Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

For more background information, check out this piece about who has been awarded the new contracts and a bit about the project to build a new prison for women on the island of Montreal.

The first step in fighting new development projects is usually trying to find as much information about the project as possible. That research can involve many things; since the first contracts have already been awarded for the proposed new women’s prison in Ahuntsic-Cartierville, we wanted to get our hands on them. Long story short, that was pretty difficult. The province has put some annoying security mechanisms on the contracts that makes them somewhat easy to download anonymously but very tricky to open and share. However, we’ve seen them and they don’t contain much. We wanted to share all the relevant parts here for people looking to fight the new prison.

First, the government has not been honest about the real size of the new prison. The media reported that the new prison will have the capacity to warehouse 237 people. In fact, the contract calls for buildings that can be expanded to eventually hold 405 people. Yes, it is true that the timeline of this phase of the project stops at the point where there are 237 cells, but there are clear plans, though no proposed timeline, to expand it further in the future. These numbers are bigger than the original Maison Tanguay, but smaller than the capacity at Leclerc (which, let’s not forget, is an old federal prison with a sizeable capacity in a collapsing, leaky, drafty building.).

Second, the Elizabeth Fry Society of Quebec has their hands deep in this project. For those who don’t know, E. Fry Societies exist in most provinces. There is also a national organisation with the same name. They all seem to operate autonomously from each other, with the national organisation having the most radical politics. All of them have a mandate to help women who are experiencing or who might experience conflict with the legal system. The documents state that E. Fry Quebec is part of proposing a new model for the long term incarceration of women in Quebec, including ongoing consultation on this new prison. Clearly, the prison system has a not-for-profit wing, and E. Fry Québec is part of it. This is not necessarily a change from the status quo, but a clear example of collaboration.

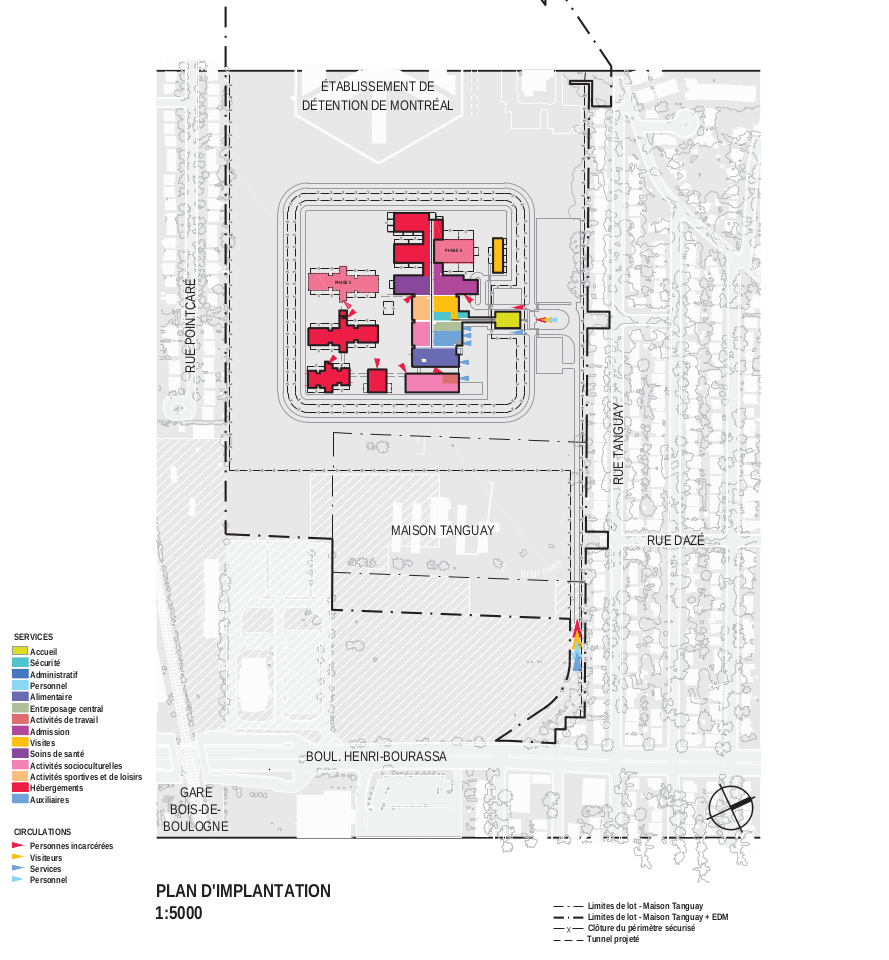

Third, the documents include five core things that need to be a part of the new prison. 1. The prison will be laid out in pavilions. 2. There will be different security levels adapted for different prison populations. 3. The exterior architecture will be aimed at deinstitutionalizing the buildings. 4. The interior appearance of the prison will preserve the dignity of the prisoners by offering an environment that is secure and calming. 5. The acoustics will promote the intelligibility of conversations.

What do they each mean? The first point likely means the new prison will be designed in pods. This can look different in different prisons, but, according to Escaping Tomorrow’s Cages, “pod prisons originate in a tough-on-crime approach from the 1990s when the system was preparing to lock up more people for longer. They are designed with two main considerations: cutting prisoners off from the community and saving money.”1 They also remind us that “the infrastructure matters more than the use” so we assume the trajectory of this new prison might resemble the “bungalows” that were built in some of the new regional federal women’s prisons after the closure of the Prison for Women in Kingston in the mid 90s – nicer at first, then eventually stripped down to solely their potential for surveillance and securitization.1

The second point, different security levels adapted for different carceral populations, is very clear. This trend in prison construction has been in the works for at least three decades now and is already present at many prisons in the country. It seems like the new Tanguay will have a segregation unit and a maximum security wing. Due to centuries of colonialism and white supremacy, Indigenous women are incarcerated in Canada and Quebec at high rates. There are especially high rates of Indigenous women in segregation and maximum security units.2 No surprise the government wants both segregation units and a maximum security wing at this new prison.

The third requirement for this project is also part of a trend in prison construction in the last decade. By making the prison look friendly and welcoming, the government hopes that everyone will be convinced that it’s not a place where poor people and people of colour are locked up and punished. The same goes for the interior environment, which must be both calm and soothing. Basically, you need curtains on the windows and pretty pictures on the walls of the maximum security unit. Last but not least, acoustics that allow conversations to take place. This says more about the acoustics of most prisons than anything else. Prisons are very noisy. They want to try and make this one a little quieter. Someone applaud them. It was also pointed out that maybe it’s a safety issue. If conversations are more audible, they’re more recordable. It’s not clear what this is about, but it’s a not great either way.

We’ll take an aside here to preach to the choir. Prison reform is a dead end. Ann Hansen said it well in Taking the Rap; “New prisons come wrapped in progressive packaging, decorated with pictures of rehabilitation and programming, but once they are opened, out comes a shiny new prison filled with all kinds of technological gadgets designed for enhanced surveillance and security that cost so much, the prison regime claims it can no longer afford all the progressive programming promised on the packaging.”3

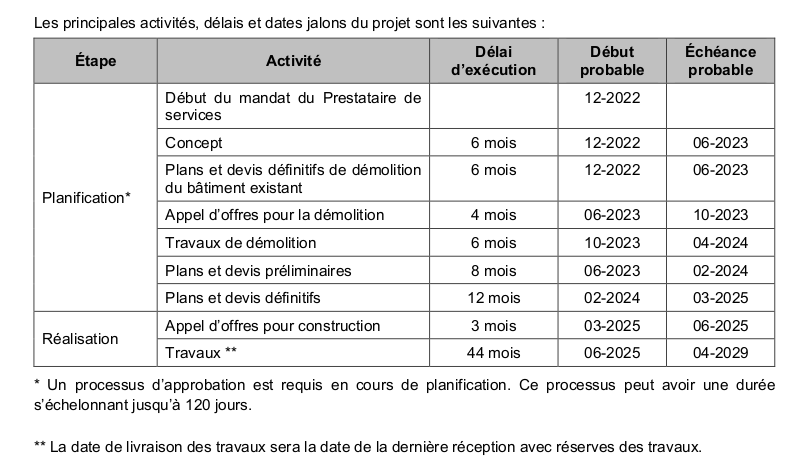

What else is in the documents? There is a timeline for the project. Its all planning and demolition work into 2024. Call for tenders for construction starting in May 2025. Construction slated to happen from July 2025 to April 2029. Here’s a screenshot of it.

The fifth and final thing in the documents is a list of names and responsibilities of people involved in the project. If you’re looking for some specific people to hold responsible for this project, here’s a few to start with: Project Head (project manager, SQI) is Amélie Viau. Minister’s Representative is Bruno Gosselin. Contract Manager (Head of expertise, SQI) is Nathalie Duchesneau. CGPI (integrated practice management consultant) who participates in the first steering committee and remains available to support the project team throughout the project’s mandate is Sébastien Parent. BIM Representative is Zakia Kemmar.

We’ll leave the last words to Ann Hansen; “Prison reforms are doomed to eventual failure, but that does not mean that we cannot use the fight for reform within a revolutionary context as a means of raising awareness. Real people are suffering in prisons now. If any one of us were stuck in solitary confinement for years at a time, would we want to wait for the revolution before anyone tried to help us? The answer lies in the murky grey zone between struggling for reform and struggling for revolutionary change. These struggles are a false dichotomy in which the murky grey zone can be bridged. As long as concrete campaigns for reform are framed within a revolutionary context and are guided by revolutionary principles, then they can play a role in the campaign to abolish both capitalism and its social control mechanism, prison.”4

1. From Ann Hansen’s book Taking the Rap: “Between my two short stints in GVI [Grand Valley Institution, a federal women’s prison in southern Ontario] during 2006 and then again in 2012, i witnessed the devolution of GVI from a prison compound where women cooked and lived collectively in bungalows perched neatly in grassy, tree-lined yards, where vegetables were grown in kitchen gardens and the women moved freely from eight in the morning until ten at night throughout the compound… to a multi-security prison complex with few jobs or programming and with double-bunking everywhere, including maximum-security units and segregation. This devolution unfolded in all six regional federal prisons for women during the fifteen years after P4W closed in 2000. this feat is surpassed only by the fact that the entire federal prisoner population for women actually in prison had increased by 40 percent, to 550 women, in the ten years after the closure of P4W. This in a country where the crime rates have been on a steady decline over the past two decades.” p. 336-7

2. Quebec doesn’t keep stats about this specific thing as far as we can tell, but as of 2019-2020, Inuit and First Nations women made up 9.6% of the women’s prison population in Quebec. “Les Inuites, les femmes sans diplôme, les célibataires, les femmes vivant seules, présentent des taux, d’incarcération nettement, plus élevés.” A recent report showed that 96% of the women being held in the new SIU seg units in the federal system were Indigenous women.

3. p. 339, Taking the Rap

4. p. 343, Taking the Rap