From COBP

Print, post, share widely, please

Participate

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

(Link to video of orthodox Jewish gathering being broken up in Montreal – https://twitter.com/i/status/1352813893039648768)

At this very moment, on Wednesday Feb 17, 2021, a pastor is in jail for holding worship services. This is a milestone in Canada’s slide into authoritarianism. Canada is now jailing dissidents. Christians are now a persecuted religious minority. So are Jews. Multiple gatherings of orthodox Jews have been broken up by police in Montreal over the last month. Not only is a clear example of oppression against a historically oppressed group, it is always telling about the times that we are living in. I don’t think that most people realize what this means. It means that we don’t have rights anymore.

Religious freedom is very clearly featured in the Charter of Rights and Freedom, which is supposedly the highest law in the land. Yet, at this very moment, a Christian pastor is sitting in jail because he continued to hold worship services when the state ordered him to stop. If this doesn’t concern you, it should. If Christians don’t have the right to assemble, it means neither do you. It means you don’t have a right to go to pow wows, or punk shows, or wherever it is that you find your community. If you are not free to do what you want to do if you had the choice, it means that you are not free. And, clearly, Canada is not a free country.

The state has now made it clear that it means business. Civil disobedience, even when very clearly protected by constitutional rights, will not be tolerated. What happens next depends on how people react to this. Will people realize that our rights are being trampled upon and stand up against this injustice, or are have people been too lulled into complacency to care?

If you have a heart in your chest that beats, and lungs that breathe and blood that pulses through you, you should realize now that you’ve got do something to stand up to this insanity. The existence of a virus does not justify prohibiting basic human activities like coming together to sing, to pray, and to affirm and cultivate community bonds. Whether or not you’re a Christian, whether or not you like Christians, it should consider you deeply when people are being prevented from practicing their religion. Need I even draw the parallels to the persecution of religious minorities in every totalitarian regime?

If you are not sympathetic to Christians for political reasons, please consider the following: this past Summer there was a Sun Dance which the police tried to break up. The Sun Dance Chief refused to back down, and the police left. Then Trudeau specifically said that indigenous ceremonies would be allowed to continue. Of course, indigenous ceremonies were outlawed for much of Canada’s history as part of a deliberate campaign of cultural genocide. That is a line that should not be crossed. To do so would to make absolutely clear that the Canadian colonial project is still genocidal. If the state is jailing Christians, historically privileged in Canada, from gathering, are we to trust they won’t also jail indigenous ceremonial leaders for refusing to cancel ceremonies?

If this is happening to Christians, it can happen to other religious groups as well. Would the injustice be more obvious if it was happening to people of colour instead of white people? Well, it may not be long before it that occurs, because there are certainly devoutly religious people of colour who feel very strongly that they have the right to worship, and will continue to hold services.

We as anarchists must stand against the forceful imposition of a police state upon us. True, anarchists have often been at odds with Christians, but there is also a strong tradition of Christian anarchists, such as Leo Tolstoy, Jacques Ellul, Dorothy Day and Ammon Hennessy.

I think that we would also do well to remember the words of Amon Hennessey said: You’re born free. Then you wait for someone to take that freedom away from you. The degree to which you resist are the degree to which you are free.

It is time for us to prove exactly how free we are. We must resist, we must raise our spirits up out of this damned lethargy and express our solidarity with our fellow people. Just think; what if the shoe were on the other foot, and it was anarchists who were being jailed for their organizing activities?

One thing that the system seems to have done really well is divide people into Left and Right, terms that no longer possess the descriptive power they once did. If most liberals are now for universal restriction of movement, then the term liberal has come to mean the exact opposite of its original meaning, and the word is useless. The new political divide is really between people who are pro-totalitarianism, and people that are contra. If this is the divide, then anarchists are on the same side as the Christians and Jews who are asserting their right to gather. If we are looking to build a revolutionary movement across cultural lines, it will involve respect for the spiritual beliefs and practices of other peoples. If we want a powerful movement to emerge, we must practice solidarity with other people.

So far, most Leftists have remained silent on the matter of religious freedom. Across the country, churches have been fighting for their rights to hold worship services. Yet anarchists have remained silent on this issue. Are people not able to see this injustice?

It is important that the Left see this as what it is. It is a fundamental human right violation to jail people just for practicing their religion. I worry that many Leftists have ceased to believe in the universal principles that classical liberalism is based upon, but to those true liberals, you cannot stay true to your beliefs and tolerate this. This is persecution. Please understand that Christians deserve the same freedom to practice their cultural practices that Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists, and everyone else does. The pandemic is no excuse for this, and we must make a stand for what we believe in, if we are to say that we believe in basic human rights. And may we never have to lament a variation on the following:

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out

—

Because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out

—

Because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out

—

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

(This piece is from April 22. I submit it because I think that it is some of the compelling anarchist writing that I have found that captures the feeling of the great confusion of 2020. I think that this piece has tremendous literary value and I would love to see it translated into French.)

This flyer was distributed in different neighborhoods of Athens. Published April 22 on actforfree.nostate.org

It all happened without anyone really realizing it. And now we find ourselves locked up in our houses, waiting for next day’s news which we all know will contain more and more restrictions. Society is in crisis, they say, because of a virus spreading. The government is pressing that it is of most importance that we all do exactly what it says, and that by this we take our responsibility and act in solidarity. It stresses that the state of emergency is of course temporary, but necessary to win the war against what is seriously threatening our well being.But wait a minute…

Which virus? Actually, we cannot know. All the information, numbers and statistics that are at the base of the imposed confinement are in the hands of the government and the specialists that work for them. It is not a matter of denying the actual existence of a virus going around, but to realize that the knowledge of its characteristics, how it spreads, how it can be tackled, but also the data concerning its impact, is in the hands of scientists around the globe, which often don’t agree even among themselves about how to interpret them or which practical conclusions they would entail. The conclusion of the authorities on the other hand is simple; they know, we don’t. And because of this we owe them complete obedience. The mass media is playing its classic role of servant of the system magnificently. Deciding what exists by only showing and endlessly repeating the story by the authorities, not giving a millimeter of space to deviant voices of any kind. Their job consists of fully preparing the grounds for the next even more totalitarian decisions.And isn’t a virus the perfect enemy? Invisible and possibly everywhere, with everyone not complying to whatever rule is invented becoming an accomplice of that enemy. Justified to be oppressed with fines and prison sentences. A perfect context is created in which the state can shine as the ultimate savior.

Which responsibility?

And so we cannot open a newspaper or put on television without being told we should ‘take our responsibility’. But what does this mean then?They are asking us to blindly follow the orders of some politicians. But aren’t they the same bureaucrats we were distrusting before? Didn’t they prove so many times to be greedy and corrupt because they are driven much more by personal interest than by care for others? Didn’t it show again and again that their hunger for power is bigger than any sense of justice or reason? And now again, maybe the thousands of euros making sure helicopters are in the air controlling if we are staying in our houses could better be used in mmm… health care for example? These are the kind of people that are asking us to trust them, no questions asked, and call it ‘taking our responsibility’. Would we not be doing the opposite then? What we are really asked to do is to give up any conscience, critical thought, and autonomy, to welcome extreme government control in every aspect of our lives.

Our dIgnIty In quarantIne?

The misleading spectacle continues. We should obey the extreme measures being taken out of a sense of ‘solidarity’. Isn’t it cynical to hear these words from the mouths of the representatives of a system that is based on the exact opposite of solidarity? The whole year through we should run around like chicken without heads to keep up with the constant game of competition, to be exploited, to be hunted by cops for whatever reason they feel like that day, and be robbed by statesmen which made their profession out of it, and now they come to us and dare to speak about solidarity?

They dare to act as if they care about our well-being? What about the millions of people living in poverty so people like those in the government can be rich? What about all the people dying at their crappy jobs feeding the relentless economical machine? What about those being tortured in the police stations by the uniformed executioners of the state? What about the thousands of migrants dying at the borders every year? Where is the government with its big speeches about solidarity then?

While they are trying to feed us their hypocrite tales about solidarity in reality we see that the lockdown is locking loads of people up in unbearable circumstances. Children in their homes under the uninterrupted rule of violent parents for example. Or partners, husbands and wives stuck in abusive relationships. Thousands of migrants being trapped in camps, in even worse conditions than usual. In prisons all visits stopped, as did all access of prisoners to material, food and clothes coming from the outside. Empty spaces in prisons are being used to isolate prisoners with symptoms of the corona-virus, these spaces being empty in most cases because they are in not fit to host prisoners.

One can only imagine the effect this will have on the health of the prisoners being dumped there… In the prisons in Italy massive revolts broke out after general restrictions on all levels were introduced. Probably the only way for the prisoners to save their dignity seeing the conditions they are forced in. Also in Spain and France prisoners are standing up and fighting back, as other prisoners around the world.The state doesn’t know what solidarity means and has never been concerned about our well-being. As always, it will be up to us to take care of each other, and make sure that those that need it get support. When the government uses the word solidarity, it is only to give a feeling of guilt to those who don’t obey their orders, and to push people to internalize its authority.

Which crisis?

So they tell us we are in crisis. Maybe somebody can tell us when the moment comes that we are not in crisis? From the financial crisis to the climate crisis, through the migrant crisis to the corona crisis. It seems the system has a lot of different names for what always turn out to be periods which are used to restructure its power, to enlarge and intensify its oppression. In this case, especially in this case, it will not be different. The idea of a condition of crisis has always been used to contextualize a further totalitarian evolution of power. The rhythm on which this evolution is forced is not always the same of course. The bigger and more urgent they can make the crisis look like, the bigger and faster the change can be. It goes without saying that the current ‘crisis’ is giving the government (all the governments) the perfect context in which to take giant steps in the development of their mechanisms of control and oppression.

Which exceptional state of emergency?

It is always repeated that whatever steps that are taken are ‘temporary’, but this is a lie. Many occasions in the past showed us that at least a part of the measures from ‘states of emergency’ were kept afterward and were embedded in laws never to be taken back. From big examples like 9/11 that changed forever the abilities of states to track, trace and record everyone, to more recent times in which terrorist attacks were used as a pretext to introduce many new ways to bring to court whoever disagrees with the state, to get the army (in a lot of places permanently) on the streets, to boost the general collection of data etc. And here, didn’t the new government launch a general state of emergency in the capital aimed at the total repression of the unwanted (homeless, anarchists, drug users, squatters etc.) since last year? We all know they are working non-stop on creating an image of ‘crisis’ (in this case some kind of ‘security crisis’) to justify its absolute thirst for power, implying that its fascist behavior and totalitarian policies would be of ‘necessary but temporary’ nature… And now, what is massively happening? People turn toward the internet for their needs, for all their needs.From communicating to consuming, from working to relaxing. In the blink of an eye a big part of life has deliberately been transferred to cyberspace. By this it becomes even more easy for the state to follow, register and surveil the daily activity of whoever. But especially, it is our own will and creativity to ‘solve’ a lot of the problems being caused by our mass imprisonment, that help normalizing it and finally push its acceptance. The managing of the current situation will bring forth an unimaginable set of experiences, tools and know-how that can and will continue to be used whenever estimated necessary by those in power.

Which war?

But all objections or criticisms are undesirable or even dangerous, because after all ‘we are at war’. At war against a biological event, against nature actually. Isn’t this indicative for these modern times? We forget more and more how to live with or in nature, but multiply and intensify our wars against it. Our whole way of living is built on the exploitation of nature and, if this reality is not overthrown soon, its total destruction. Maybe it is the western arrogance culturally believing we are above all things, and so always extending our ways to control them. Always looking at nature in terms of its practical value to ‘civilized’ society. And when we are confronted with something that causes discomfort everything will be put in place to tame it, to manipulate or eradicate it. So a constant war is being waged, against nature, against life and against death. It became an unimaginable thought that we would not own nature but be a part of it, and by this can be subjected to some of its conditions…Of course nobody wants to die, or see its loved ones die or suffer. We want to live! But is merely surviving at a certain point the same as living? Is it possible to live in a cage, or can we at best survive in one? Are we ready to take away all risk of living to have a better chance of survival? One could say these are philosophical questions, good to pass the time but nothing to do with real life. Well, at this very moment all life is being taken away from us because we are told that this is the only way to survive. Every day in isolation is an attack on our autonomy, on our ability to think and act for ourselves, to live, love and fight.

The quarantine has to be refused, because our dignity cannot survive in it!

The lockdown has to be broken, because our desire for freedom will not!

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

After the eviction of the anarcha-queer-feminist house project Liebig34 on 9th of october 2020, the offensive of state and capital against self-organized structures in the northern area of Friedrichshain and other parts of the city did not cease. The Liebig34 is since then under the control of the owner and the presence of his gang had also an affect on the local life. The so called Dorfplatz (“village square”) lying directly in front of the house was during the last months less used by residents and visitors as a common space and saw some minor confrontations with the invaders. With having taken one of the strategic points in the area and in the same time removing a political obstacle, state and capital could focus on the Rigaer94, which lies just some meters away from the Dorfplatz and has been a constant topic in the medias over the last year.

A few days ago, cops and diggers destroyed a settlement of homeless people in Rummels Bay, a few kilometers from us. The pretext here was the extreme frost, in reality it is also there to serve the profit of investors. Also expected in the next few weeks is the eviction of the Potse Youth Center – the city is in the process of removing any rebellious site.

What started with ridiculous complaints of the parliamentary opposition about the fire-security in the house became one of the central issues of the forces of order. All those who were spending their energy for years to create a depoliticized image of Rigaer94 as a house full of brutal gangsters began to speak about their worries that the inhabitants could tragically die in a fire. Their rhetoric is very transparent because it was based mainly on the fact, that the house has several mechanisms to quickly barricade the main entrances. These barricades are in fact a central piece of the safety of the inhabitants. Not only the social media is full of fascist threats to target the house but also the cops proved over the last years that they are not only capable to launch very violent legally supported actions but also to openly coordinate with parastate forces, namely organized fascists and the mafiotic structure of the real estate industry. For example the owner of Liebig34, but other companies as well, are well known in Berlin for evicting houses by setting them on fire. The message behind the fake discussion about our safety was nothing but a direct threat and a call for parastate forces to set our building on fire. In the same time it was aiming to create a public opinion and legal base to destroy the house structure without having to get an eviction title.

The legal obstacle on the way to an eviction title came up in 2016, when the Rigaer94 repelled a three weeks long major police action. Under public pressure, a court had declared the invasion in the house as illegal and did not recognize the lawyers of the owner which is, by the way, a mailbox company in the UK. Recent developements changed this condition from scratch. In the beginning of February a court decided that the police has to support this mailbox company to guarantee the so called fire security in Rigaer94. By this decision the owner is officially recognized and will now soon try to enter the house in company of a state expert about fire security and, of course, huge police forces. In similar raids against Rigaer94, the entering special police forces and the construction workers caused heavy damage to the building. It was always their goal to make the house uninhabitable before it could be evicted and luxury renovated.

We expect that the pretext of fire security will be used not only to remove our barricades but to legally raid the entire building and to evict flats to create permanent bases for the owners gang that will start to destroy the house from inside. As planned, the fire security is used now as a tool to terrorize the rebellious structures that took hold of the house more than 30 years ago and had been involved in many different social struggles as well as the defence of the area against state and capital. Generally we think that the importance of a combative community in combination with an occupied territory can not be underestimated. The Rigaer94 with its autonomous youth club and the self-organized, uncommercial space Kadterschmiede is a place for convergence for political and neighbourhood organization, giving not only home to struggling people but also the legacy of the former squatting movement and the ongoing movement against gentrification and any form of anarchist ideas. Many demonstrations, political and cultral events took its start from the house and, not to be forgotten, numerous confrontations with the state forces in the area were backed up by the existence of this stronghold. It’s for this political idendity that the Rigaer94 and the outreaching rebellious structures and networks are traumatizing generations of cops and politicians and thus has become a main focus of their aggression against those who resist. At the very moment when the last non-commercial, self-organized places in Berlin are being evicted, when the pandemic is used to spread the virus of control, exploitation and oppression, we have to take serious the threat of a very possible try to evict us in the upcoming days or weeks and therefore, we choose to continue getting organised through collective procedures to defend our ideologies and political spaces. However, there is a political importance to continue fighting for all of our social struggles of the revolutionary movement also outside of this house and not to let those in power to intervene in our political agendas and resistance.

They might evict our house but they will not evict our ideas. To keep these ideas alive and add fuel to them we invite everybody to come to Berlin to send the city of the rich to chaos. We call for any kind of support from now on, that can help us to prevent the destruction of Rigaer94. But if we lose this place to the enemies, we are willing to create a scenario without winners.

Rigaer94

for more information check https://rigaer94.squat.net/

and follow us on https://twitter.com/rigaer94

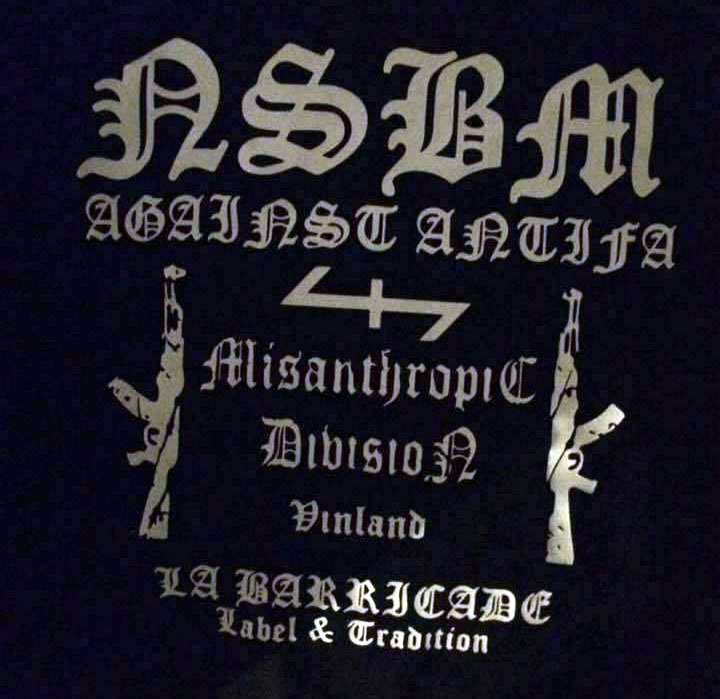

On February 2, the Canadian Anti-Hate Network published an article detailing the links between Steve Labrecque, alias “Steve Rebel,” alias “Chtev,” who we’ve mentioned before, and the local NSBM (National Socialist black metal) label La Barricade, which for a number of years now has been one part of the scummy underbelly of Québec’s musical counterculture.

For obvious reasons we’ve been paying attention to the tiny neo-Nazi/NSBM milieu for quite a while,[i] if only because it is close to the RAC (Rock Against Communism) scene, the band Légitime Violence, and the Québec Stompers bonehead gang, the incubator for the neo-fascist groupuscule Atalante. Our previous articles about Atalante and its sympathizers have clearly established the roots of Atalante’s key militants and their entourage in the “white power” and neo-Nazi subculture in the Québec City region, the pitiful denials of the key parties notwithstanding; they, of course, prefer to present themselves as “revolutionary nationalists” or sanitized fascists of the allegedly more presentable Italian variety.

While the Canadian Anti-Hate Network article served to shed some light on the key role of Steve Labrecque in this tiny milieu, it overlooked other key people who have been responsible for the distribution of Nazi clothing and accessories in far-right subcultural circles in Québec for many years now. It also passed too quickly over Misanthropic Division, an important network whose “Vinland” section[ii] is closely tied to the La Barricade label and acts as a link between this little band of local neo-Nazis and the Ukrainian Azov Battalion, which is broadly understood to be a key element in the militant and military vanguard of the international neo-Nazi movement.

This article, which was already in the works when the Canadian Anti-Hate Network published theirs, could be thought of as a “another step” beyond what they have written, which we do encourage you to read.

Warning: this article reproduces posts from social media accounts that are explicitly racist, antisemitic, and homophobic and celebrate Adolf Hitler, the Nazi regime, and the Holocaust.

///

As the Canadian Anti-Hate Network article indicates, Steve Labrecque (alias “Chtev,” a member or former member of the black metal bands Hollentur, Neurasthene, and Holocauste) seems to be the most recent addition to the group Légitime Violence, joining his friend and colleague Félix Latraverse (alias “Fix”; Neurasthene and Hollentur), alongside Raphaël Lévesque and Benjamin Bastien (Québec Stompers, Atalante), and the band’s new drummer, William Tanguay-Leblanc (about whom our comrades in Québec Antifasciste posted in November 2019).

Légitime Violence, 2020: (left to right) William Tanguay-Leblanc, Steve Labrecque, Raphaël Lévesque, Félix Latraverse, Benjamin Bastien

The direct link between La Barricade, Labrecque, and Légitime Violence is confirmed by, among other things, the release of a “tenth anniversary” Légitime Violence cassette in 2019.

A quick look at the La Barricade[v] Instagram[iii] and Facebook[iv] accounts reveals that Hollentur[vi], Steve Labrecque’s[vii] main project, is the label’s flagship band, which suggests a hypothesis we share with the Canadian Anti-Hate Network, that Labreque is the label’s main manager. Research at the registraire des entreprises indicates that in 2013 Steve Labrecque, now residing in the Beauport borough in Québec City, registered a “commercial printing” company that remains active today.

A t-shirt designed and distributed by La Barricade: “NSBM Against Antifa—Misanthropic Division Vinland—La Barricade—Label & Tradition”

We’ve previously discussed the band Folk You!, where Steve Labrecque rubbed shoulders with Kevin Cloutier, who was formerly a member of the bonehead gang the Ste-Foy Krew and the guitarist in Dernier Guerrier.

Kevin Cloutier (left) and Steve Labrecque (right): note the “1488” tattoo on the latter’s knuckles.

La Barricade, apparently under Steve Labrecque’s tutelage, also operates a basement studio in the Québec City region, where, among other decorative touches, we find the Misanthropic Division flag bearing the slogan “Töten für Wotan” (Kill for Odin).

A detailed FOIA Research article published in January 2019 presents the Misanthropic Division and its raison d’être as follows:

The Misanthropic Division is a world-wide neo-Nazi network, which in 2014 emerged in Ukraine, some of whose members fought as mercenaries against pro-Russian separatists in the war in Donbass. The Misanthropic division is closely linked to the neo-Nazi Azov Battalion, now part of Ukraine’s National Guard. It fights for the independence of Ukraine—both from Russia and the European Union—with the goal of establishing a Nazi state.

Amnesty International accuses them of serious human rights violations. The division maintains networks in Europe, USA, Canada, South America and Australia, which are also used to train and recruit fighters. (our italics)

Its members are considered racist and prone to violence. Among other things, they glorify National Socialism and the Waffen-SS. The Misanthropic Division is using a logo that is inspired by the Totenkopf (death’s head) symbol that was one of the most readily recognized symbols of the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS).

. . .

According to research by Belltower News, the Misanthropic Division recruits members from the international national-socialist-black metal (NSBM) scene. Liaison persons are the neo-Nazi Hendrik Möbus, convicted of murder, Alexei Levkin, singer of the band M8l8th and organizer of the NSBM festival Åsgårdsrei, and Famine, singer of the French black metal band Peste Noire. There are further connections to the Identitarian Movement and to the extreme right-wing party Der III. Weg.

Reading this article makes clear that the local partisans of the NSBM scene connected to the La Barricade label, who circulate around Légitime Violence and Atalante, of which Steve Labrecque is a key figure, are connected by the Misanthropic Division to an international neo-Nazi network and to the Azov Battalion, a white supremacist paramilitary formation that recruits members from everywhere in the Western world, with the goal of establishing a Nazi state.

Note that “Vinland,” historically related to Newfoundland, where the Vikings landed in the eleventh century, is a term applied by Odinists and others who fetishize Viking culture to North America, or, at least, to the northeast section of Canada and the US, and, as such, to the territory of Québec.

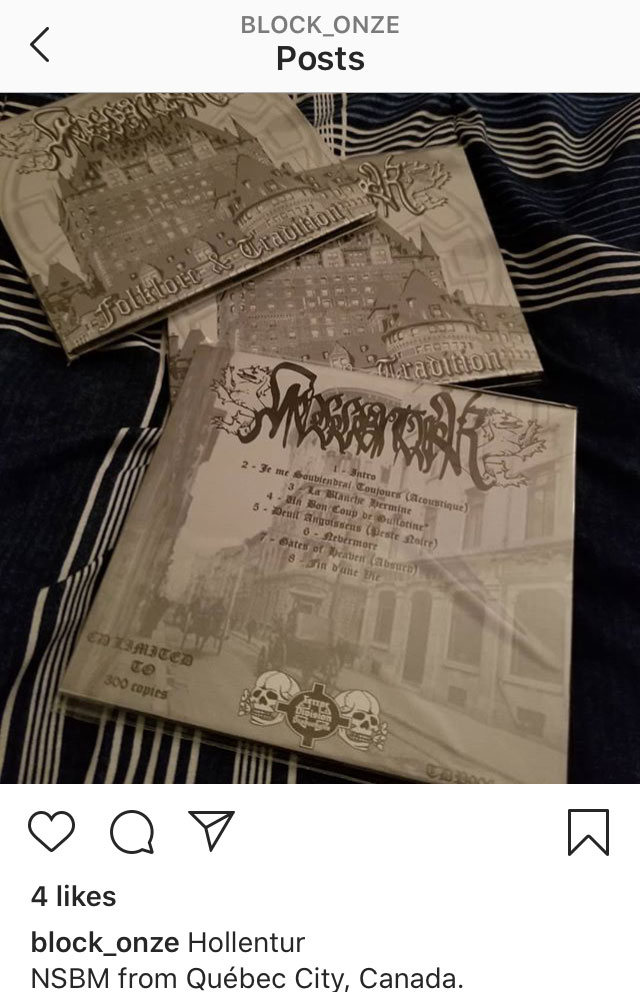

Another individual close to the La Barricade project, who the Canadian Anti-Hate Network does not mention in its article, is Philippe David , alias “Affreux Crapaud,” “Block_Onze” on Instagram, and “Phil Block Onze” on Twitter, one of the most uninhibited neo-Nazis of the entire Québec fachosphere! For a start, the pseudonym “Block Onze” is a direct reference to the building at the Auschwitz concentration camp where the Nazis tortured and shot thousands of detainees during World War II.

It is difficult to determine with any certainty exactly what role Philippe David plays as the La Barricade label or in the maintenance of the Misanthropic Division Vinland project[viii], but his Twitter[ix] and Instagram accounts make it clear that he has been a fervent promoter of the project since 2015, and that he has actively encouraged people to buy the crap distributed by Misanthropic Division and La Barricade, and did so until at least 2019.

Phil David promoting merchandise distributed by La Barricade and Misanthropic Division Vinland on his personal Twitter account.

Phil David promoting the Hollentur record distributed by La Barricade on his personal Instagram account.

|

|

|

|

|

|

We could, with good reason, ask why Twitter, which frequently boasts that it does not tolerate hateful discourse, has yet to ban or seriously sanction a user like Phil David, who has been using the platform to disseminate messages and images explicitly celebrating the Holocaust. In spite of its prevarications, Twitter has proven to be very tolerant of Nazis, white nationalists, and a legion of alt-right trolls, who, more or less discreetly, proliferate on the platform.

Phil David’s social network includes a fair number of known members of Québec’s neo-Nazi circles, going all the way back to the bonehead gangs the Ste-Foy Krew (Québec City; an outgrowth of the Fédération des Québécois de souche) and Strike Force (Montréal), active in the early 2000s.

Pool party on Phil David’s Instagram: (left to right) Pascal Giroux, Sébastien Moreau, Steve Labrecque, Mikaël Delauney, and Ian Alarie.

We can also see Steve Labrecque (kneeling in the back), Sébastien Moreau (centre), Ian Alarie (bottom right), Pascal Giroux (crouching on the left), and Mikaël Delauney (in the black t-shirt).

Sébastien Moreau, an old-school Nazi bonehead and member of the Ste-Foy Krew, who has caught the attention of the media more than once, has long been a person of interest on antifascist websites. He is best known for his entryist association with the Parti indépendantiste, a project that remains on the far right, with Alexandre Cormier-Denis, of Horizon Québec actuel, having been its candidate in a 2017 by-election.

Sébastien Moreau with his friends Raymond Jr. and Kevin Cloutier, from the neo-Nazi band Dernier Guerrier (Photo: Québec FachoWatch)

Ian Alarie is a basic NSBM enthusiast found at numerous Atalante actions, and who even turned up with the Soldiers of Odin in Montréal, on May 12, 2018, wearing… a La Barricade/Misanthropic Division Vinland t-shirt.

Alarie (right), Phil David (centre, wearing a Misanthropic Division t-shirt), and Étienne Chartrand (second from the left; a former member of Strike Force, the Fraction Nationaliste, and the Ste-Foy Krew).

It would seem that Pascal Giroux, another NSBM enthusiast, who was also present with the Soldiers of Odin, on May 12, 2018, was involved in a scrap with antifascists, in 2019, outside of a black metal music festival in Montréal.

Mikaël Delauney was the subject of an article in Vice, in 2018, based on his close relationship with Atalante and his role in a company specializing in “historical re-enactments” for young audiences. There is certainly room for concern about the kind of history that neo-Nazis would favour re-enacting.

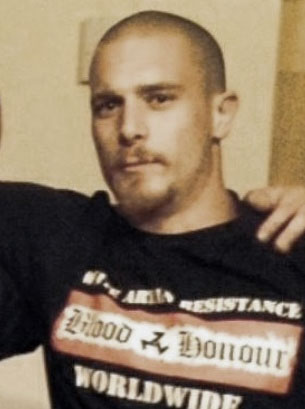

Fred Pelletier, an extremely hotheaded individual who also never bothers to hide his neo-Nazi sympathies, is another close friend of Phil David.

Fred Pelletier proudly sporting a Blood & Honour t-shirt. Blood & Honour is a neo-Nazi organization listed as a terrorist organization under the Canadian Criminal Code.

And here’s Phil David with Francis Hamelin, another regular around the neo-Nazi scene since the early 2000s.

A special shout-out to Sarah Miller, who recently became Jonathan Payeur of Atalante’s fiancée.

One day, Sarah Miller had the bright idea of tattooing “1488” across her chest in three-inch letters.

Finally, let’s take a look at Gabriel Marcon Drapeau’s role, which is touched upon in the Canadian Anti-Hate Network article. This guy, who Fascist Finder comically portrays as a rabid dog, seems to have updated his Linkedin account, which until very recently indicated his employer to be the “the Barricade NSBM label.”

Gabriel Marcon Drapeau poses for his Facebook profile photo in front of a Misanthropic Division Vinland flag.

Marcon Drapeau’s current Linkedin page indicates that he is now working for “Vinland Striker,” where he continues his career in sales of clothing and accessories of a Nazi character, including flags bearing the image of Adolf Hitler. See below a sample of the merchandise he promotes on his personal Facebook page and on the distributor website[x]. We have no idea why Marcon Drapeau no longer operates his distribution under the Misanthropic Division Vinland/La Barricade banner, but it seems that he has maintained his privileged relationship with the French distributor of neo-Nazi clothing 2YT4U.

Note in passing the curious fact that Atalante militants and sympathizers tend to wear the t-shirts Marcon Drapeau distributes.

Louis Fernandez, a key Atalante militant, who was sentenced to fifteen months in prison in December 2020 for criminal assault, sporting a Joan of Arc t-shirt distributed by Gabriel Marcon Drapeau.

Montréal-based Atalante militant “Jean Brunaldo” wearing a KKK-inspired t-shirt distributed by Gabriel Marcon Drapeau.

Atalante sympathizers Heïdy Prévost and Vivianne St-Amant wearing an ecofascist t-shirt distributed by Gabriel Marcon Drapeau.

Atalante militant Sarah Miller wearing an ecofascist-inspired t-shirt distributed by Gabriel Marcon Drapeau.

Well then… Jonathan Payeur sports ANOTHER ridiculous t-shirt distributed by Gabriel Marcon Drapeau. You certainly would be well advised to remain hidden

Nothing indicates that the Misanthropic Division Vinland project that is connected to the NSBM label La Barricade is anything more than a group of neo-Nazi buddies in the grip of romantic adventurism, but there is also nothing to indicate that this project couldn’t serve as a recruiting centre for the international neo-Nazi network or a fundraising operation for the Azov Battalion. It is evident that at a minimum these neo-Nazi music and merchandise distribution projects play a substantial role in the micro-economy of the tiny neo-Nazi milieu in Québec and in increasing the reach of this revolting subculture.

We also can’t ignore the role these projects can play in turning young fans of black metal who are susceptible to the pull of Nazi alarmism into fanatics, with the programme always completely focussed on the extermination of millions of people who fail to meet the sickening bar these losers have set as their ideal of Aryan purity.

These detestable racists will live among us, be part of our society’s collective spaces, and continue their tawdry little activities with impunity as long as we continue to allow them to do so without raising any real resistance. It falls to our communities to flush them out and neutralize their toxicity.

As with any invasive and dangerous species, to uproot it you first have to recognize it.

///

If you have any information you’d like to share about the La Barricade label, the Misanthropic Division, or any of the individuals mentioned in this article, please write us at alerta-mtl@riseup.net.

[i] It is important that we acknowledge the work done before we existed by Anti-Racist Action Montréal, the webzine Dure Réalité, and Québec Facho-Watch.

[ii] Note that “Vinland,” historically related to Newfoundland, where the Vikings landed in the eleventh century, is a term applied by Odinists and others who fetishize Viking culture to North America, or, at least, to the northeast section of Canada and the US, and, as such, to the territory of Québec.

[iii] https://archive.md/JUB9G

[vii] https://archive.vn/oqaj0

Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

Black and white PDF for printing (imposed)

Colour PDF for reading

It was winter 2020 and in the aftermath of the most inspiring anti-colonial uprising of my lifetime, I read Rattachements[1] (Re-attachments in English) and Inhabit[2]. The trains had started up again across the country, and COVID-19 was starting to reorder our lives mere weeks after we had been doing our small part to help shut down Canada. In and around Tio’tia:ke (Montreal) where I live, there were many Indigenous-led initiatives, including solidarity rounddances that blocked traffic downtown, and of course the month-long blockade of the railway tracks that run through Kahnawá:ke. On and around the island, the engagement of settlers in #ShutDownCanada took a number of forms including clandestine sabotage of rail infrastructure, demos and vandalism of RCMP property, and multiple rail blockades, one of which lasted a few days.

Coming down off of these events, it was especially jarring to read the proposals in Inhabit and Rattachements. Both texts are representations of political thought coming out of communities in the US and Quebec that are heavily influenced by the writings of the Invisible Committee in France and European Autonomist movements. This political tendency is sometimes labelled tiqqunist, appelist, or autonomist. It is a political orientation that has a significant amount of sway among a segment of those who were engaged in the settler-initiated[3] portions of the organizing in Montreal last winter, and these two texts seem to be important reference points for these people. Unfortunately, the onset of COVID-19 stifled what could have been an opportunity for deeper analysis of some of the political differences between those of us who organized together that winter. I would like to clarify my disagreement with the anti-colonial strategy, or lack thereof, put forth by Inhabit and Rattachements. I hope that in future broad coalitional moments of solidarity like last winter, we might be able to better understand where our potential for collaboration could break down. I also hope that critical engagement with the analysis proposed by these texts will limit the extent to which it influences the contours of settler-initiated anti-colonial solidarity in years to come.

Taking issue with dominant currents of environmentalist action (on the one hand activists who ask the government to take action to save the environment, and on the other individuals changing their consumption practices to do the same) the writers of Rattachements propose a new approach to dealing with the ecological crisis and colonial capitalism. This new approach is one of building an “ecology of presence” through the construction of communes[4]. The writers see the project of reconnecting to that which “has been torn from them” as both material and spiritual. They wish to truly inhabit land from which to attack the machinery of capitalism while also building new forms of life there. Foundational to their understanding of the problem is an assertion that they did not choose to be thrown into a world bent on its own destruction, a world structured by colonial capitalism[5], wherein their “affects are captured” and their connection to the land has been severed.

The writers forward that “[d]efending the land necessarily means learning to inhabit it, truly inhabiting it necessitates defending it.” In doing so they assert that their reconnection to the land is a precursor and integral part of anti-colonial struggle. An “ecology of presence,” they write, can be found in the connections between Indigenous peoples and their territories, including the Zapatistas’ resistance against the Mexican government and the material and territorial autonomy of the Kanienʼkehá꞉ka. However, the writers are rejecting an analysis of social position from jump. They appear to not think that the position of subjects within systems of domination is relevant to their analysis or strategies of resistance to those systems. But the writers are nonetheless settlers speaking to (mostly) other settlers. The abstraction they employ is thus dangerous, as they go on to say that “it is when communities affirm that they themselves are part of the territory, of this forest, of this river, of this piece of the neighbourhood, and that they are ready to fight, that the political possibility of ecology appears clearly”. This statement can easily be seen as a call for settlers to understand themselves as belonging to the land in order to defend it, or at the very least, on a level playing field with Indigenous people when it comes to assertions of what the future of land in this place should resemble. Whether or not this is the intention, this opens the door to settler self-indigenization being understood as a decolonial strategy. In a settler colonial society like Quebec or Canada, the state exists in large part to secure settler access to land, and Indigenous people are always threats to that access. This is both the history and present of all settler societies. We need not look far to find examples where settlers relating to the land in a way that resembles Rattachements’ “ecology of presence” has already been put into practice effectively against Indigenous people.

Take, for example, the story of the white hunters in Mi’kma’ki (the Chic Choc Mountains in Gaspésie, specifically) who in 2004 had already grown frustrated about the incursion of logging in the area and who, having hunted on the land for quite some time and feeling rather connected to (even “of”) the territory, were faced with a new threat: the establishment of a “Mi’kmaq-controlled area which would offer outdoor activities for a fee” (a “pourvoirie”). This new project threatened their ability to hunt for free. In response to this, while meeting in a “communal tent” on the territory, the white hunters concocted a plan to identify as Indigenous in order to help add legitimacy to their claims of connection to the land. They founded an organization which would come to be named the Metis Nation of the Rising Sun, and successfully prevented the establishment of the pourvoirie. This story is not an outlier in our area, rather merely one example of a widespread phenomenon wherein settlers, feeling very attached to the land they are living on (and maybe even having some communal inclinations) feel moved to defend their control of it from threats that include Indigenous people who have their own pre-existing claims and relations to the same land. Often, this involves claiming an Indigenous identity, but it need not necessarily. What continues to be crucial for the advancement of settlement is the ongoing procurement of land by settlers and the entrenchment of the idea that this is our land, whether the possession is property based (I have the deed and so this is mine) or spiritual (I know the land, I feel connected to the land, and so I belong here).

Looking to other settler colonial contexts, we can see more examples of the risks of communal settlement undertaken with radical political aims. The Kibbutz movement in Palestine, for example, is a story of self-organized communes set up from the early 1900s onward, beginning with the second wave of Jewish settlers fleeing pogroms from Eastern Europe. The settlers of the first Kibbutz had anarchist ideals of egalitarianism, rejected the “exploitative socio-economic structure[6]” of the farms established by the first wave of settlement, and hoped to undermine the developing capitalist economy with their communes. They sought to establish “a cooperative community without exploiters or exploited[7]“, and did so in 1910 after gaining access to land “which had recently been bought by the Palestine Land Development Company from the Jewish National Fund.[8]” This first farm was such a success that “before long, kvutzot were being set up wherever land could be bought.[9]” These communes, while viewing themselves as a viable alternative and considerable threat to the capitalist mode of production, were also serving the Zionist settlement of Palestine. Today they are commonly understood as an important part of Israel’s national story, and approximately 270 settlements still exist (despite their internal organization and anarchist character having shifted significantly) in occupied territory. It is clear that while the anarchist and anti-capitalist ideals of such projects may be inspiring, the settler colonial context calls for attention to the impacts of settlement on Indigenous peoples, not merely the ideals or internal politics of communes[10].

Rattachements emerges from and endorses an understanding that settlers too have been dispossessed – of connection to land, of spirituality and knowledge. It leans hard on this claim to try to get other settlers to feel moved to action. The zine, written within and circulating among social circles dominated by white settlers with varying radical politics, posits that a solution to the ecological crisis lies in these (again, primarily settler) milieus’ ability to create communes. These communes will then be able to establish material and political autonomy by rendering spaces (land, wastelands, buildings, churches, houses and parks) “liveable”[11]. In other words, they propose to settle and squat, communally, the land, whether it has already been built on by other settlers or not, asserting that this is a strategic necessity rather than merely a lifestyle choice.

I too believe that capitalism is a system which alienates us from each other and the living beings we depend upon. And yet I believe that we must be more specific: colonial capitalism has created a country wherein, by and large, settlers own land, and have the resources and relative freedom to build a variety of relationships with it. This comes at the expense of Indigenous peoples, who have been dispossessed of their land, and the languages, cultures, and spiritualities that emerge from and inform their relationships with that land. Rattachements suggests that a crucial part of the anti-capitalist/anti-colonial ecological struggle is shifting settlers’ affective and spiritual relationships with the land in a context where our material relationship with the land – one of ownership of that which has been stolen — remains unchanged and fundamentally colonial. A group of settlers buying a communal house together outside the city as part of a strategy of revolutionary ecology has little to nothing in common with Indigenous peoples reoccupying their traditional territories. The latter is a direct disruption of colonial development projects and environmental destruction and is recognizable as part of a lineage of Indigenous resistance to displacement and genocide.[12] The former misrecognizes itself as somehow sharing something with that lineage, when in fact it is possible because of, and shares much more with, generations of encroachment and expansion by settlers.

Absent from the program of ecological struggle proposed by Rattachements is an explicit call for the return of land to Indigenous communities. Instead, they call implicitly for an increased presence of their (settler) milieus on that land, in part in order to potentially support Indigenous struggles. Despite the acknowledgment that land has been stolen (and the lauding of Indigenous relationships to land as ones to look to as examples for the readers of the zine) what is missing is the proposition that “Land Back” in the literal, material sense, is an important piece of the ecological struggle, and one to prioritize leaps and bounds above settlers going back to the land. In the Land Back Red Paper released in 2019 by the Yellowhead Institute, the writers tell us that “the matter of Land Back is not merely a matter of justice, rights or ‘reconciliation’; Indigenous jurisdiction can indeed help mitigate the loss of biodiversity and climate crisis. […] Long-term stewardship of the land allows for constant reassessment, planning, and adaptation.” This leads to an efficacy of protection of biodiversity and hope against climate change thanks to the culturally specific world views passed intergenerationally through a presence with and in defense of the land.[13]

It must not be seen as a necessary precondition for decolonization that settlers develop relationships (spiritual or affective) with land that we occupy. Settlers deciding to prioritize building these new relationships with the land does not bring us closer to decolonization. Focusing on settlers’ spiritual or affective relationships to the land as an important part of anti-colonial struggles sidetracks and warps our ability to focus on the much more central problems of settler colonial Canada. The dispossession of Indigenous peoples’ lands is a partial but crucial piece of struggling against settler colonialism and climate change. Regardless of the politics of the settlers, our relationships with land are most often built through a tactic of land ownership, due to the relative ease of access to the financial means or social connections that allow for this. I am thinking, for example, about the many collective land projects that have been initiated by radical settlers in so-called Quebec, which all involve owning the land. To think of building a land-based spirituality on a foundation of land ownership does not make sense, these relationships would be colonial, not revolutionary. In other words, the relationship between settlers and land must change primarily on a material basis, not a spiritual or affective one. Indigenous peoples have articulated that “Land Back” will give them the power to rebuild knowledge, languages, culture, and autonomy. This is the substance of decolonization; it is crucial that Indigenous peoples be free to develop and regain their relationships with the land rather than settlers taking it upon ourselves to do it in their stead.

In Inhabit, a text coming out of appelist/tiqqunist/autonomist networks in the so-called US, the desire for territory is expanded.The goal articulated in Inhabit is the extension and multiplication of the isolated communes of Rattachements. Yet unlike Rattachements, whose authors claim to be committed to their own understanding of an anti-colonial politics, Inhabit does not articulate an anti-colonial politic at all. This is not necessarily surprising, as anti-colonial politics seem to be less present in settler radical milieus in the US than in Canada, but it still matters.[14] “Our goal”, they say, “is to establish autonomous territories—expanding ungovernable zones that run from sea to shining sea. Faultlines crossing North America leading us to providence.” Like the westward expansionists of yore, the writers of Inhabit posit a better way to use the land and suggest that pockets not yet taken up in service for their revolution be transformed in their image. In other words, one can read the writers of Inhabit as promoting their vision of Manifest Destiny: the expansion of land use in their vision, faultlines moving unimpeded across a vast and unclaimed North America. Perhaps following the paths of the railroads that came before?

Inhabit’s authors seem unable or unwilling to engage with settler colonialism. With the exception of the mention of incidental interaction between settlers and Indigenous families in contexts where they are already comrades, race and colonialism are invisible in their text. The authors’ unwillingness to engage with the larger collectivities of Indigenous life and their settler colonial context betrays their colonial understanding of the land itself. In proposing territorial expansion without concern for the claims to land that cover this continent already[15], Inhabit calls to its readers with imagery of the settler state national project – from sea to shining sea: “Build the infrastructure necessary to subtract territory from the economy,” they urge. But the land has never been just territory, and settlers occupying it has more often looked like removing Indigenous peoples than subtracting it from the economy. One need only look to the southern US to see how, for example, white people squatting “vacant” land was an intended consequence of the process of allotting Indigenous people land far from their communities. The US banked on the fact that these communities would be unable to prevent squatters from setting in and taking possession. “Rent a space in the neighborhood. Build a structure in the forest. Take over an abandoned building or a vacant piece of land.” Inhabit repurposes thought and strategies from contexts highly unlike their own (squatters movements in europe, for example) and tries to implement supposedly liberatory strategies for “inhabiting” space that merely further entrench settler access to and control of land.

In an October 2020 report-back called Chasse à la chasse[16] (translated as Hunting the Hunt in the English version published by Inhabit’s “Territories” newsletter), the writers (based in Quebec) give an account of their time spent supporting Anishnabe communities fighting for a moratorium on moose hunting in their territory. They conclude their summary of the situation with the following reflection: “It would be an illusion confining one to weakness to think that we cannot be and appear other than as illegitimate settlers, regardless of ‘how’ we intend to inhabit what is left of the world.”[17]

It is surprising to me that one of the most pressing takeaways from organizing in solidarity with an Indigenous community would be the possible escape from settler “identity” it uncovers. It seems to me that the fear of being seen as an “illegitimate settler” is what motivates some of their rejection of social position and in turn undermines their analysis. I don’t intend to say that the authors have nothing to contribute to anti-colonial struggle because they are settlers. Rather, I disagree with the importance being placed on not being perceived as settlers, instead of on evaluating what is the most effective contribution they could make to anti-colonial struggle. Their position as settlers in a settler society is necessarily going to be an important piece of this evaluation. This rejection of social position is visible in Inhabit in so far as race and colonialism are made invisible. In Rattachements, it is only visible as a thing from which the writers flee. “Ecstasy: bliss provoked by an exit, a departure from what has been produced as our ‘self’, our ‘social position,’ our ‘identity.’” In a hurry to reject identity politics, and in conflating “identity” with an attention to social position, the writers remove the lens that would allow them to analyze our context more fully and accurately. In doing so, they doom themselves to a flat and limited approach that says that if it is strategic and possible for Indigenous people to build territorial autonomy, it must be just as strategic, possible, and subversive, for settlers to do the same.

The St. Lambert rail blockade was a multi-day action called by and mostly attended by settlers last winter in the context of #ShutDownCanada. It was an opportunity for a proactive and explicit explanation of why we as settlers thought it important to respond to the call for solidarity actions in the way we did, and an encouragement of other settler radical milieus to do the same. This could have been very valuable in a context where some settler supporters were hesitant to propose or participate in settler-initiated actions[18]. Unfortunately, this proactive communication approach was not taken for a variety of reasons, including lack of political cohesion amongst the people organizing the action. In the end, communication coming out of the camp opted for vague language about who was there and who was being spoken to and missed an opportunity to speak as settlers to other settlers about what we could do to intervene[19]. Obfuscating our position made it easier for the mainstream media to use the fact that we were not Indigenous as a “gotcha” moment which helped them attempt to turn public opinion against us without using overtly racist tropes. Our lack of clear analysis also left space for Premier Francois Legault to separate us from the other blockades because we did not explain how we saw ourselves in relation to them. Of course the cops knew all along the demographics of those in attendance and acted accordingly. There were no tactical advantages to this approach, and we lost the opportunity to put forth clear, decisive analysis as to why other settlers should take the risks we (and many Indigenous communities) were taking at that time to shut down Canada. I worry that an avoidance of addressing head on issues of social position and the role of settlers in anti-colonial struggle may lead us to make similar choices in the future.

Inhabit and Rattachements share a desire to produce affect in their readers which inspire them to see themselves as full of power and possibility. Toward this end, they encourage readers to reject guilt or sacrifice and to understand themselves as central protagonists in struggle. For Rattachements, this looks like encouraging their readers to see themselves as “neither victims” of “nor guilty” for the ecological crisis. This aversion to self-sacrifice, to being ready to give something up, means denying that settler colonialism and some other drivers of the crisis continue to benefit us. This is the preemptive evasion of potential guilt for being a settler – we must not understand ourselves as the subjects for which the genocidal removal of Indigenous people from their land is ongoing. The impulse is tied to a rejection of identity politics, and while I do not suggest to instead embrace a demobilizing guilt in the face of the past and present horrors, I think it is both a strategic and ethical imperative to refuse to ignore the conditions that produce this guilt. When we acknowledge the kinds of lives that settler colonialism continues to produce for settlers and try to find the causes for the clear disparity, we equip ourselves with the knowledge of our context necessary to change it in effective ways. When we flee the feelings produced by this disparity by rejecting a label, we may come to believe we can think or magic our way out of real structures. It is the conditions that need to be fought, not the emotions they produce.

The authors of Inhabit and Rattachements might think that rejecting, on the basis of demographics, their respective strategies of territorial autonomy or of building material autonomy in communes on the land is essentially a refusal to build power—a concession to the demobilizing effects of ally politics. On the contrary, I think this rejection is both an ethical and a strategic choice, from which we must necessarily develop a stronger and more anti-colonial revolutionary strategy. It does not weaken our movements to turn away from building territorial autonomy for primarily settler communities if what we turn towards is a greater focus on the continued rebuilding of territorial autonomy for Indigenous peoples we seek to be in struggle with. What is required is to not see settlers as the central subject of revolutionary anti-colonial struggle, and to recognize that the positions from which we struggle differ and thus the paths we take must also differ. Any serious analysis of Canadian settler colonialism will see the hundreds of years of Indigenous struggle against capitalism and the state as relevant and in many ways determinant of the chances of these communities’ potential success at building territorial autonomy. This same analysis will note the difference between this history of struggle and that of radical settler movements in so-called Canada.

If we talk about territorial autonomy in a serious sense, we will know it is far more than “a network of hubs” we’ve rented, squatted, or built in the forest, or a constellation of communal houses in the country. Territorial autonomy, if seen as a strategy for the destruction of capitalism and the state, includes the long term work of developing zones where cops cannot go, where the means to sustain and reproduce those who live there can be found, where a large group of committed and connected people of all ages has the means and the need to defend that territory, over generations. We can look to where this work has already been done for hundreds of years to see examples: Wet’suwet’en territory, Elsipogtog, Barriere Lake, Six Nations, Tyendinaga, Kahnawá:ke, and Kanehsatà:ke. This work has by and large not been done for hundreds of years by non-Indigenous communities – we are starting from zero, and thus even if prioritizing our own territorial autonomy seemed ethical, it would not be likely to be strategic because settler communities in a settler society have much less structural conflict with the colonial system. It does not make us weaker to prioritize the fight for the territorial autonomy of communities of which we are not a part. It makes us stronger, if by doing so we build relationships that contribute to revolutionary contexts in which the goals of settler revolutionary networks converge with those of anti-colonial Indigenous groups. Toward a stronger potential for joint struggle against the colonial state.

Our environmental politics must foreground material responses to the dispossession of Indigenous peoples’ land, for the sake of the planet and as part of a broader commitment to anti-colonial politics. It is dangerous to slip towards a “back to the land” politics, as Rattachements does, because these approaches and projects at best sidetrack us, and at worst set the stage for the development of twisted settler claims to Indigenous land. These kinds of claims will shatter the relationships we should seek with anti-colonial Indigenous allies, and risk strengthening settler reactionary tendencies that we should be fighting. If we see ourselves as aiming to engage in joint struggle with Indigenous communities against the colonial state, we will know that what makes our movements stronger is when our comrades are strong, and our relationships with them are strong.

If we focus on the material realities of settler colonialism and the real ways in which it continues to structure our lives, options, and resources, we can develop more effective strategies by asking what our differing social positions allow and disallow, and how we might put these differences to work for common goals. Mike Gouldhawke explains that “people think of settler as a personal identity but it’s more about a categorical relation between a social subject and settler states”[20]. As La Paperson says, the term settler (and native, and slave) describe “relations of power with respect to land. They sound like identities, but they are not identities per se.”[21] Instead of an attempt to flee these labels, we should put our time to better use and focus on changing the conditions producing those relations of power.

Social position as the sole lens of analysis for developing revolutionary strategy is of course insufficient. It matters deeply how people, no matter what their lives are like now, want the world to look like in the future. However, we need to be able to see and understand the different material realities of those around us in order to have any hope of those realities changing in the world we want to build together. Seeing these realities for what they are, and why they are, shows us that the relationships settlers build with the land are far less important than the ones we dismantle. It is clear that supporting the resurgence of Indigenous territorial autonomy needs to be a greater priority than building a territorial autonomy of our own. The question becomes how to build and sustain formations that can offer long term support and solidarity to Indigenous people struggling against the colonial state, and how best to cultivate a politics that will continue to respond to the shifting contexts, relationships, and terrain of that joint struggle toward self-determination and an end to capitalism, colonialism, and Canada.

[1] Rattachements is available in French here: https://contrepoints.media/fr/posts/rattachements-pour-une-ecologie-de-la-presence , and in English here: https://illwilleditions.com/re-attachments/

[2] Inhabit is available here: https://inhabit.global

[3] To be clear, for myself and many others, we saw ourselves as “initiating” specific actions in response to explicit calls for such activity, in response to changing contexts that we thought demanded it, and in at least the case of the rail blockades, very clearly directly inspired by already ongoing Indigenous initiatives. I use the phrase “settler-initiated” not to take credit for the events of what was very clearly an Indigenous-led movement, but rather to note that there is a real difference between those actions seen by supporters and adversaries as taken by Indigenous communities and those recognized as settler solidarity actions.

[4] It should be noted that the communes they describe are essentially nice places to live where people share meals and daily activities and talk to each other, and not necessarily communes on a scale where they would produce meaningful reorganizations of the economy or social reproduction. It is reasonable to assume that shift in scale is desired.

[5] Which they call colonial-modernity.

[6] Page 17 of A Living Revolution: Anarchism in the Kibbutz Movement by James Horrox

[7] A Living Revolution 18

[8] A Living Revolution 18

[9] A Living Revolution 19

[10] Another example of this kind of communal settlement that I learned about during the writing of this text is the Finnish socialist settlement of Sointula, located on the territory of the ‘Namgis First Nation. The village was established in the early 1900s on so-called Malcolm Island in British Columbia.

[11] The English translation uses the word habitable rather than liveable.

[12] https://briarpatchmagazine.com/articles/view/100-years-of-land-struggle

[13] I do not wish here to forward a romanticized view of Indigenous peoples as never exploiting the land, as the Red Paper cautions against doing on page 60. Rather I wish to remind us that without Indigenous peoples’ ability to steward the land, the destruction of capitalism alone would still leave us without the intergenerational knowledge to care for it in effective ways. https://redpaper.yellowheadinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/red-paper-report-final.pdf

[14] Conversely, critiques of anti-blackness and slavery are often not well integrated into analysis coming out of settler radical networks here in Canada compared to in the US. This makes it even worse that Inhabit also makes no reference to this kind of critique or analysis either.

[15] By pre-existing claims, I am referring both to Indigenous claims to land as well as longstanding claims by groups such as the Republic of New Afrika.

New Afrikans And Native Nations ( Roots of The New Afrikan Independence Movement ) – Chokwe Lumumba

[16] Available in French here: https://contrepoints.media/posts/chasse-a-la-chasse-recentes-mises-en-acte-de-la-souverainete-anishinabee , and in English here: https://territories.substack.com/p/hunting-the-hunt

[17] It is worth noting that the English and French versions differ somewhat significantly. Whether due to large errors of translation or intentional changes in anticipation of an Anglophone American readership, the closest sentence in the English version reads: “The question of how to inhabit concerns any living being in any given place.” This is a major difference.

[18] #ShutDownCanada was a massive, broad, and heterogeneous Indigenous-led movement. A large catalyst was the militarized RCMP raid on Wet’suwet’en land defenders protecting their home from Coastal Gas Link pipeline construction last winter. In that context, a number of explicit calls for solidarity actions were put out including by Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, and specific camps on the land such as the Gidimt’en checkpoint. Despite these very clear and explicit calls to action, I think that some of the hesitancy of some sympathetic settlers to participate in settler-initiated solidarity actions came from a belief that all actions needed to either be Indigenous-led or explicitly endorsed or approved by an Indigenous person. I believe Indigenous critiques of the ways that settlers participate in anti-colonial organizing are important. I believe that it is crucial to consider how one’s actions might be perceived by or have consequences for Indigenous communities when planning solidarity actions. However, sacrificing basic security principles of “need to know” in order to obtain an Indigenous stamp of approval on a risky settler-initiated action seems like an especially egregious form of tokenism. That our organizing communities in Montreal are often majority or exclusively made up of settlers is something to be examined and addressed on a more foundational level rather than attempting to hide it by seeking an endorsement of our choices after the fact. I could be wrong, but my assumption from this winter was that some settlers sympathetic or supportive of #ShutDownCanada were worried about the risks of participating in solidarity actions and used the fact that some actions were settler initiated to avoid having to take risk and join the blockade. I think this is unfortunate and is something that must be changed in part by clearer anti-colonial analysis coming out of settler networks.

[19] Limited record exists of other speeches to the media, but this is one example. https://contrepoints.media/en/posts/declaration-du-blocage-de-saint-lambert-declaration-from-the-saint-lambert-blocade

[20] https://twitter.com/M_Gouldhawke/status/1345150065103388673

[21] https://manifold.umn.edu/read/a-third-university-is-possible/section/e33f977a-532b-4b87-b108-f106337d9e53

Thoughts? Email: anotherword@riseup.net

From the Kanienkehaka Land Back Language Camp (Facebook)

January 26, 2021

As we approach our 6th month at Kanienkehaka Land Back Language Camp, we’ve hunkered down for the winter season.

We continue to build our school house, and adjust our camp as the weather changes. The Salmon River has frozen over, allowing us to enjoy the ice and the easier access it gives us to the other side of the river.

Our young people have been busy learning the Kaniehkehaka language, with our recent theme being about hunting, trapping and conducting ceremony.

Soon we will be focusing on the ice and the activies, hobbies and survival skills that come with all of its teachings.

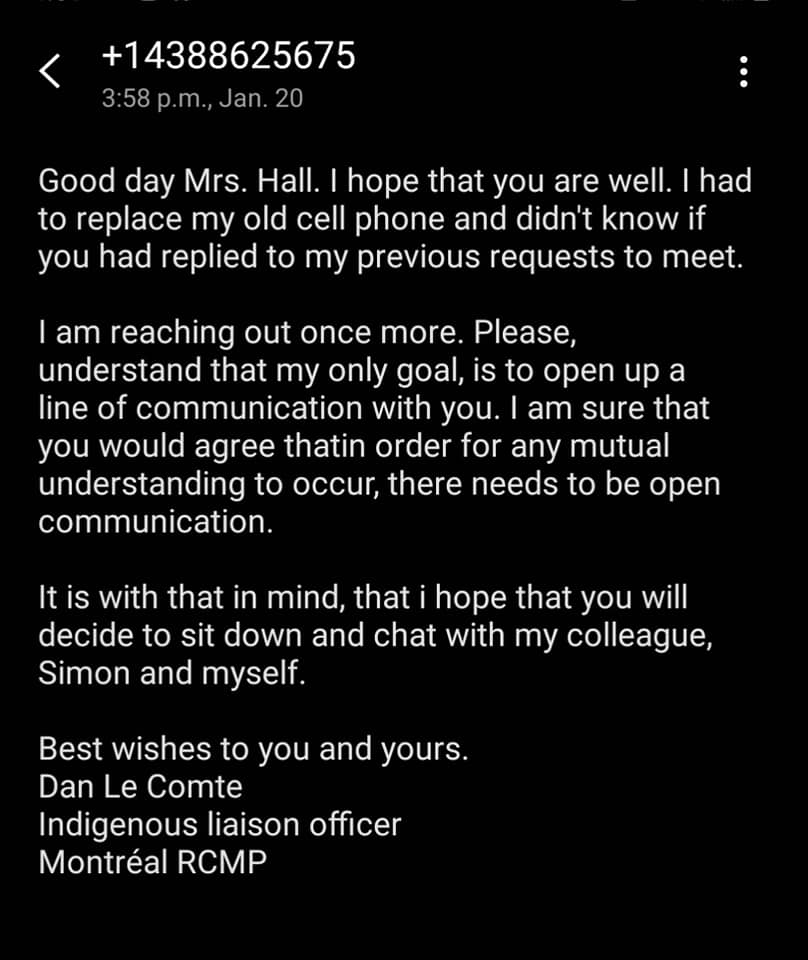

Recently we have had both the Surete Du Quebec and RCMP liasons reach out to the camp, asking for a sit down and inquiring on when we plan to leave. So far, no discussions or sit downs have been agreed upon with either agency.

Nia:wen Kowa to everyone who has donated to our GoFundMe, raised monies and/or continue to support our efforts at Kanienkehaka Land Back Language Camp.

You can donate to our GoFundMe at https://gofund.me/919caf4f

From Briarpatch Magazine

The handful of supporters in the sparsely-populated courtroom came there to bear witness and stand in solidarity with an Indigenous Elder who had just been tried for a second time and was now awaiting the verdict.

In December, B.C. Supreme Court Justice Shelley Fitzpatrick found Jim Leyden guilty of criminal contempt of court for breaching an injunction originally brought by Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC (TMX) in March 2018. The injunction is the line that TMX has drawn in the sand, so as to stifle any meaningful resistance at the company’s worksites throughout the province – including TMX contractors and subcontractors – and all along the pipeline’s path.

It was Leyden’s second conviction, with more than 230 people found guilty of breaching the TMX injunction since 2018. Those in court to support Leyden on December 9, 2020, were unsurprised by the verdict, but they were nonetheless outraged. Leyden’s conviction represents a new strategy by TMX and the Crown that skirts established Crown policy on civil disobedience and ruthlessly targets Indigenous land defenders.

The injunction is the line that TMX has drawn in the sand, so as to stifle any meaningful resistance at the company’s worksites throughout the province.

Leyden, 68, was sentenced for his first conviction in October, along with his two Indigenous co-defendants – Stacy Gallagher, 58, and Tawahum Bige, 27 – all of whom were in ceremony at the time of their August 2018 arrests. Fitzpatrick all but ignored Leyden’s health conditions, which would normally mitigate his punishment, and sentenced him, along with Gallagher and Bige, to the Crown’s recommendation of 28 days in jail, one of the longest sentences imposed against land defenders for breaching the TMX injunction.

During COVID-19, these sentences amount to solitary confinement, much harsher than normal detention conditions. Leyden, who already suffers from pancreatitis and a heart condition, and has been in and out of hospitals since his 2018 arrest, spent much of the time between his release and his second trial in the hospital dealing with health and heart impacts from multiple spider bites he got while in jail at North Fraser Pretrial Centre.

On New Year’s Eve 2019, Leyden and Gallagher were served with notices from the Crown that they were being charged, yet again, with criminal contempt for apparent activity at TMX’s Burnaby Mountain facility (Burnaby Terminal) in November and December of that year. But no arrests had occurred at the scene, which left Leyden and Gallagher wondering why they were being charged.

After reviewing the disclosure, it became evident that Leyden and Gallagher were being targeted by TMX and the Crown. Affidavits and video footage taken by TMX security personnel identified Leyden and Gallagher near the gates of the Burnaby Terminal on December 2, 2019. Additional footage also showed Gallagher in the same general location on November 15 and December 18, 2019.

Notably, each video clip showed Leyden and Gallagher surrounded by several other, mostly white land defenders. But no one else was charged by the Crown.

It’s well known that Leyden and Gallagher are part of a group called the Mountain Protectors which, among other things, monitors TMX work carried out at the Burnaby Terminal. (I am also a member of the group.) The terminal is also known as the “tank farm,” because of the giant oil storage tanks spread out over the side of the mountain that can be seen from several kilometers away. With permission and direction from traditional Elders of the three host nations – Tsleil-Waututh, Squamish, and Musqueam – Leyden, Gallagher, and others have engaged in ceremony and carried out monitoring activities from an Indigenous Watch House built in March 2018, which sits adjacent to the tank farm and is explicitly excluded from the TMX injunction despite its position atop the pipeline route.

Notably, each video clip showed Leyden and Gallagher surrounded by several other, mostly white land defenders. But no one else was charged by the Crown.

According to the website of Protect the Inlet, a Watch House (“Kwekwecnewtxw” or “a place to watch from” in the henqeminem language) is “grounded in the culture and spirituality of the Coast Salish Peoples” and is a “traditional structure they have used for tens of thousands of years to watch for enemies on their territories and protect their communities from danger.”

On the same day that Leyden was accused for a second time of violating the injunction, he and others were attempting to bring light to claims that TMX was improperly transporting contaminated soil from the tank farm to an industrial park in Port Coquitlam. The Mountain Protectors issued a press release a day earlier questioning whether the company was in violation of provincial contaminated soil regulations. Leyden can be seen in his disclosure footage talking to people Fitzpatrick referred to during his trial as “media types.”