From It’s Going Down

Intro from the IGD Bloc Party column:

In an effort to broaden our coverage of prisons across the borders to both the North and South of us, we’ve brought in some comrades from so-called Canada to share a history of the establishment of the Canadian prison system, as well as a history of resistance in Ontario and Quebec.

While we know there is always resistance that we will never hear about outside the prison walls, these folks have done their best to contextualize what resistance has looked like across decades. We’re excited to share this history!

We’ll be back next week with a follow up interview with these comrades that catches us up on current prisoner resistance and support efforts in Quebec and Ontario. Next week we will also include both the article and interview in zine format for you to add to your distro tables. Now for all that history from the bloc…

This piece is written by a couple people who have been engaged in anti-prison, prisoner justice, and prisoner support organizing for almost ten years. We are not academics, nor are we ex-prisoners. However, much of the information compiled within this text comes to us from people who have done a lot of time and a lot of research and we are grateful to them for sharing their stories and their research. We consider this to be a working document, and welcome your feedback at: canprisonzine@riseup.net

This text started off as a presentation for Americans on the Canadian prison movement. It also covers our relationship to the prison movement from our perspectives in Kingston, Ontario and Montreal, Quebec.

Most of this article focuses on the situation in federally run prisons. In Canada, people are sent to federal prison if they receive a sentence of 2 years plus a day, and they are managed by the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC). We generally zoom in on the situation in federal prisons for men in Ontario and Quebec even though there is much history to be told regarding federal prisons and provincial jails elsewhere in Canada. Also, we are both white anarchists who have, for the most part, organized and heard stories from cis men.

We want to say up front that the history in this article is not comprehensive, and leaps forward decades at a time – otherwise this would have turned into a book. We focus most of our energies on the 1970s because the stories we have heard over the years from people on the inside tend to focus on those years as the beginning of an era that is perhaps now coming to a close.

From what we have heard, norms set for prisoner solidarity and expectations vis a vis the administration in the 1970s tended to carry on for the decades afterwards. Though many things have changed since then, focusing on the 1970s seemed like a good way to center the stories we wanted to tell.

PENITENTIARIES, SLAVERY AND COLONIAL EXPANSION

A good way to reveal the underlying intent and function of a repressive institution like the Canadian prison system is to dig into its history. A lot of solid work has come out of the U.S. in the last few decades that effectively describes the U.S. prison-industrial complex as the ongoing legacy of slavery. While Canada did indeed have slavery (contrary to official myth) and slavery in Canada is part of the history of prisons in this country, it’s also necessary to situate the emergence of the Canadian penitentiary system as part of the project of British colonial expansion.

Canada likes to present itself as, historically, a safe haven for Black people escaping slavery in the United States. However, the institution of slavery existed here until 1833 and was followed by an era of Jim Crow like segregation. There have been centuries of overrepresentation of Black people in state run institutions of confinement. White supremacy, as an institution in Canada, was shaped by the enslavement of Black people. In the almost two centuries since the abolition of slavery, Black people have been consistently criminalized, policed, and harmed by the state and civil society. Although making the easy connection between a prison that used to literally be a plantation is harder to do north of the American border, there is no doubt that slavery and criminalization of Black people has shaped the institution of prison in Canada.

Following Canadian Confederation in 1867, colonization and settlement continued to rapidly spread west of Ontario. Along with the establishment of the North-West Mounted Police and the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, penitentiaries were constructed to extend Canadian law and assert colonial jurisdiction in the west.

Stony Mountain Penitentiary provides a telling example. Following the Red River Rebellion inspired by Métis leader Louis Riel, the Province of Manitoba was imposed and Stony Mountain Institution was constructed in Winnipeg. The first warden at Stony was a member of the military unit stationed nearby who had been dispatched to put down the rebellion. When a second uprising broke out in 1885, known as the North-West Rebellion, the partially-built Canadian Pacific Railway carried military troops and North-West Mounted Police to outmaneuver the Métis, Cree, and Assiniboine rebels. After a short show-trial Louis Riel was convicted of high treason and hanged, on orders of Canada’s first Prime Minister, John A. Macdonald. The other rebel Chiefs were incarcerated at Stony Mountain, where their health deteriorated rapidly. Shortly after being released, they died.

The history of the prison system is also tied up in the residential school system. The residential school system were boarding schools that the government forced indigenous children to attend. The similarities between prisons, asylums, poorhouses, workhouses, Houses of Refuge, reformatories, reform schools and residential schools is no accident. The residential schools set up in the 1860s and 70s were modeled on the ‘industrial schools’ and ‘reformatories’ organized by Upper and Lower Canada, which were themselves hybrids of prison and school for younger offenders. Even the ‘curriculum’ – forced labor, with a vocational bent, remedial schooling, quasi-military discipline – was similar. The chief difference is racial – ‘saving’ a child in a residential school meant trying to abolish all aspects of their previous identity and material existence, and the entire ‘rehabilitation’ apparatus was turned to “kill the Indian, save the child.”

1930s-1960s

There has always been resistance to confinement, but starting in the 1930s, prisoners in Canada began to organize as prisoners. The riots at Kingston, St. Vincent De Paul and Dorchester in 1932-33, followed by demonstrations during the rest of the decade at those and other prisons, set the pattern in that they were the first explicitly political disturbances organized by prisoners as prisoners. Previous riots and strikes although organized around work conditions or food or removing a particular guard, rarely questioned the entire basis of the prison, or demanded outside intervention.

This era also ushered in a cycle we can clearly identify in Canadian Penitentiaries. The cycle starts with a wave of resistance inside that escalates to riots and strikes. This creates a political scandal. The government responds by appointing a body (Royal Commission or Inquiry) to investigate and make recommendations. If the same government is in power, some recommendations are implemented, especially the more regressive ones like more control, more prisoner labor, more segregation. Sometimes the new reforms and/or new facilities are so much worse, that this triggers another cycle.

Here’s an example of the cycle in action. There was a major riot at Kingston Penitentiary in 1954 where the building was set on fire. In the aftermath of the riot, the Fauteux Commission was convened to respond to a perceived crisis, which recommended work and social programs be created to modify “behaviors, attitudes and habits”. The commission set in place a new army of specialists inside prisons (social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, criminologists) and also created the Parole Board to “create better relationships between guards and prisoners”.

At the same time these reforms were implemented, prison construction boomed. The government built 25 new prisons by 1970. In this time period, there was a trend towards a widening of the security classification system in prisons. The creation of the first ultra-max and the first halfway house were evidence of this trend. Two of the new max prisons – Millhaven in Ontario and Archambault in Quebec – were identically designed and came to symbolize the violent unrest throughout the 70s, which would lay the basis for the contemporary prison movement in Canada.

Another important marker of this time period was the unionization of the guards in the federal penitentiaries. This unionization in 1968 gave the guards a surge of power that contributed to the escalating tension through the 1970s as they ensured the government could not implement reforms demanded by the prisoners. If any guard was seen as being too soft on prisoners, the dominant hardcore guards would brand them a ‘con-lover’ and dole out “beatings at the local Legion Hall, slashed tires, rocks thrown through their living-room windows, and threatening phone calls.” The guards’ union continues to be a reactionary organization that uses prisoners as pawns, and is very politically active in opposing the campaign against solitary confinement, for example.

1970s

The 1970s were a decade marked by violent unrest and repression inside Canadian pens and continue to act as a reference point for the contemporary prison movement. In Ontario, Millhaven Institution was constructed, where authorities planned to transfer all the prisoners from Kingston Penitentiary. Rumours were circulating amongst prisoners that Millhaven would be an environment of complete control, that it would be impossible to take collective action there, and so prisoners started planning a final stand at Kingston Pen. As tensions increased, the administration cracked down on communication with the outside world and on social activities inside, and abolished prisoners organizations, sending anyone they suspected of planning unrest to segregation. In April 1971, Kingston Pen saw the largest prisoner uprising in its 178 year history. Six guards were taken hostage and prisoners took control of the building, destroying most of it. The hated brass bell, which regulated the daily routine of prison life and rang 178 times each day, was smashed to bits.

The standoff lasted 4 days. Prisoners hid their hostages, made weapons and barricaded entrances, which deterred an immediate raid. Hundreds of soldiers were deployed from the nearby base. General assemblies were held inside to make key decisions. After anonymous guards fed vicious rumours to the media about sexual assaults occurring inside, the prisoners had journalists tour the prison they controlled. A local support group camped out among the cops, media, guards and army with a large banner that said “We Support The Prisoners.” Prisoners inside saw it and responded with their own banners: “Thank You For Your Support,” “Under New Management,” and “The Devil Made Me Do It.” Some prisoners formulated demands, while others were determined to die in battle. The prisoners demand for a Citizens Committee to mediate the crisis was granted.

On the 4th day, negotiations were deadlocked over the question of amnesty, the government was signaling an imminent assault, and there was a power struggle among the sleep-deprived, hungry prisoners, A faction took control that believed it necessary to show the army they were capable of killing hostages, and organized a brutal display of violence against prisoners from the protective custody unit, who were considered by the general population to be ‘undesirables’ and assumed to be sexual predators and snitches (although this is not always the case). Two prisoners were killed in the beatings, which according to ex-prisoner Roger Carron’s account demoralized the rebels, and led to their negotiated surrender shortly thereafter.

Most of the rioters were transferred to Millhaven and locked up in segregation, partly as punishment and partly because Millhaven was still under construction. The system took retribution:

[Millhaven] early history was marked by the use of clubs, shackles, tear gas and dogs, often in combination. Dogs were let loose on prisoners in the yard and in their cells. Gas was used to punish prisoners frequently —– in March 1973, as often as three or four times a week. Prisoners who were first shackled, sometimes hands and feet together, were then beaten with clubs, made to crawl on the floor, and finally gassed. – 1976 Commons Justice Committee

Earlier hostage takings, namely one that happened in January 1971 in Kingston Penitentiary, involved racialized prisoners demanding better treatment for non-white prisoners. The 70s also marked an era when racialized prisoners got more organized, a prominent example being spread of the Native Brotherhood and Sisterhood that fought for access to cultural and spiritual programming for indigenous prisoners and exists to this day. Using hunger strikes, connections with indigenous communities on the outside, and lawsuits, the Brotherhood and Sisterhood were a force to be reckoned with and continue to organize to this day.

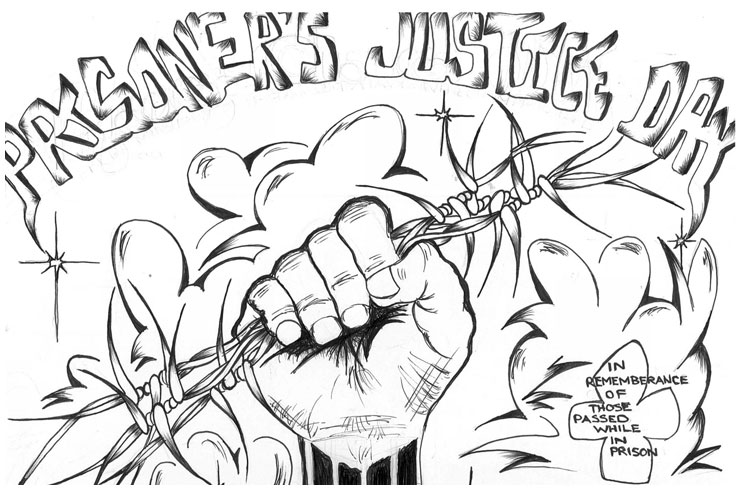

On August 10, 1974 Eddie Nalon bled to death in Millhaven’s segregation unit after cutting himself with a razorblade, after a lengthy dispute with the institution over a transfer. The investigation into his death revealed that the guards had disconnected the emergency signaling system. On the first anniversary of his death, prisoners refused work and food to mark Nalon’s death and to show solidarity with an ongoing strike at British Columbia Penitentiary, a strike that would spread to Collins Bay and Joyceville Institution in Ontario. Involuntary transfers resulting from protests and strikes inside would then help spread word of the struggle across the country. After the death of prison organizer Robert Landers in 1976 in Millhaven segregation, August 10 would come to be known as Prisoners Justice Day or PJD, and continues to be a major day of mourning and protest at jails and prisons across Canada.

THE 1970s IN QUEBEC

As an introduction to writing about this period of time in prisons in Quebec, it is necessary to give some Quebec specific context. In the 1960s, the popular movement for Quebec separatism was heating up. In 1970, the Front de Liberation de Quebec (FLQ), an armed national liberation group, carried out two kidnappings, one of which ended in the assassination of Pierre LaPorte. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (the current Prime Minister’s father) passed the War Measures Act and sent the army into Quebec, which resulted in the arrest of around 500 people in Montreal and the surrounding areas. The culmination of this struggle was the election of the Parti Quebecois to power in the provincial government in 1976. Some folks affiliated with the FLQ ended up in the federal jails in Quebec while some sought asylum in Cuba. This atmosphere of struggle created a context for the struggle inside prisons in Quebec as people involved in movements on the outside ended up in prison and movements on the inside heated up in their own right.

In 1976, a massive work strike started in the federal prison called Archambault in Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, Quebec. 350 prisoners began a work strike to force an improvement in their living conditions and to express sympathy for a strike that was already underway at another federal prison called St. Vincent de Paul in Laval, Quebec. The Archambault strikers’ central demand was for physical contact with visitors.

An outside group composed mostly of wives, families, and friends of the prisoners organized two demonstrations during the 1976 strike; one in front of Archambault and one in front of St. Vincent de Paul. Prisoners at a provincial prison on the island of Montreal began a sympathy hunger strike. Two former St. Vincent de Paul prisoners accidentally blew themselves up with a bomb they were trying to place in a bus station near the prison as a gesture of support for the strike. The Archambault strike ended after about five months when the prison administration formally recognized the prisoners committee. Permission was also given for frequent visits to the institution by a citizens committee. Prison officials also announced that physical contact during visits would begin in spring 1977.

In 1978, Archambault warden Michel Roy was murdered. Paul Rose, an imprisoned member of the FLQ, who was then a member of the prisoners committee at Archambault, told a Montreal newspaper that conflict at the prison had become serious. He and other members of the prisoners committee had been transferred to the segregation block at a different federal prison in Quebec as a result of their advocacy on behalf of other prisoners at Archambault. The warden had denied that conditions were deteriorating in the prison and refused to relate to the prisoners committee as a negotiating body of any kind. Three former prisoners (one of whom had escaped in 1977 and was on the run) were charged with the murder of warden Michel Roy and during their trial, one of them said that they did it in order to draw attention to the poor conditions at Archambault.

The 1970s ultimately ushered in the abolition of corporal punishment and capital punishment (which was replaced with the life sentence). The Office of the Correctional Investigator created to ‘address prisoner concerns’. Prisoners Committees, which were by and large organizations (both aboveground and underground) that were formed by grassroots prisoners to organize resistance and communicate with the outside world, were recognized and regulated in federal prisons in 1978. Importantly, the act of recognizing the Committees and entrenching their role in policy was part of a CSC strategy to pacify resistance. Inmate Committee membership is subject to approval by the administration, and anyone who goes ‘too far’ can be removed. Committee members are under tremendous pressure from the administration to manage unrest by channeling it into ‘constructive’ channels such as CSC controlled grievance processes. That said, the role of Inmate Committees in mobilizing or pacifying resistance depends on the specific institutional context.

These reforms also extended the logic of security classification, which provides incentives (privileges) for ‘good behaviour’ while incarcerated, such as the ability to work outside the institution, kitchenettes for cooking personal meals, contact visits, etc. Of course, these privileges are more effective instruments of control with a corresponding expansion of punitive brutality and dehumanization for ‘badly behaved’ prisoners with a higher security classification. So Millhaven-style max prisons were constructed at the same time as minimum security camps throughout the 1970s.

1980s AND 1990s

The turmoil inside Canadian prisons in the 1970s led to some tweaks to the system, but the struggle continued through the 80s and 90s with many of the same reference points. We’ll briefly touch on three issues of focus from that period: control units, harm reduction, and the scandal at the Prison For Women.

In the 80s, we can see prisoners and their supporters warning against Marionization, which was language used to describe the generalization of the control unit prison model in Marion, Illinois. Marion was built in 1963 to replace Alcatraz, and is most famous for the brutal behaviour modification and drug experiments done on prisoners there. It served as the basis for ADX Florence in Colorado and Pelican Bay in California.

In Canada, there were ‘Special Handling Units’ built on the grounds of maximum security prisons in each region in the late 1970s. They were, along with Life 25 sentencing, understood as part of the tradeoff for the abolition of the death penalty in 1976. Life 25 is short for a sentence of 25 years to life where one becomes eligible for parole after 25 years, but will be on parole until their death. Throughout the 80s CSC kept expanding its policy definition of ‘dangerousness’ and more prisoners ended up in the SHU. In 1984, the Special Handling Unit prison was built in Quebec to replace the individual units across Canada. Life in the SuperMax SHU is especially violent, miserable, and under complete video surveillance. A transfer to the SHU is a common punishment for escape attempts, violence directed at guards, or if a prisoner is classified as ‘radicalized.’

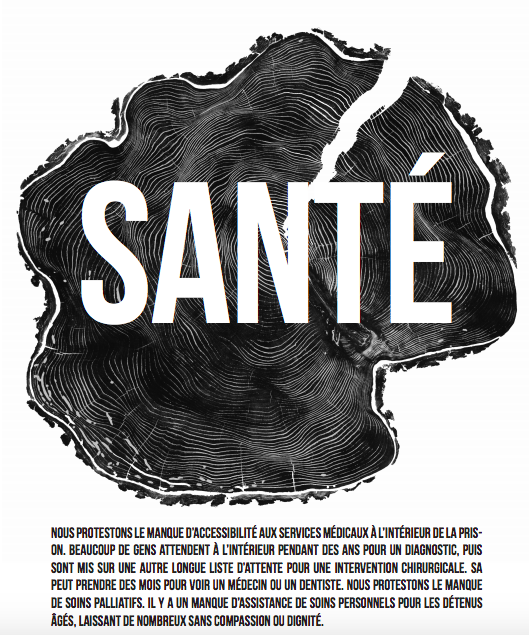

Another major focus in the 1980s and 1990s was harm reduction amidst skyrocketing rates of HIV, Hepatitis C and tuberculosis within Canadian prisons, rates that were up to 70 times higher than outside prison. Prisoners agitated for educational resources, safe tattoo programs and needle exchanges. Out of this context, we see the emergence of organizations such as PASAN that continue to do important educational and advocacy work inside and out.

While it’s true that what happens behind prison walls is largely invisible to the public, it’s doubly true in prisons designated for women. In Canada, women were incarcerated in a special unit of Kingston Penitentiary until 1935, when the Prison For Women (P4W) was built across the street. In April 1994, following a fight, six women were put into segregation. 2 days later in the segregation unit, there was a suicide attempt, a slashing and a brief hostage-taking. After guards publicly demonstrated for the transfer of the women involved in these incidents, the Warden ordered in the all-male Emergency Response Team to do a cell extraction and strip search of 8 women in segregation, which was videotaped as per the procedure. The women were then shipped to a special unit in Kingston Penitentiary. A year later, following an investigation, the video footage of the raid and strip searches were aired on the investigative CBC program Fifth Estate, generating public outrage and leading to a federal inquiry and the rapid closure of the Prison For Women, replaced by Grand Valley Institution in Kitchener, Ontario. Women’s prisons continue to have the highest suicide rates in the country, and the death of Ashley Smith in segregation in 2007 has reignited the cycle of incident, public outrage, government inquiry and recommended half-measures.

CURRENT CONTEXT

From 2007-2012, there was another prison expansion boom in Canada. In the name of “tough on crime” politics, then Prime Minister Stephen Harper built or expanded 30+ prisons across the country. Legislation contributed to the trend towards more people doing more time in Canada. Fewer people were getting parole, parole restrictions were getting harder to follow, and more people were being thrown back in prison on parole violations like “lack of transparency” (its just as vague as you’re thinking).

In 2013, Harper cut the pay for federal prisoners by “raising the price of room and board” even though prisoners hadn’t had a pay raise since the 1980s and there was already a provision for room and board set in the original pay rate. The pay cut was followed by a wave of work strikes across federal prisons in Canada. The work strikes ended when things moved into the court system with a lawsuit on behalf of the striking prisoners. In January 2018, the Federal Court ruled against prisoners, which will likely lead to more unrest. Federal prisoners now make about $3 a day if they are at the top of the pay grade in the institutions (a pay grade which is getting harder to access).

In general, it seems that things are getting harder inside. Prisoners report less solidarity among prisoners and more psychological pressure to conform to Correctional Services set behavioral norms just to get furloughs, parole or trailer visits with family.

The things that prisoners fought for in the 1970s are slowly disappearing. Access to education and trades are drying up, families are being put through more security measures before being allowed inside, and most programming is run by Correctional Services staff, not independent specialists. A prisoner being denied parole by the Parole Board of Canada in the Harper era was told that his decade plus years inside weren’t so bad. “At least you’re not in prison in the US”, they told him.

After the election of Justin Trudeau, some federal prisoners were hopeful that things would change. They wrote an open letter to Trudeau demanding changes to the federal prison system. They got a form letter back from the Justice Minister thanking them for their letter. None of the changes they called for have been implemented, although it does seem like more people are being granted parole than during the Harper era.

RACE AND CANADIAN PRISONS

As we said in our history section, white supremacy, anti-Blackness, and colonialism are fully manifested and cemented in the prison system. Indigenous adults make up nearly 24% of admissions to provincial prisons while representing 3% of the Canadian adult population (provincial prisons house both people sentenced to 2 years less a day and people awaiting trial). The figure is 20% for federal sentenced custody. Indigenous people in Canada are more likely to receive prison sentences (as opposed to house arrest or community sentencing alternatives) than white people. Indigenous women are especially targeted by the prison system. Currently, Indigenous women make up 36% of all people sentenced to provincial/territorial prison sentences.

To put these trends into a time period, between March 2003 and March 2013, the number of people incarcerated in Canada increased by 2,100 people or 16.5%. The number of Indigenous people in prison increased by 46.4%. The number of Indigenous women who received federal prison sentences increased by 80%. The number of people from visible minority groups who were imprisoned increased by 75%. The number of Black people in prison increased by 90%. Over that same ten year period, the number of white people in prison decreased by 3%. All these statistics are from the Annual Report from the Office of the Correctional Investigator from 2013. The Correctional Investigator is the official Ombudsman for prisoners in the federal prison system.

In that same report from 2013, there is a section on the situation facing Black people who are incarcerated. Black people in prison in Canada make up 9.5% of the total prison population as opposed to 2.9% of the population outside prison. Black prisoners are more likely to be put in administrative segregation, more likely to be classified as high security, less likely to be assigned work in prison, and less likely to be able to access culturally relevant (and honestly, non-racist) programming. There are stories in that report about folks attempting to do a GED inside being forced to read racist books as part of the program. There are very few programs that connect Black prisoners with Black community members on the outside – which is super important in a federal context because often, you have to demonstrate that you have community connections to the Parole Board if you want to be released before the expiration date of your sentence.

To add to this snapshot of white supremacy, anti-blackness, and colonialism as related to the Canadian prison system, we’ll share a story. We heard a story of someone who had been in prison since he was a teenager. He has a life sentence. When he was in the process of applying for parole, he (like everyone else) was mandated to do a “psychological assessment”. At the same time, he was applying for recognition of membership in an Indigenous nation. He got his results for the psychological assessment before the government formally recognized his membership. Initially the assessment said that his likelihood to re-offend was 20%. However, once his status was recognized and that status (he is Métis) was included in the assessment, his likelihood to re-offend shot up to 50%. Nothing else had changed, they didn’t redo the assessment. It was simply that his racial status on the assessment changed.

This is just a small picture of the realities of white supremacy, anti-blackness, and colonialism in Canada as they relate to the prison system. There are tons more stories not shared here. Please be sure to check out the further reading suggestions at the end of this article.

ANARCHISTS AND ABOLITIONISTS

In Canada, there is a distinct prison abolition movement that both overlaps with and diverges from anarchists struggling against prisons. There are many committed, sincere and solid people who primarily identify as prison abolitionists. Historically, prison abolitionists have supported so-called social prisoners, while many anarchists have been involved in political prisoner/prisoner of war support. However, anarchists may also identify as abolitionists, recognizing that all imprisonment is political. In recent years, especially with the influence of insurrectionary anarchism on anarchist milieus in Canada, anarchists have made steps towards supporting anyone resisting in prison.

Abolitionists, on the whole, tend to be more interested in direct support and reform-oriented campaigns and legal battles, and are more supportive of ‘non-violent’ resistance. In some cases, they may have more resources and be in a better public position to support prisoners than the anarchist movement. Anarchists have sometimes found themselves mostly supporting prisoners south of the border or elsewhere in the world, given the framework of political prisoner/prisoner of war/anarchist prisoner support and the dearth of prisoners who fit this framework in the Canadian prison system.

It is possible that political differences between those who see a future where there are no longer prisons, but the state is intact, and those who want to see an end to the state and its prisons will be exacerbated in the Trudeau years with a return to hegemonic liberalism in federal politics. A stark example of this is Kim Pate, a self-described abolitionist who has spent her life advocating for women in prison as Executive Director of the Elizabeth Fry Society. In 2016, Pate was appointed to the Senate, the Upper House of Canadian Parliament, where she has gone pretty quiet about abolition, talking instead about ‘decarceration.’ This raises the question of whether prison abolitionism as an ideology implies meaningful opposition to the state itself.

A major influence on both anarchist and abolitionist critiques of prison in Canada is the legacy of Clare Culhane. Clare cut her teeth at union organizing in the Montreal garment industry before moving to British Columbia where she got involved with the nascent Prisoners Union Committee during the tumultuous 1970s. During a riot at BC Pen in 1976, prisoners requested Clare be part of a civilian group that would help negotiate an end to the standoff. She agreed and was instrumental to negotiating a bloodless resolution, and then immediately banned by authorities from going into any more prisons. Clare became an active writer and speaker on the topic of prison abolition, got involved with organizing public events for Prisoners Justice Day, and was active in the cause until her death in 1996.

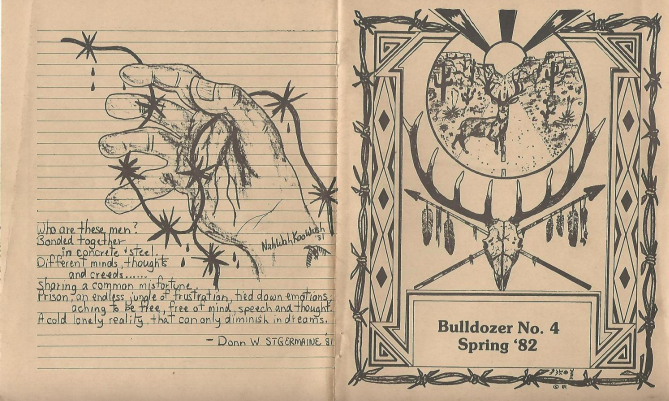

Bulldozer was an anti-prison anarchist project founded in 1980 out of the Toronto counterculture scene. They also organized PJD events and published a newsletter of prison writing called “Bulldozer: The Only Vehicle For Prison Reform.” They were raided and charged with sedition for their open support for Direct Action, an anarchist urban guerilla group active across Canada in the 1980s. The newsletter project was revived in the 1990s as a collaboration between Bulldozer member Jim Campbell and anarchist political prisoner Bill Dunne. This project would evolve into the Prison News Service, which was published until 1996.

Across Ontario, Anarchist Black Cross projects were revived in Ontario throughout the 2000s, with chapters springing up in Toronto, Guelph, and Peterborough. This would prove to be an important support network for anarchists and others who faced repression for their organizing against the G20 Summit in Toronto in 2010. There has also been a lot of activity in solidarity with migrants resisting indefinite detention via the End Immigration Detention Network.

In Kingston, End the Prison Industrial Complex (EPIC) was formed in 2009 to intervene in the local Prison Farms movement with an abolitionist perspective. After the farms were closed, EPIC shifted gears and built a campaign against prison construction primarily targeting private contractors which ended after an attempt to blockade Collins Bay prison on PJD in 2012. Since 2012, EPIC has moved to espousing more explicit anarchist politics, publishing an irregular prison newsletter and acting in solidarity with the struggles of local prisoners, such as the federal prison strike against pay cuts in 2013. CFRC Prison Radio provides an important link between the 8 prisons in the broadcast range and the Kingston community for coordinating support and solidarity.

In Ottawa, there is a network of abolitionists based in the community and the University of Ottawa involved in a variety of support work and campaigns, including the #NOPE/No On Prison Expansion project led by the Criminalization and Punishment Education Project.

In Quebec, a lot of 1970s era prisoner advocacy was organized by the Lique des Droits’ Prisoners Committee, which supported the prisoners on strike in 1976 in Archambault. The Prisoners Committee was forced to end formal ties with the Ligue des Droits after Centraide (the United Way) threatened to pull the Ligue’s funding if they didn’t distance themselves from the Prisoners Committee. In 1984, the group became their own non-profit. They have played a big role in prisoner advocacy from the outside over the years.

The Coalition Opposé à la Brutalité Policière has also always been connected to prisoners justice support in Montreal. They were very involved in organizing around Prisoners Justice Day in Montreal on the outside in the 1990s.

Over the years in Montreal, people doing prisoner advocacy and support and anti-prison organizing have been involved in programs on the inside, organizing noise demonstrations outside of the prisons, supporting people arrested at annual demonstrations, and publicizing resistance that happens in the provincial and federal prisons in and around the city.

Montreal is currently home to a Prison Radio Show, the Prisoner Correspondence Project (a queer pen-pal program for prisoners), a Books to Prisoners chapter, various legal defense funds connected to student unions and the CLAC, and an annual New Years Eve noise demonstration outside of the prisons in Laval, a nearby suburb. Toute Detention est Politique (Every Detention is Political) has organized conferences and demonstrations, written analysis of the prison system, and publicized prisoner resistance in the provincial jail for women. The Certain Days Political Prisoners Calendar project has some of its base in Montreal. PASC organizes popular education about prison and supports political prisoners in Colombia. Solidarity across Borders is a local migrant justice organization that is organizing against the construction of a new immigrant detention center slated to be built in the Montreal area in the coming years. Anarchists and other radical organizers in the city have also coordinated ad-hoc support for hunger strikers in prisons in California and elsewhere in the US, as well as support for prisoners resisting in Quebec and the rest of Canada.

CONCLUSION

So ends our snapshot of Canadian prison history and current struggles in Kingston and Montreal. Obviously there are things we didn’t cover. It is exciting to share this with people in the US and across Canada, but it also feels weighty or even a little scary given how few histories like this have been written. We hope that anyone who has personal and/or research experience with these histories will engage with us. We’d love to be challenged on some of the conclusions we have drawn throughout this piece! Contact us at: canprisonhistoryzine@riseup.net

FURTHER READING

Books

The Hanging of Angelique by Afua Cooper

Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to Present by Robyn Maynard

Bingo! by Roger Caron

Prisons in Canada by Luc Gosselin

Only A Beginning: An Anarchist Anthology by Allan Antliff

Writing As Resistance: The Journal of Prisoners on Prisons Anthology (1988-2002)

Clearing The Plains by James Daschuk

Articles & Websites

Canada’s Long History of Anti-Black Racism

âpihtawikosisân’s Online Learning Resources

Tracking the Politics of Crime and Punishment in Canada

Native Spirituality in Prisons

Conversations with Dino Butler

The Penal Press – A History of Prison From Within

Journal of Prisoners on Prisons

Discipline and Punish: Prison ‘rehabilitation’: another form of punishment and control

Canada Has a Black Incarceration Problem