From the Graphic History Collective

Poster by Adèle Clapperton-Richard

Introduction by Andrée Lévesque

The 1930s are remembered as a time of widespread hardship when the world was rocked by capitalism’s economic crisis. Montréal, with its large working-class population, was particularly hard hit by mass unemployment and a falling standard of living. The dismal conditions for working people prompted a renewal of activities by protest movements, largely led by the Communist Party of Canada. Labour strikes, unemployed demonstrations, and marches to protest against welfare cuts were just the most visible manifestations of popular unrest.

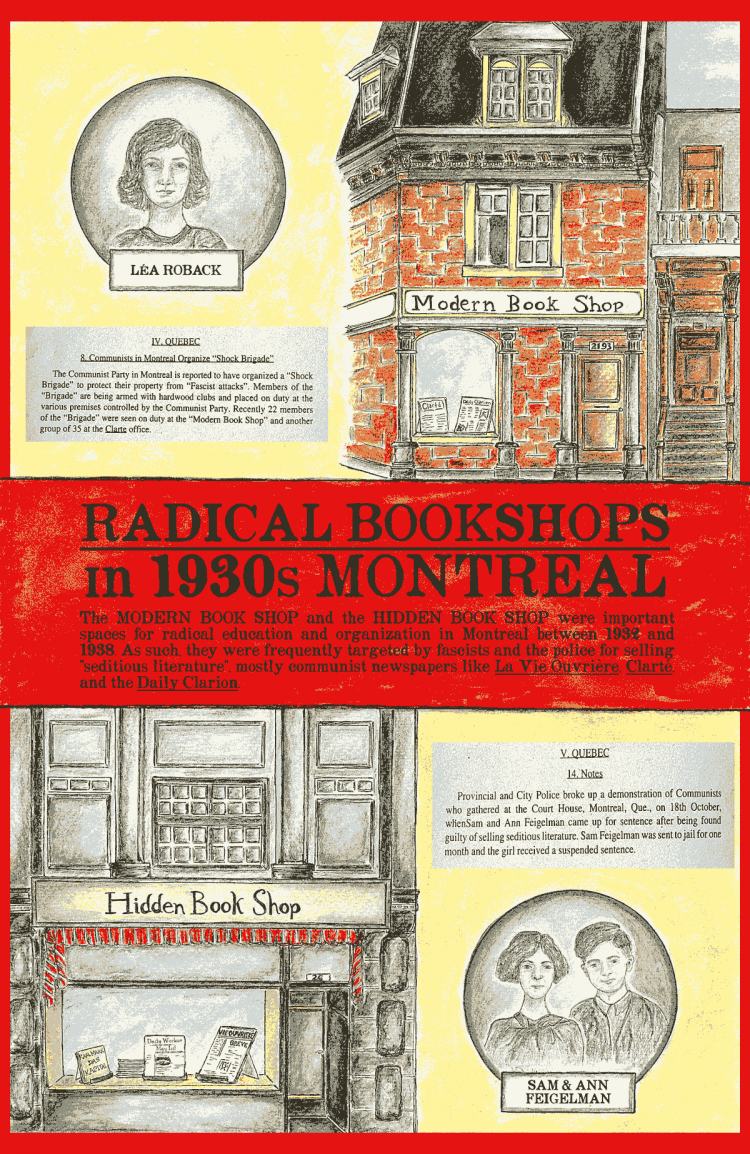

Left bookshops played an important role in educating and mobilizing people and developing and sustaining networks. Books have always been essential tools of conscientious-raising. For centuries, authorities have attempted to control the written word that was considered a threat to the social order. In the 1930s, there were two left bookshops in Montréal closely linked to the Communist Party. In 1933–1934, the Hidden Book Shop on Saint Catherine Street, was managed by Ann, 20 years old, and her brother Sam (Sol) Feigelman. They could not sell communist books and newspapers freely because Section 98 of the Criminal Code, which the federal government created in 1919 to crack down on labour and left activists following the Winnipeg General Strike, made it illegal to “sell, speak, write or publish” anything related to an “unlawful association.” The definition of “unlawful association” was vague, referring to groups that advocated the use of force to bring about political change, which included many left and labour organizations. In June 1933, the Hidden Book Shop was raided, and Ann and Sam were charged and found guilty of selling seditious literature literature that encouraged people to revolt against the state. Amongst the seized literature was Vie ouvrière, a communist monthly published by Paul Moisan, Évariste Dubé, and other communist militants.

When the Modern Book Shop opened in Montréal a few years later, the legal situation concerning seditious literature had changed, but it was no less repressive. Section 98 had been repealed, but in Québec, the newly-elected Union Nationale government, headed by Premier Maurice Duplessis, together with the Catholic Church had launched a vast anti-communist campaign in October 1936. Bookshops were among the first places to be targeted in crackdowns on published material. A young activist by the name of Léa Roback, along with Jack Gold and future member of the legislature Fred Rose, set up the Modern Book Shop, located on Bleury Street near Dorchester. The bookshop sold progressive novels, journals, pamphlets, and newspapers, such as The Daily Clarion from Toronto, and Clarté, the Montréal weekly started in 1936 by Stanley Bréhaut Ryerson and others.

More than once Roback had to confront the police, who kept a close eye on the “subversive” books and newspapers. The forces of law and order may have spared the Modern Book Shop, but they did not do much to prevent acts of vandalism and broken windows against the shop either. On 27 October, The Montreal Gazette reported the content of a threatening letter received at the bookshop: “Last Warning. We give you three days to close everything or else we put dynamite around the Modern Book Shop. The police are with us and you know it. We will be there this week. We are and will remain Fascists.” A few months later, in March 1937, the Québec legislature unanimously passed the so-called Padlock Law that allowed the police to close down any premise used to disseminate “Bolshevik” propaganda. The law applied to bookshops, meeting halls, even private houses, making it increasingly difficult to organize meetings and sell left literature.

Left bookshops are more than just places where reading material is sold. They play an important social function: new publications are launched, meetings are held, and leftists engage with other leftists. Léa Roback met noted communist doctor Norman Bethune for the first time at a left bookshop. Singer Paul Robeson said that wherever he was touring, he would always stop at a left bookshop to talk to people. Bookshops, like authors and publishers, play an important role in movements for social change. As such, they are often targets of repression. We must continue to defend and support radical bookshops as part our efforts to build a better world.

[PDF]