Anonymous submission to North Shore Counter-Info

A defense of anarchist subcultures and a proposal for one we could build

I’ve been thinking a lot about subculture the past two years, and had intended that this month (May, 2019) be a deadline for getting out a piece of writing about it. I didn’t do that, because writing gets harder and harder as years go by, because online projects felt more immediate, more urgent, more like a living conversation, because I just didn’t get to it. But since part of what I had wanted to propose was that we have more intentional conversations as an anarchist milieu/community/movement/culture, and that we return somewhat to writing and printing as a means of doing that, it felt wrong to not put something on paper. I would rather this were a finished document with punchy, certain proposals. I suspect I’d get more response if it was. But it’s not. Consider it more of a published draft.

If this reads like critique, which I’m not sure it does, know that I’m critiquing myself as much if not more than anybody else. If I had transcended these problems even a little bit on a personal level, this zine would be finished. Among other things.

*

I hate when anarchists get into their mid thirties and start talking like anarchism is dead, like we are nothing, like the “good old days” have passed and now we’re doing it all wrong. I wish those people would realize that often it’s them who have changed, that the scene is still vibrant and that action is usually still happening somewhere out there. I’m going to remind myself of this once per paragraph as I write this thing. Silently sometimes, but I’m going to repeat it in the text too because it’s really important. We are not dead. I am not dead. I am not old. The kids are alright. History is happening, things are always changing, but if you think that the whole world was at its best when you were 21 and feeling excited about your newly-minted adult life, you are not the only one, and you’re probably not right.

But something is always wrong, we can always do better, pendulums swing in various directions and we fuck up, often in the same ways over and over again. And in trying to correct those fuckups we end up recreating someone else’s fuckup from a generation or so ago. That’s ok because we’re also trying new things all the time – in the streets, in our relationships, in our long-term projects, in our attitudes towards the world. I really, really believe that. Sometimes we get worse, and sometimes we get better. Like all things.

*

The thing that I particularly feel wrong about right now is a bit hard to articulate. When I try to get it out it seems like it’s all already been said, and like I’m trying to synthesize a bunch of things that maybe other people don’t think of as the same problem. But here goes.

When I was a kid, it felt subversive to be political. I had a button when I was sixteen that said “I have an opinion.” Another one that said “Wake up sheep-le (baa).” Apathy seemed like a huge problem to combat, and somehow it seemed like combating apathy would also combat inactivity, like it would be better if people just thought something about the world, how it works, how it doesn’t, how it should. It seemed to me like people’s identities were being reduced by the dystopic march of late capitalism to a set of logos and aesthetic expressions, a Nike check shaved into a head, a mass-produced yellow smiley face keychain, a classroom full of identical Gap sweaters and corduroy pants.

2019, on the other hand, feels very ‘political’ to me. Self-directed expression of political views is a huge part of how we identify and define ourselves online, and an increasing proportion of our self-expression and identity formation happens in digital spaces. People are constantly staging positions, putting them out into the ‘world’ (or at least to the bubble the tech companies have given them to exist within). They write these ideas down themselves, they aren’t mass-produced, branded or identical. They aren’t apolitical or apathetic. They aren’t mindless or devoid of content.

It’s hard to tell how much of this is that I have aged and changed, that youth culture isn’t my culture anymore, but I don’t think that’s all it is. I also recognize that Facebook/Instagram is a corporation, so part of the No Logo critique still holds true, we’re being ruled by these corporations and we are opting into it at every step of the way, making it the means by which we express and construct our identities. Facebook’s relationship to our brand/identity is much harder to see than our corporate rulers of the past, and while both Nike and Facebook give us corporate rule packaged as individual self-expression, the illusion that Facebook sells is much more sophisticated. The individuality that people express through Facebook is not as simple as getting a Facebook tattoo and acting as if it means something unique or special about our self. Instead we perform and mediate our daily lives, express our our true beliefs and values, through a corporate platform. The content comes from within, it feels in many ways as real as the sharpie poetry I used to scrawl on bathroom walls as a way to rage against the machine.

It’s not that we didn’t know about this possibility and reference it in dark comedy of our own all along. The system will co-opt anything it can, and self-expression is a really easy target. They’ll take our ideas and sell them back to us. They’ll give us a nice bullpen in which to have out our fights like the gladiators for social justice that we always wanted to be.

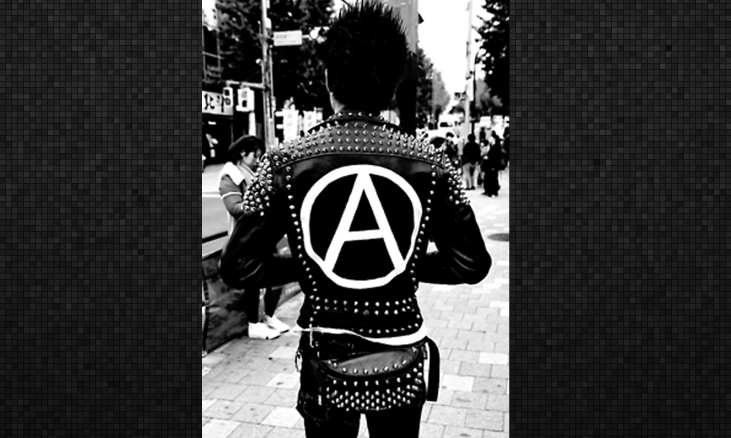

Many real, committed, serious anarchists have embraced the social media version of politics in a way that they never embraced the circled-a hoodies at the mall in 2001. There are a bunch of important and valid reasons for this. Social media has permeated our daily lives to an extent that the brand wars never could. A lot of us had already rejected particular subcultures like punk that gave some of us an opt-out from the Niketown life as exclusionary, ineffective, or escapist. Many social and revolutionary anarchists have chosen social media because they’ve chosen a social life where they engage with regular, non-anarchist people and share their ideas, and they see that those people now do their politics online.

But I want to at least point out that if it was ever subversive to simply express a radical opinion, it certainly is not subversive in 2019. Everybody is doing it. I understand that a lot of us just want to give anarchism a bigger piece of that online opinion pie. I see how it can look like your news feed is just a 2019 version of some public square in the 1890s, where people with radically different positions are clamoring for supporters to build the world they want to build. Maybe some among us would burn that public square and Facebook too, but for the social anarchists who I see mainly participating in this kind of online activity, there should be a fundamental difference. The tech companies and the life they offer us are one of our rulers. They may be a relatively new kid on the block compared to the state and other corporations, but they are one of the biggest forces of domination and control in our world today. Bantering on Twitter as a way to oppose them is way more akin to running for office as a means to oppose the state, or to selling records on EMI to get an anti-capitalist message to a “wider audience” than to demonstrating in a public square or park that happens to also contain buildings and landscaping that were built by capitalists.

When we participate in political discourse on their platforms, we do so on their terms, because identity, communication and diverse opinions are what they trade in. And in this case having radical, controversial, seemingly new or subversive opinions is exactly what they need from us to increase their base of power. This is not the same as the tired bit about the hypocrisy of driving a car powered by fossil fuels to the protest against fossil fuels. Social media doesn’t just want your dollars or your labour, it wants as much of us as it can possibly get. And it doesn’t rely on traditional commodity chains, buy-in is all it has. If people didn’t want it anymore, it would cease to exist, and people would still be fed and clothed to the extent that they ever are under capitalism. There is only the sum of individuals who show their support for the platform by placing more and more of their self and life inside its scope, and expression is exactly what the platform wants, the source of its power and profit. Facebook is much newer than these other industries, so we can see the outside of it more clearly. It also hurts us and our relationships in particularly intimate ways.

But more importantly, I believe that our largely uncritical and unrestrained participation in these spaces is part of a broader buy-in on our part that is hurting our capacity to struggle, not enriching it. We are better, anarchism is better, if we live anarchist lives and show that another way of being is possible, rather than merely participating in the mainstream while arguing for anarchist principles. Social media might make it more possible for anarchism to join “the conversation” alongside a plethora of other ideologies, but it doesn’t make it more desireable. Living anarchist ways of life and forms of struggle visibly and openly is a better recruitment strategy than fitting in, looking and acting pretty much like everyone else, while simply articulating a more correct analysis of power. This has always been true for us, but it’s even more true right now when almost everyone is online shouting an opinion, often a radical or extreme one. If we just argue for and present anarchism, especially if we do it online, without offering something joinable – some kind of movement, community, scene, milieu, whatever term you prefer – we aren’t any better than the rest of today’s armchair warriors. It also helps if that joinable thing is refreshing in some way, if it feels subversive, different from what everybody else is doing.

*

2019 isn’t just extra political, it’s extra connected in general. Just like social media serves us a quantitative increase in political discourse but no increase in true engagement in social struggle, it serves us a huge increase in knowledge of and discussion with our real-life social networks, but no decrease in alienation. Simply knowing more about your friends, where they are, what they think and what they like doesn’t breed deeper or better relationships any more than more people knowing more about a wide range of political ideas breeds stronger, larger, better social movements. It’s been said elsewhere, but it’s worth repeating – we are so, so alienated, and it seems like the deeper into the sea of online “connection” we dive, the more impoverished our IRL relationships become.

Anarchists have spent a lot of time thinking about how we could be more for each other and treat each other better than an alienated, capitalist world expects. We aren’t perfect, and sometimes the allure of the idea of better relationships makes the sense of betrayal that comes with a failed one extra bitter. But many of us have spent lives trying really hard to learn our own ways to connect with each other, to honour our friends and comrades, to build new and better ways of relating to other humans and to the world around us. When we accept the social media life, we risk abandoning that as well, moving more and more of what could have been intangibly beautiful and fruitful face-to-face relations onto platforms that drain them of much of their content and meaning.

A lot of my friends seem to have somewhat given up on living differently together, and resigned themselves to more “normal” lives. They do this for a variety of reasons – pressures from capitalism, falling in love, feeling burnt by relationships past. But in 2019, people, including anarchists, need to find better ways of connecting to each other more than ever. It might feel hard to get back on the “rethinking relationships” horse, but the conversations we’ve been having for years about how to do better despite a context of capitalist alienation might make us better positioned than many others to take on the huge problem that Facebook and the desperate loneliness it creates have brought on.

*

I want us to grow, and to be attractive to people who might join us. To do that, we need to have something to offer. For me, that something wasn’t just a different way of understanding power and the world, it was another way of life. It was a rejection of business as usual, of the “way things work,” in favour of radical community, prefigurative or even lifestylist politics, and a commitment to something other than and in opposition to the daily grind of work and obedience. In my particular case, it was dumpster diving and living cheap in a world that wanted us to work hard and spend big. It was sitting or heckling during the national anthem while others stood blindly. It was being good to each other and emphasizing friendship and community over romance, the couple form, and a future with 1.2 children in the suburbs. It was calling in sick to go to the protest every single time, because the action was more important, because now we had something bigger to live for. It felt dangerous, it felt different, it felt right. It also created a huge gulf between me and the “normal” world, served to alienate me from my family, communities and neighbours to an extent that I now question, and included many practices that I now think do little to further anarchist struggle, but if I hadn’t had some sense of anarchism as a way of life in opposition to the system I hate, I would definitely not have stuck around.

*

Nothing is more emblematic of the 2019 version of control, alienation and domination than social media, and yet anarchists as a whole in my context do very little to differentiate ourselves from it, offer alternatives to the life it proposes, or fight it as an enemy force. Part of this is because it’s hard, because we’re addicted to it, because we’ve swallowed its poison. But another part, a more lucid part, is because of a widespread rejection of subculture and escapism that I think some of us have taken to mean that we should not try to build a different life together at all. To be clear, that rejection happened for a diverse range of valid and important reasons. I do not want to recreate a situation in which folks feel they can not “become” anarchists unless they are young, able-bodied white men who choose to spend their lives train-hopping from summit to summit and eating dumpstered bread. I know that situation pretty well, and it isn’t great. But when I look at anarchism now in my context, it also feels like something is missing. I think that something, that way of life, maybe we should even call it the “subculture,” is a huge part of what we as anarchists have to offer. It should always be changing, growing, rejecting what it has been before and becoming something new. It should also be plural, there should be various ways to exist within it and it should be possible to participate in anarchist activity without fully immersing oneself in anarchist subculture or fully rejecting other important personal ties such as home, family or community of origin. But we should live as anarchistically as we can while fighting for the world we want. We should differentiate ourselves from the system that we oppose so that we will be an attractive alternative to it.

Anarchist subcultures exist. Many of us participate in them. Critiques of “lifestylism” from years ago, the mass exodus among my friends from veganism, dumpster diving, and bicycle culture seems to have drained much of the content from that subculture, but it hasn’t eliminated the social networks. Many of us still socialize mainly with other anarchists, and when non-anarchists enter our social spaces I suspect they still feel that somthing is off or different, that we share cultural norms, inside jokes and reference points, even sometimes aesthetic similarity that they do not share. It seems like in some circles an attempt to reject “lifestyle” has led to an anarchism where we still live different lives from the norm, but we don’t talk as much about what those lives are or why, and those differences don’t have as much political or ideological content as they once did. I think some of us once believed that lifestyle could literally effect change on a broader scale, that if we rode bicycles and rejected cars it would inspire others to also ride bicycles and reject cars, and then so many people would ride bicycles and reject cars that the fossil fuel industry would simply collapse. I now think that line of thinking is absurd, but that culture with its bicycles did draw me to social struggle for a world without (among other things) fossil fuels. I don’t know if the argument that fossil fuels are bad and we should fight the corporations and governments that promote them on its own would have done the same. I think we can still build anarchist ways of life together, which I would call subculture, and that they don’t have to rely on lifestylism, which I define as the belief that individual choices, often consumer choices, can generalize to an extent that they will themselves be practices that change the world. We should continue to recognize that shifting our way of life without attacking power will do nothing to change the dominant culture or the world, but we shouldn’t try to reject subculture, or be normal. We need a cultural context from which to launch our struggles, and that context should have its own norms and ways of life. Those norms should be based on principle, and they should be things that clearly further our participation in important struggles, not detract from them. For those of us who opt into it, that subculture can provide both a social base in which to exist and thrive as individuals and a set of practices and experience that we can invite others to join.

To be clear, I don’t think subculture is the same as community, and in many ways I think subculture is easier to define and understand. Community is a whole other conversation, one that gets us into big questions about who owes what to whom, who counts as an anarchist, and what the quality of our relationships should be. Those are really important questions, and there are lots of texts out there about those questions. I think we should keep having conversations about who we should support and live alongside and how, but here I’m talking more about our choices to be or not be “weird,” “different” or “other” together, even if that together-ness is messy and ill-defined.

I don’t know exactly what this culture should look like, and I mostly want to start a conversation. A conversation about forms of life as anarchists, and about how we might offer a different way of being to those who we hope will join us in revolutionary struggle. I’m now going to offer some characteristics that my version of this subculture might have, but I’m offering them in the spirit of plurality and in hopes that others will join a debate about which of these should be broader cultural norms, which should be relegated to weird sub-groups, and which should be rejected outright as anarchist practice. So here goes.

1. Collective abstinence or near-abstinence from personal social media, and very limited use of social media platforms for promotion, with the explicit intent of drawing people offline while drawing them towards anarchist practice.

The detached, performative political and social identities that we project on facebook are producing and furthering our own alienation, and reducing us to hollow, simplified, symbolic versions of our collective selves. We have to untether ourselves from this, and the thing that we mostly have not seriously tried as a community is abstinence. This will make us seem less human, less present to regular people. They will find it hard to keep in touch with us and sometimes they will forget we exist. We will have to have each other’s backs in person, we will have to build healthy ways to communicate with each other and with people we haven’t met yet, and we will have to build a social force that can not be ignored, despite that barrier. Many of us already have these things and don’t need social media, but feel we can’t get off of it without withdrawing from social life, including withdrawing from the anarchist conversation. We will have to be brave, and we will have to collectively agree to move our conversations elsewhere. It might feel annoying at first, but the relationships we have on social media are so impoverished that I really believe it will be worth it. The more of us do it, the easier and better it will be. We will have to trust ourselves that we know a life without Instagram is a better life, is worth it, so that when someone asks us if they can add/like/whatever us we can proudly say that we don’t do that shit and offer the myriad other ways that we can be reached and found. Some people will not bother to find us that way, but the social media machine is so big and so scary that surely some will also be drawn in by the allure of joining us in a life that rejects that machine.

Not being on social media will differentiate us from the rest of politics and from normal life. Maybe that sounds like a problem, but I think it could be one of our greatest assets if we let it. We will get less likes and clicks, maybe we will even get less real engagement in a numerical sense, at least for a time. But I think that engagement will be more meaningful and lasting. I don’t propose doing this alone, or adopting a holier-than-thou approach that shames individual people, especially non-anarchists, for using social media platforms. I propose that we use the strong, supportive networks we already have as anarchists to make this possible for us, and to invite others to do it with us when they join us in anarchist struggle and community. In places where those networks don’t exist, we must build them.

We know that Facebook, Twitter and Instagram are horrible, for us and for the world, and inviting others to join us in living a life without them will make us a lot more inspiring than any number of politically correct tweets. The rapid and totalizing shift towards lives lived so entirely online is repugnant to a lot of people beyond our social circle, and the prospect of a community or network that relates and communicates in a radically different way from that might draw a lot of people in. That’s not to mention the substantial impacts on our mental health and relationships, and the obvious security concerns that come with continuting to participate in the forums that the social media giants are offering us.

2. A critical relationship with the couple form.

Being an anarchist places a lot of strain on our relationships with home and family, and how we each choose to navigate that with original homes and families is our own. When I made this choice, I felt like there was a lot of love and support, maybe even a new home and family, waiting for me on the other side. I’ve heard a lot of people speak as if they were promised a lot of connection and support in the anarchist milieu, but that promise was not kept for various reasons. I also see that a lot of people end up withdrawing from anarchist life as they age. I think we need to enmesh ourselves in each others lives by truly committing to radical friendship and comradeship so that we can not and do not want to live without each other, and so that our lives will seem to not go on if we withdraw from anarchist struggle. I do not think this would always be incompatible with romantic love, but I do think that coupled romance is the main reason for the breakdown of such relationships in my immediate community. Chosen family is how I plan to keep myself in anarchist struggle and community for the long haul. There are a lot of other ways that this could be accomplished, but I suspect that prioritizing one person and relationship above all others is unlikely to do it. That’s especially true when we consider how volatile romantic relationships tend to be. It also makes us unavailable to provide the kind of deep connection that friends and comrades who haven’t found or don’t want to find their ‘someone’ will certainly need if we want them to stay here with us too. Whenever we talk about circles of affinity, someone brings up the problem of people who don’t have people, who are alone. That will always be an ethical concern if we value free association, but I think it will be less of a widespread problem if we stop uncritically throwing ourselves into one other person at a time and start honouring and nurturing the relationships we have with our friends and comrades.

3. We should support each other economically and practically, building lives in which we are indispensable to each other. However, we should do this face to face, non-hierarchically and through relationships of trust and mutual struggle, not by creating separate classes of “doers” and “funders” as some people are doing on Patreon in the name of mutual aid. We should build our own system in which we can all work less, or ideally not at all. Patreon is the antithesis of this, relying on some people’s “wage work” to fund other people’s “activism.” We should collectively provide the things that we actually need for all of us to keep fighting.

4. A commitment to sharpening both analysis and praxis.

We should create intentional spaces where we debate ideas, change our minds, and find others who want to try out the same practices as we do. I think anarchist gatherings could serve part of this purpose, and in some contexts are close to doing so. We should keep writing, keep talking, keep arguing and start admitting when we have changed course more often. We should try new tactics and analyze new aspects of the world we inhabit. Some of this might still happen on the Internet but it should be about figuring out what to do, not asserting our identities. This means it probably can’t happen on Twitter or Facebook, where every statement is a fashion accessory attached to a personal brand. If we’re going to participate in a subculture, we have to make sure that it’s about something, that it serves to sharpen and build our sense of purpose, not pacify it.

5. Build anarchist rituals and social spaces.

We should have times and places where we get together to assert and revel in our collective existence. These things help us to feel whole and remind us of what we have, like holidays do for some people with their bio families. Some of them also make us findable and visible, and give opportunity for newer people to test out what it might feel like to join our world. In my context I think of May Day, which I spend every year at a demonstration alongside other revolutionaries, thinking of the many people in many different contexts who are doing the same. I also think of New Years Eve, when many of us yell, bang drums and shoot fireworks in front of prisons before having a party with our friends. Neither of these demonstrations serve a particular unified purpose that is accomplished during the action, but they are ours and that always feels important in the moment. I also remember fondly another city and another time where Food Not Bombs servings brought a lot of us together once a week to talk politics, share our positions with others who weren’t already like us, and eat (mediocre) food together. I am done eating undercooked lentils and I don’t believe in “service” per se, but I wonder if I could build something similarly regular, social and open into my daily or weekly anarchist life.

Basically, I think revolutionaries need both intimate friendships and broader cultures and communities. In some contexts, that broader context could be a neighbourhood, a sense of nation or a shared social position. For many anarchists, it’s probably none of those things. Given that, I propose that as we continue to live lives that are shaped by our participation in specifically anarchist struggle for a better, freer world, we build ourselves at least a subculture to do it from, and that we let that subculture look a little weird, but still inviting, to those outside of it. It doesn’t have to look like communities we’ve outgrown or rejected. It doesn’t have to totally alienate us from our neighbours, coworkers and families. But we have to have each others’ backs and build intentional practices together, in ways that mainstream urban North American culture does not encourage, and so we’re going to have to do something different.

email me – subculture at riseup dot net.