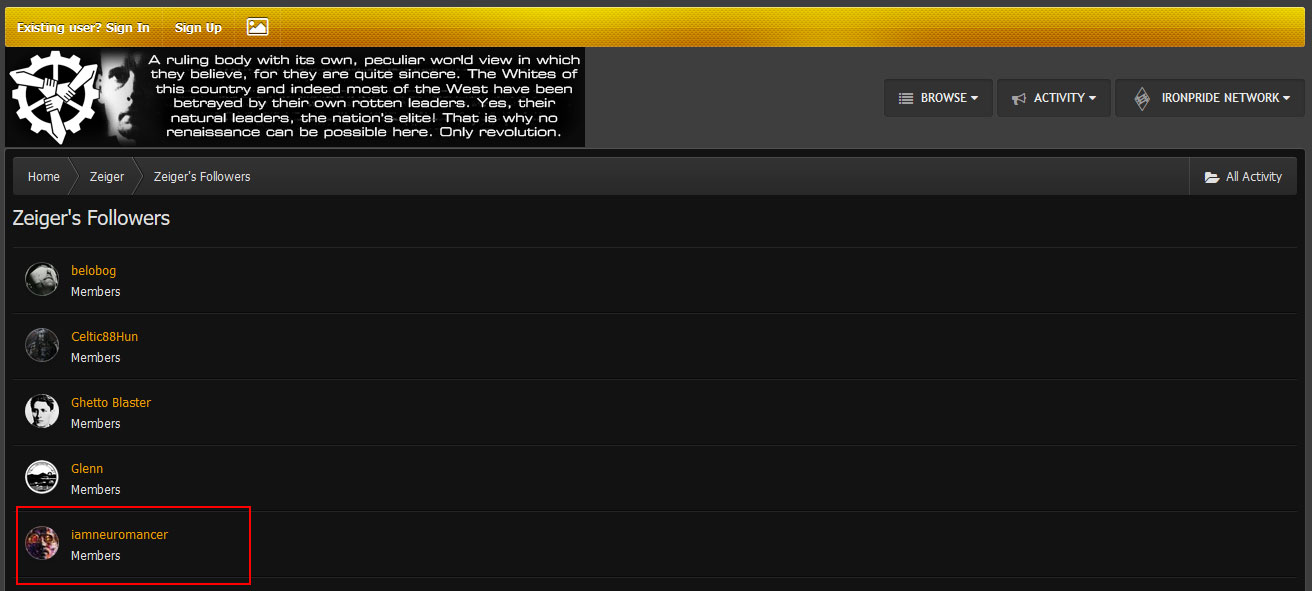

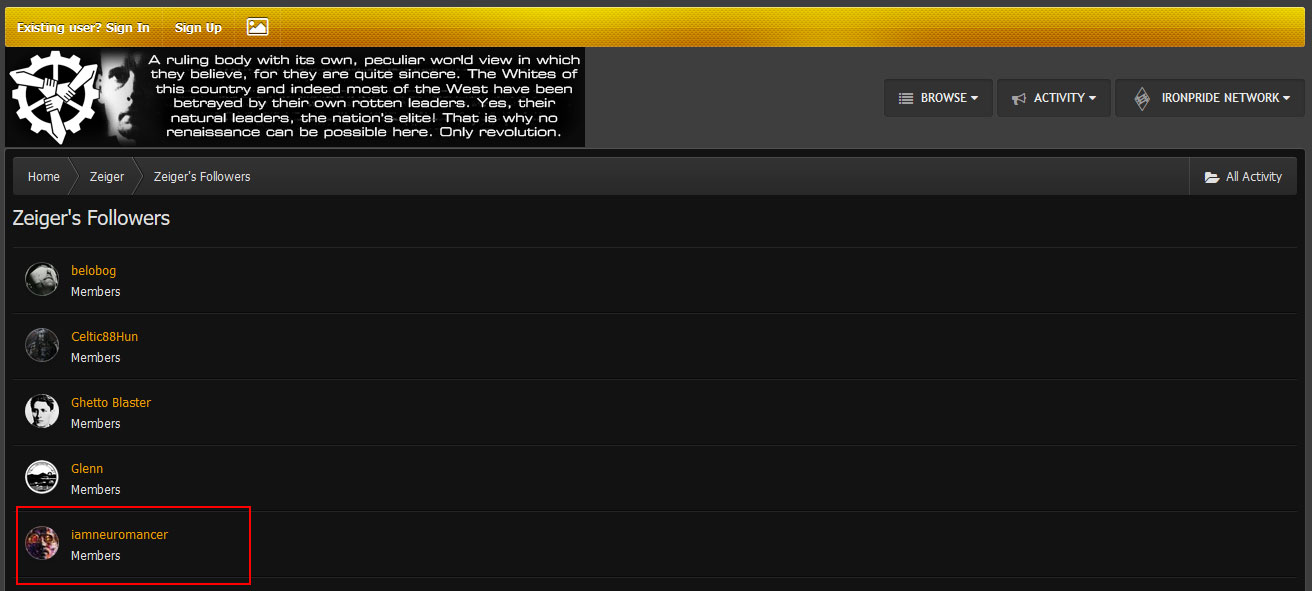

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” follows Gabriel Sohier Chaput, alias “Zeiger” on Iron March.

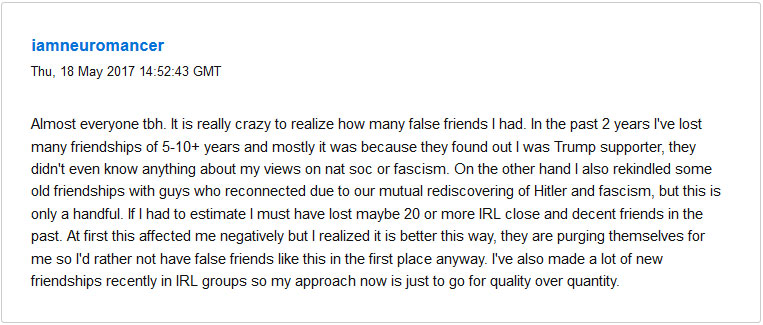

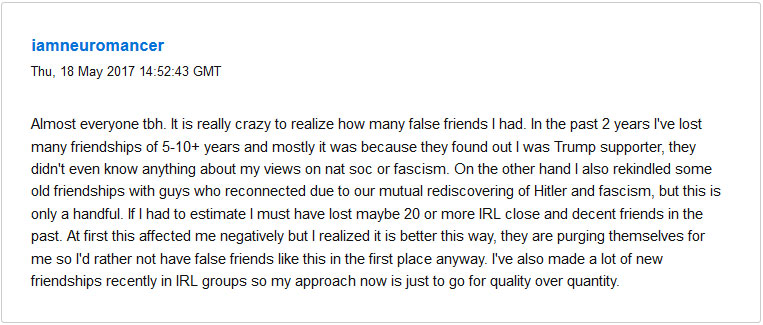

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” says he lost old friends but developed new friendships on the basis of a shared interest in fascism and Adolph Hitler.

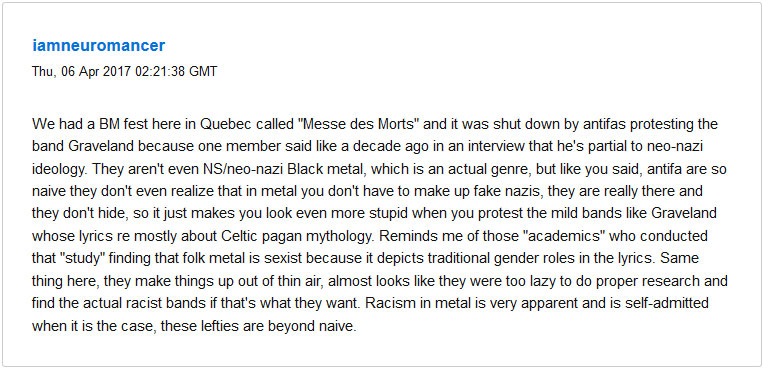

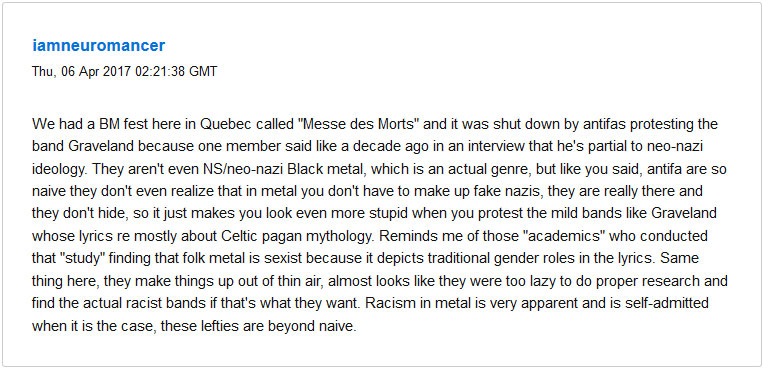

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” complaining that antifascists were out of line when they , because Graveland “isn’t even nazi.” protested a Black Metal festival in 2016, because Graveland “aren’t even NS/neo-nazi Black metal.”

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” makes a direct connection between this Alt-Right crew and ID Canada, an fledgling organization attempting to legitimize white “identitarian” nationalism in the eyes of the Canadian public at large.

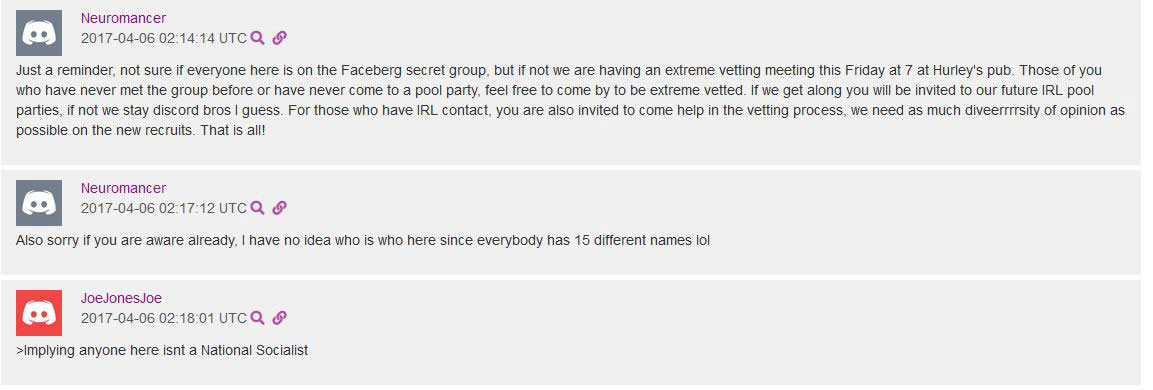

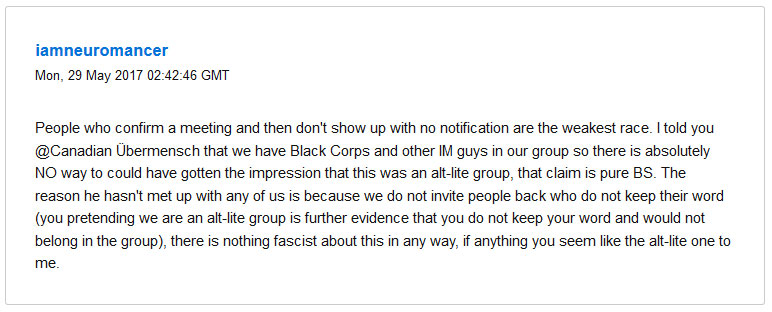

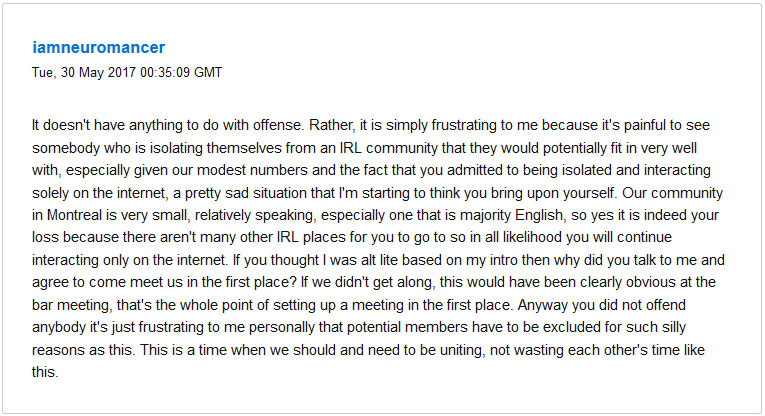

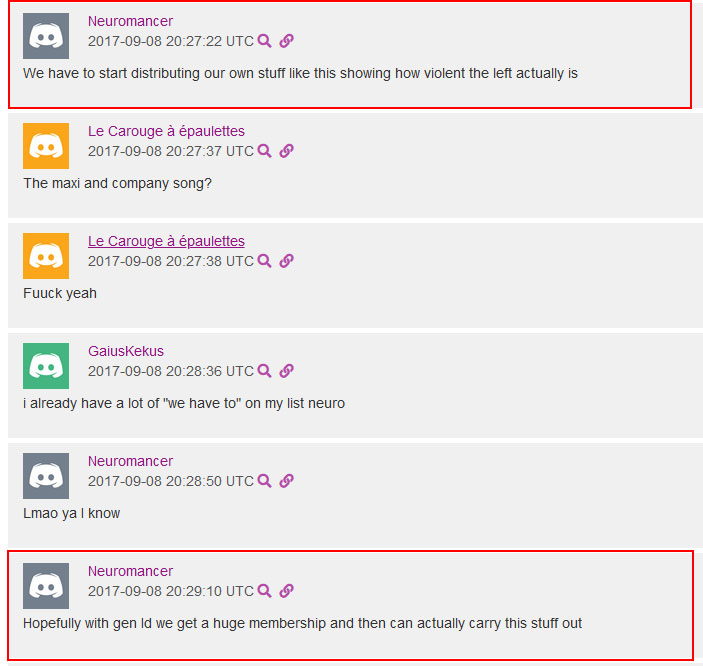

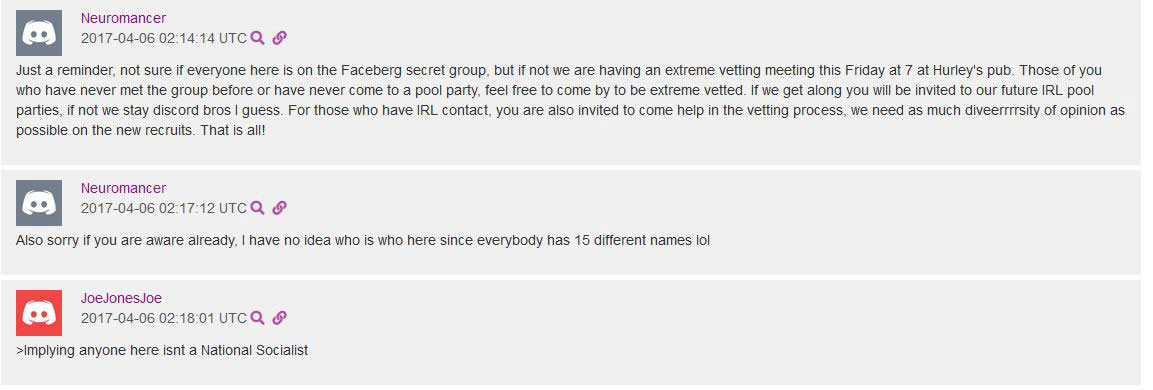

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” mentions the “extreme vetting” measures observed by the group Alt-Right Montreal.

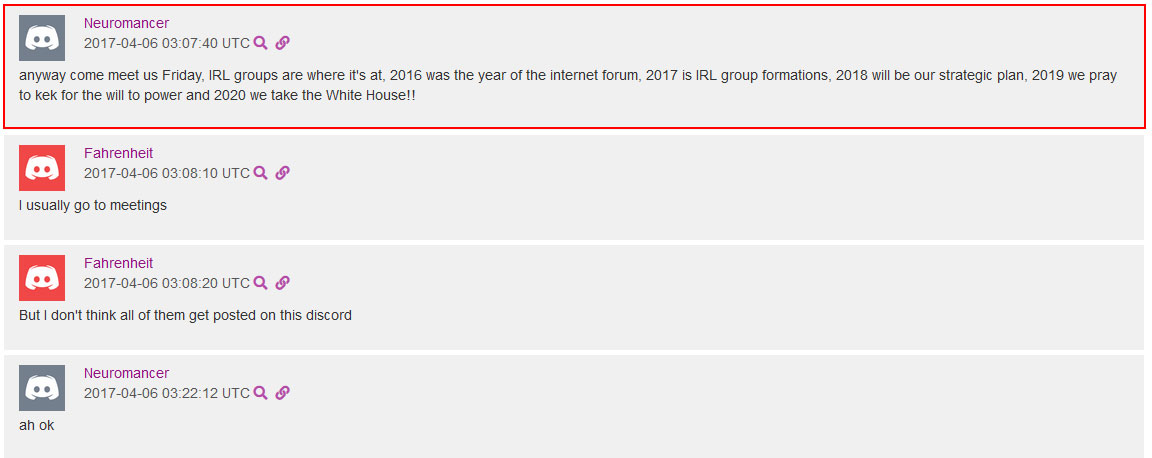

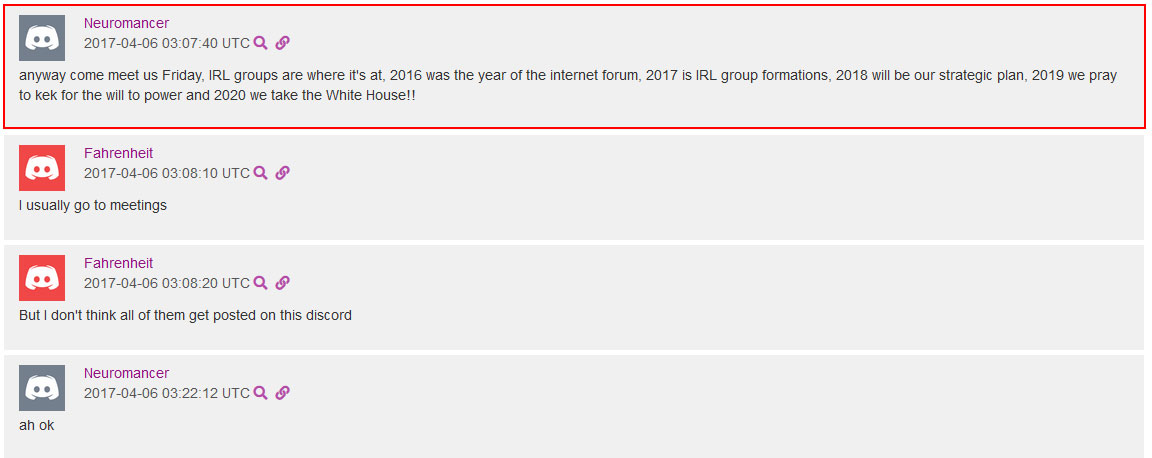

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” argues that 2017 is the year for members of the alt-right to meet in person (and develop a strategy to “take the White House” in 2020!)

![Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” considers Jews “satanic,” “genocidal against [our] people,” and “worthy of hate.”](https://montreal-antifasciste.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/neuromancer_hates_kikes.jpg)

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” considers Jews “satanic,” “genocidal against [our] people,” and “worthy of hate.”

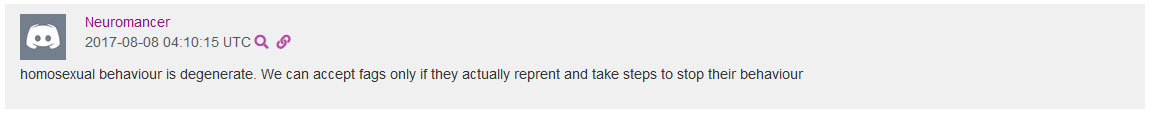

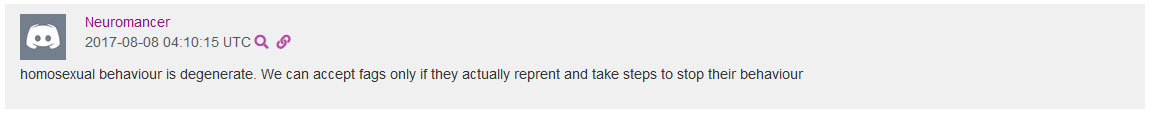

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” to nobody’s particular surprise, is also a homophobe.

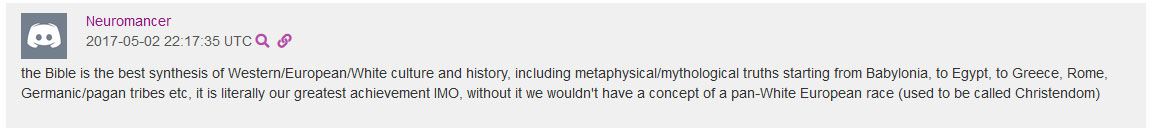

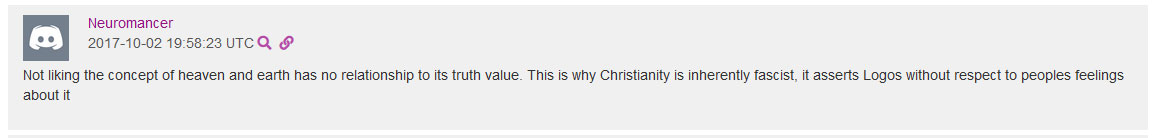

Christianity as a prized tool of fascism

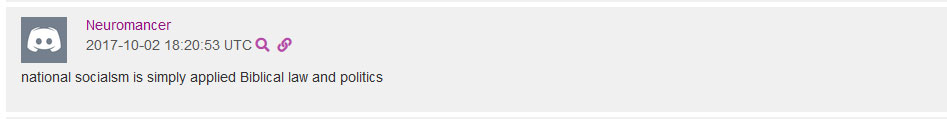

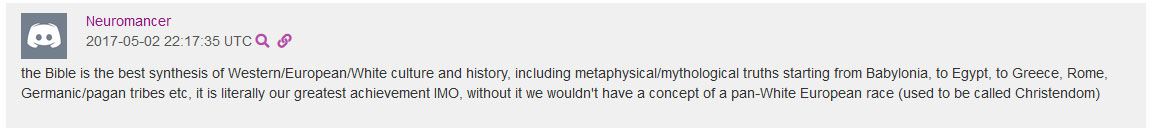

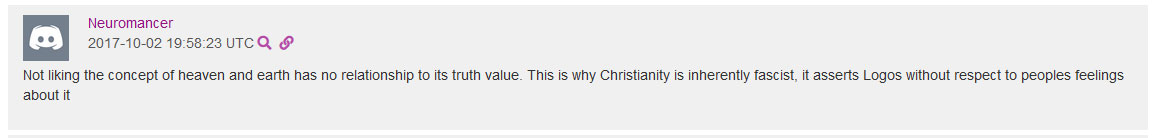

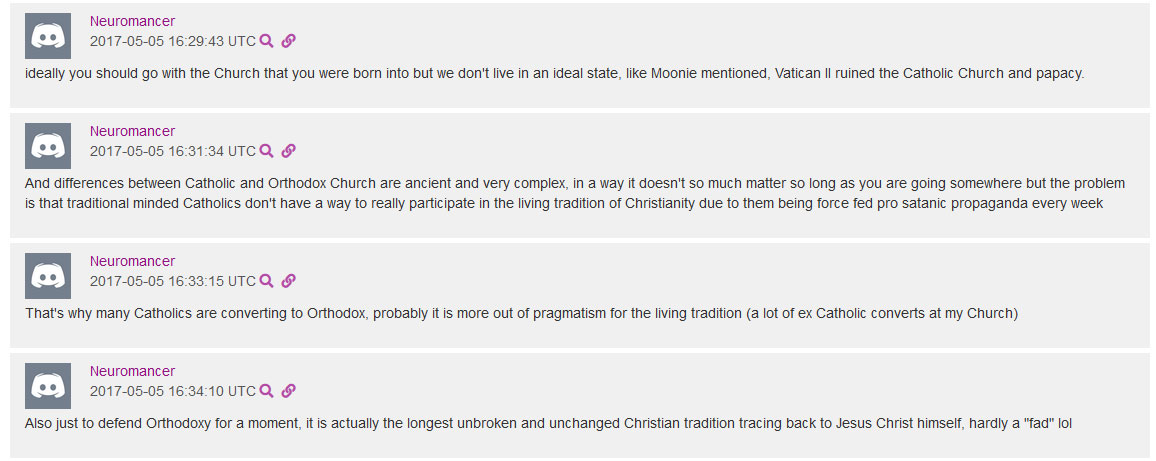

“Neuromancer”/Liberio is part of a not insignificant tendency within the alt-right/neo-Nazi movement that identifies with the Orthodox Christian tradition. He makes no effort to hide his belief that Christianity is the best vehicle for Nazism.

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” believes that Christianity is the best vehicle for realizing the White Nationalist credo of the “14 words.”

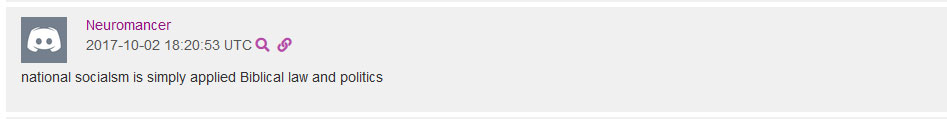

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” believes that Nazi ideology is “applied biblical law.”

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” explains that the Bible is the best synthesis of “Western/European/white culture and history”,(…) without which the concept of a “pan-White European race” wouldn’t exist.

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” explains that Christendom “means whites.”

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” believes that Christianity is “inherently fascist.”

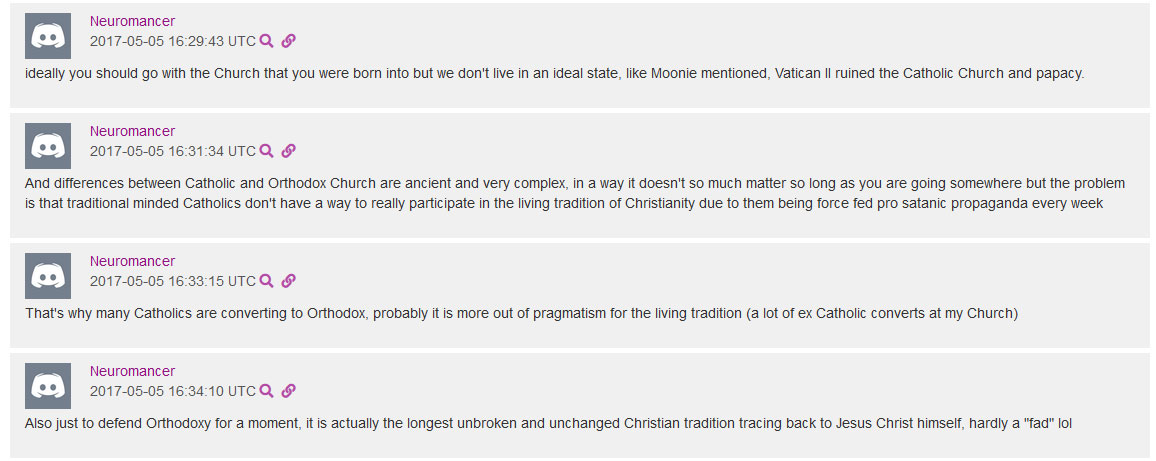

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” trumpets the merits of the Orthodox Church.

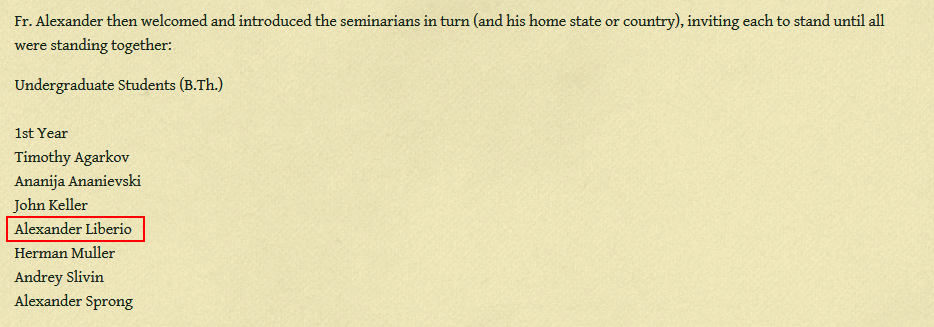

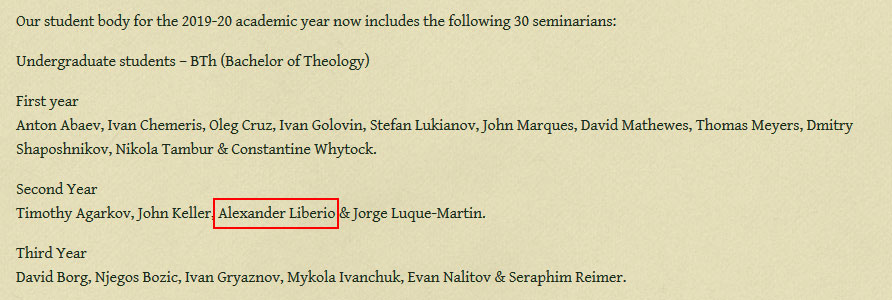

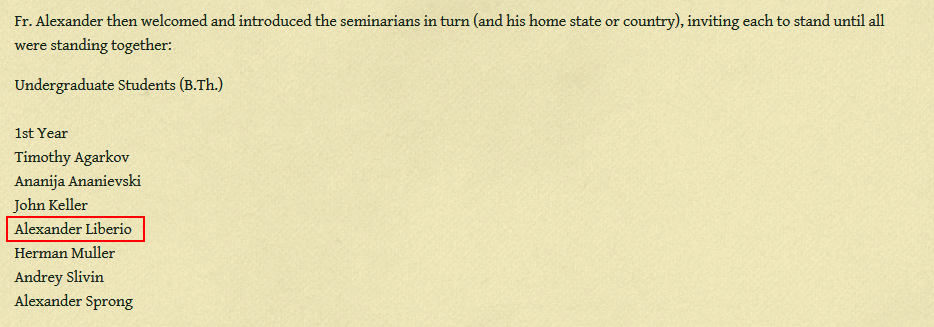

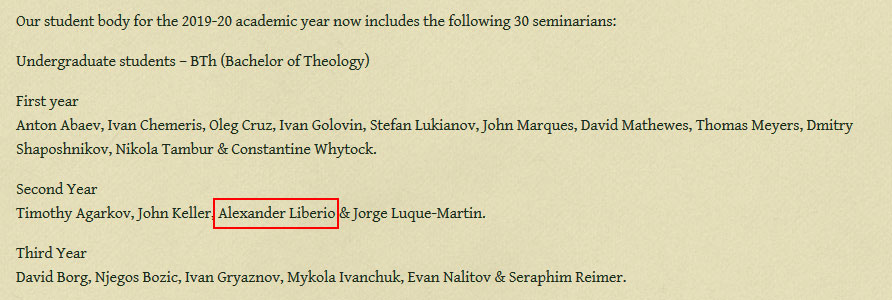

He enrolled in his first year as an undergraduate student in the Fall of 2018, at Holy Trinity Orthodox Seminary, in Jordanville, New York, under the jurisdiction of the Eastern Amercian Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. As far as we know, he is still there today.

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” enrolled in the Holy Trinity seminary of the Russian Orthodox Church in Jordanville, New York, in the autumn of 2018.

Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” still attends the Holy Trinity seminary of the Russian Orthodox Church in Jordanville, New York, in 2019-2020.

The seminary’s disciplinary code stipulates that “The Seminary reserves the right to withhold a degree from a candidate when there is compelling evidence of serious moral misconduct.” It remains to be seen whether or not the seminary considers participating in a variety of neo-Nazi actions and organizations “serious moral misconduct” . . . or if the Russian Orthodox Church actually is an appropriate vehicle for realizing Adolph Hitler’s vision and that of the contemporary adherents of his ideology.

Disclosure of the Evidence

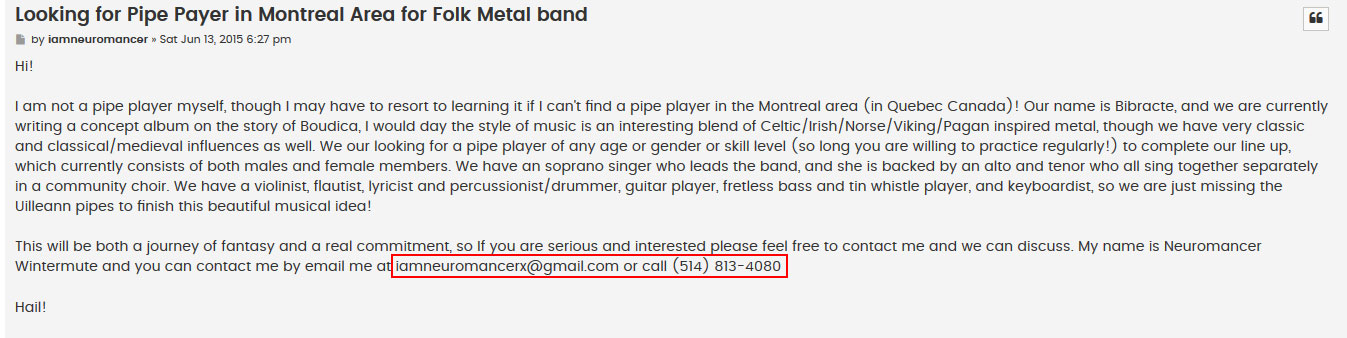

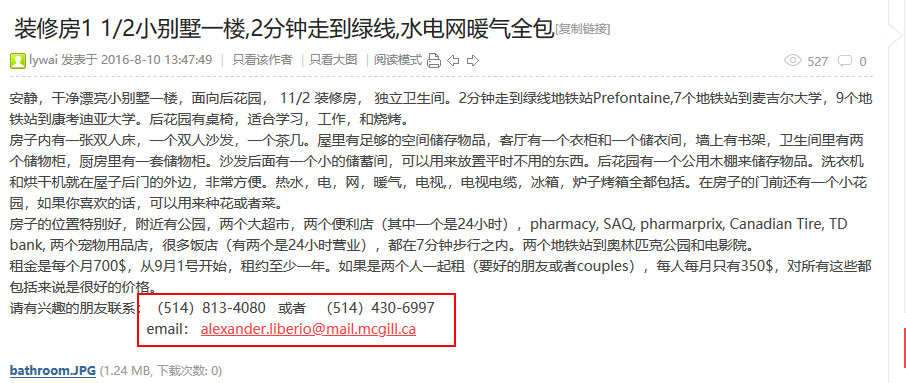

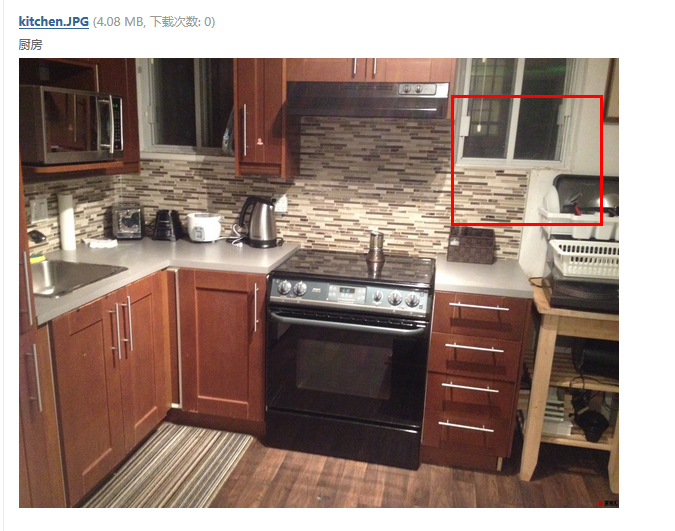

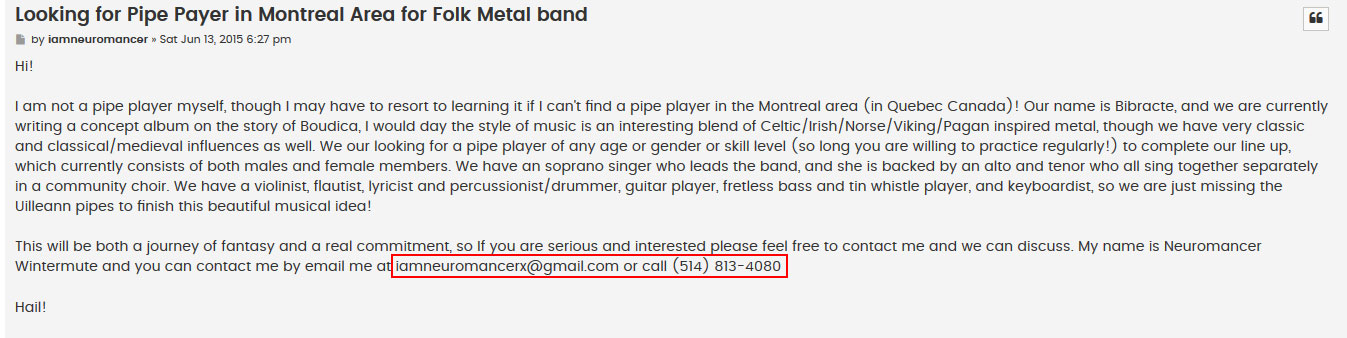

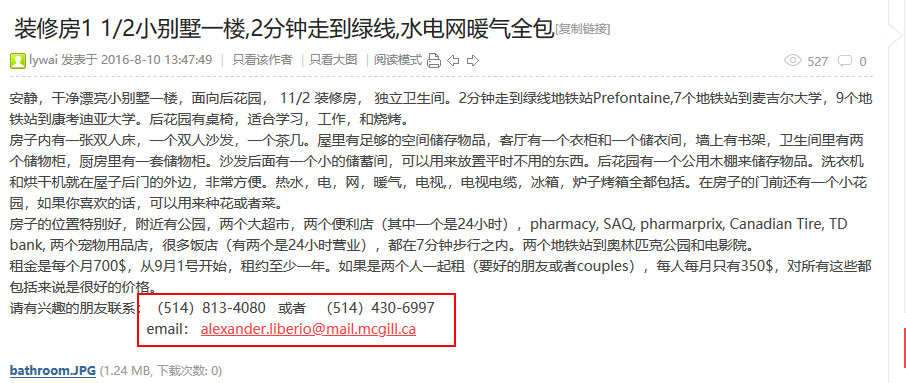

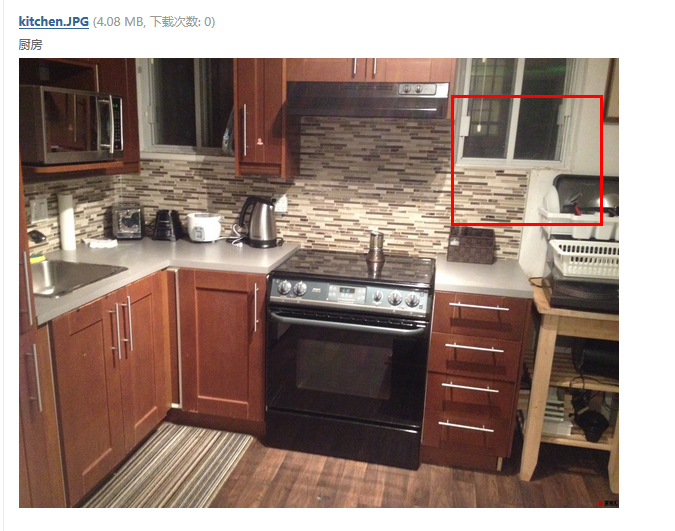

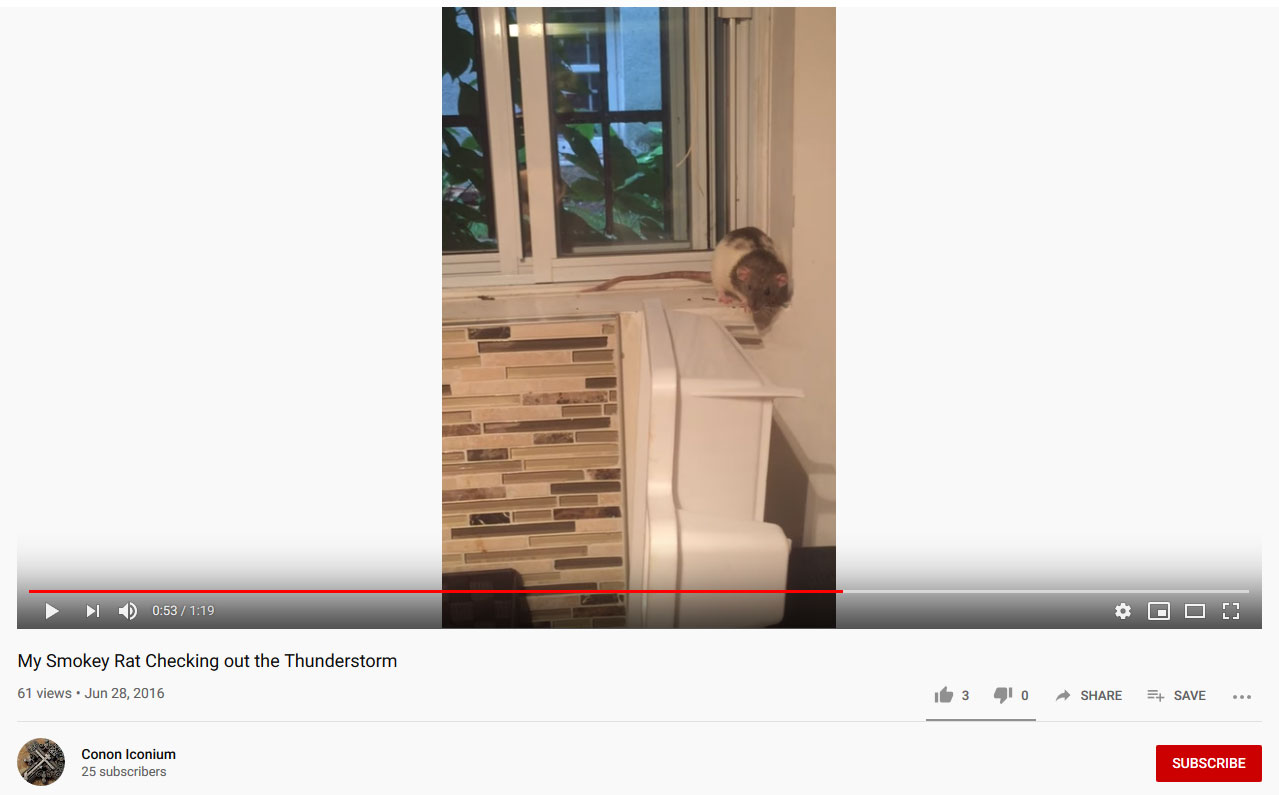

Examining the e-mail address “iamneuromancer” posted the Iron March forum (iamneuromancer@gmail.com), we found a 2015 online announcement to recruit a bagpipe player for a folk metal group (probably Bibracte, which Liberio led for a while with his partner).

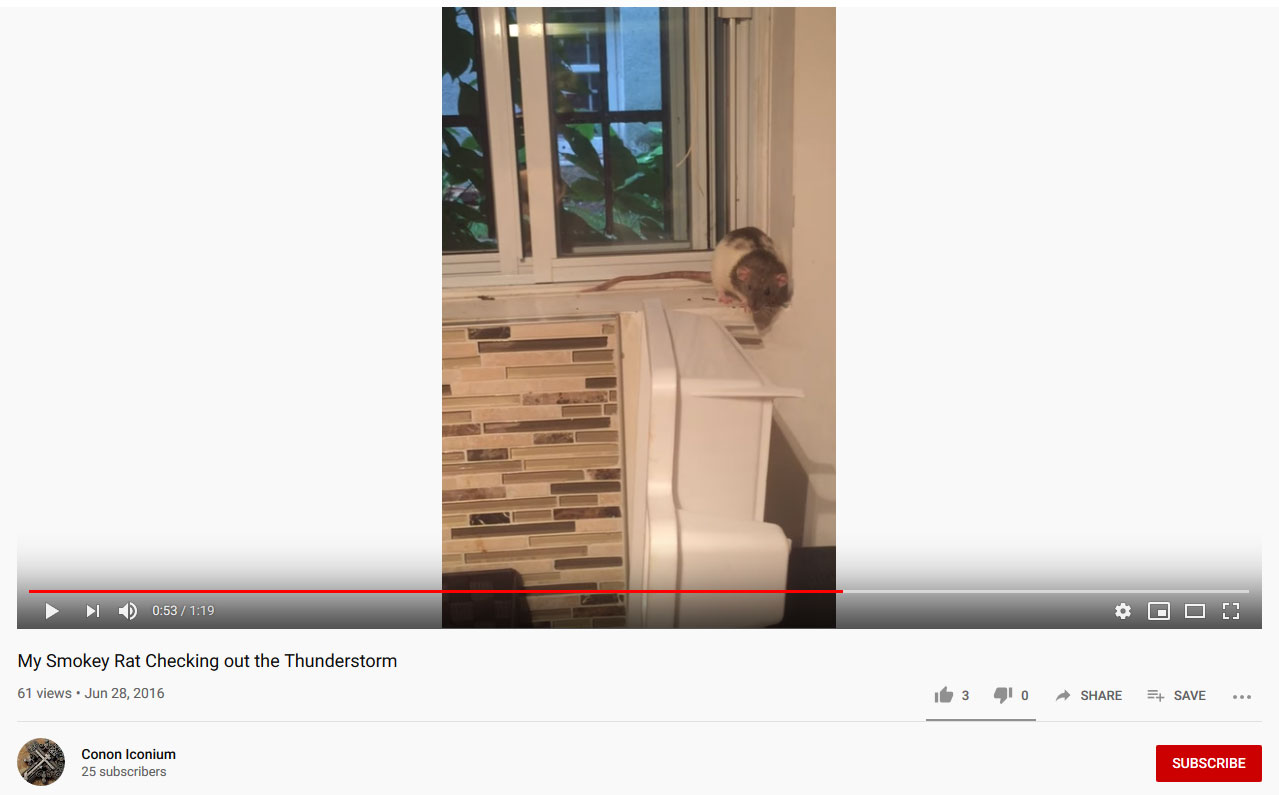

This announcement included a telephone number. Deeper research into the number turned up an announcement on a Chinese forum for an apartment sublet in Hochelaga. Not only do the photos of the apartment published in this announcement show exactly the same décor as seen in a number of videos on the YouTube channel Icon Iconium, in which we see Liberio and his rats, but we also found the e-mail address: alexander.liberio@mail.mcgill.ca.

A search for Alexander Liberio confirms beyond a shadow of a doubt his ties with the Orthodox seminary in Jordanville, New York.

///

What does this mean for these nazis? And what are the implications for our communities?

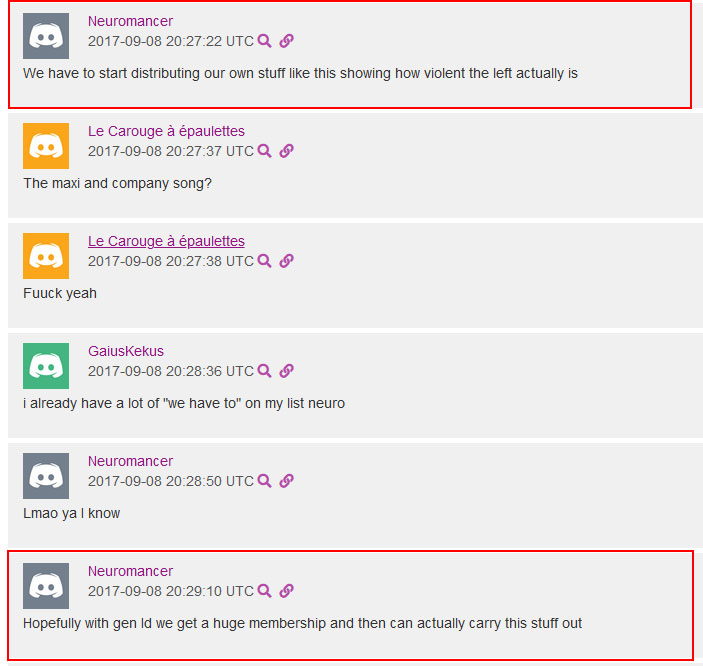

From Charlottesville to El Paso, by way of the Atomwaffen Division attacks and the Christchurch massacre, the online activities of Alexander Liberio’s generation of neo-Nazis have repeatedly crossed over into real life, delivering death and terror in countries across the world. For all that, what stands out about them is how fragmented and fragile their connections were and are; it takes relatively little to disrupt and scatter the networks in the various online chatrooms. But with what consequences? New Iron March revelations have come out every day since the original leak, allowing us to see just how easy it is for “regular” white men to go about their nondescript middle-class lives as students, civil servants, hipsters, etc., while fantasising about race war and genocide, “white sharia,” and “boots on the ground.” The question that we once again face is: What can we concretely expect from these wannabe race war space marines?

In particular, we invite our readers to consider the implications for our communities if the Nazis are left to pursue their activities with impunity.

We intend to redouble our efforts to make sure that these guys can’t simply get on with their lives and continue fomenting hatred as if it’s business as usual. Above all, we will work not only to disrupt their networks but to prevent their reconsitution. The steady stream of attacks and mass murders make it clear that even if these networks are strategically precarious, the tactics they push can lead to disaster.

That said, an effective counterattack necessarily requires a far more vigorous response from antiracist and antifascist communities, a response whereby our ways and means of action reflect our desire to eradicate the Nazis once and for all and secure a viable future for all children.

///

[1] Discord is a software developed to facilitate vocal communication between on-line gamers. Its features, including the private nature of communication, drew the attention of numerous members of the alt-right movement, who began heavily using it between 2016 andt 2018.

[2] David Lane’s infamous credo is: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.” He coined this phrase while in prison for his activities with The Order, a terrorist neo-Nazi organization active in the 1980s and responsible for a number of murders and armed attacks, including the assassination of outspoken Jewish radio host Alan Berg.

[3] Doxxing is a tactic that consists of publicly releasing an individual’s personal information to do them harm in one way or another.

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

![Alexander Liberio, alias “Neuromancer,” considers Jews “satanic,” “genocidal against [our] people,” and “worthy of hate.”](https://montreal-antifasciste.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/neuromancer_hates_kikes.jpg)