From subMedia.tv

Make sure to press CC on the video player for English subtitles

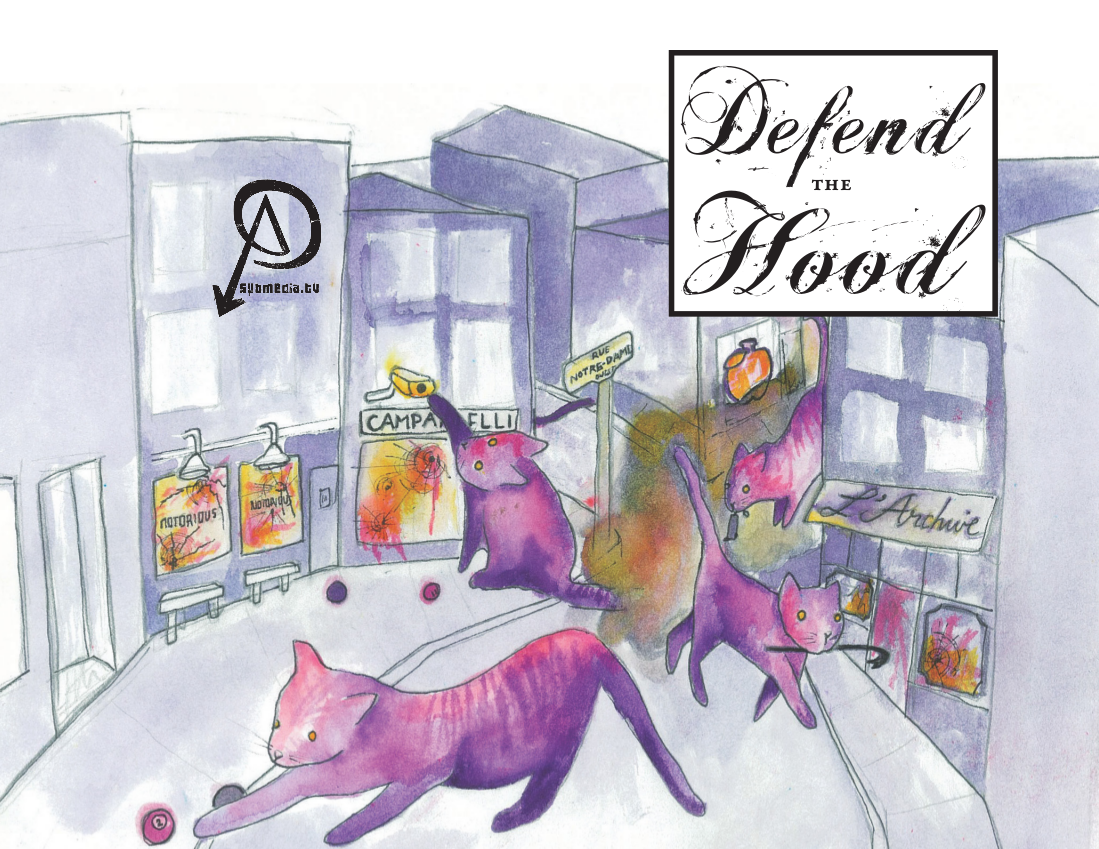

In 2016, numerous attacks were launched at diverse symbols of gentrification in the Montreal neighborhoods of Hochelaga-Maisonneuve and Saint-Henri. We wanted to give space to the people involved so that they can explain a point of view, that corporate media consistently ignore or misrepresent. subMedia has obtained an exclusive interview with two anarchists involved in the actions.

To protect their identities, the voices have been dubbed by actors.

What does it mean for you to fight against gentrification?

1. Before anything else, we’re just talking for the two of us, not for anyone else who participated in the action. We don’t want to represent anything.

2. I don’t want to limit myself to fighting against gentrification, which I see as an intensification of the misery of capitalism. And I’m against capitalism in all its forms. I struggle against gentrification because it effects my life and the lives of many people, but also because it’s a context that allows the exchange of ideas and practices, to nourish a larger perspective of anarchist struggle. I’ve been inspired by anarchists in other cities who have anchored their struggles in where they live. They’ve managed to make certain neighbourhoods dangerous for the authorities and not very welcoming for capitalist businesses. I would like for the police to be afraid of being attacked when they patrol Hochelag, for small yuppie businesses to hesitate before setting up shop here because their insurance premiums will be super expensive, for people to think about how if they park their luxury cars in the neighbourhood overnight, they’re risking waking up to them being trashed, that as soon as graffiti or posters are cleaned, they’re back up.

1. And if we want these people to be afraid, it’s because we want the space to experiment with other ways of living, and cohabitation with them isn’t possible. Their world will always want the destruction of other worlds, those of freedom, of sharing and gifting, of relations outside of work and leisure, of the joy outside of consumption…

2. I think it’s worth being explicit about how the struggle against gentrification is inevitably a struggle against the police. The main tool that the city has to move forward with its project of social cleansing is the police and the pacification of residents. This reality is at the heart of the reflections that orient our actions. The pacification takes different forms: it’s the installation of cameras, the management of parks and streets, but also it’s the imaginary created by bullshit narratives like “social mixity”. The public consultations, the studies and projects of affordable housing are all just a facade: during this time, the social cleansing advances and more and more people are evicted. If these means of pacification don’t work, the city has recourse to repression, that’s to say, the police. It’s the police who evict tenants, prevent the existence of squats, etc. Every form of offensive organization that refuses the mediation attempts of the municipal authority will one day be faced with the police. So it’s also important to develop our capacity to defend initiatives against repression.

Without necessarily throwing aside community organizing, many anarchists prefer the method of direct action. Why?

1. We don’t have demands. We didn’t do this action to put pressure on power, so that they grant us certain things. For sure people should have access to housing, but I don’t think that we should wait for the State to respond to the demands for social housing that have existed since the 80s, in a neighbourhood undergoing gentrification. I’m more interested in seeing what it would look like for people to take space and defend it, without asking. I’m not interested in dialoguing with power.

2. Dialogue with the municipal authorities is, along with the threat of police repression, the principal method of pacification. To keep us in inaction, imprisoned in an imaginary where we can’t take anything or stop anything from happening.

1. What’s special about direct action is that you finally do away with the ultimate mediator, the State, by acting directly on the situation. Rather than giving agency to the city, in demanding something of it, we want to act for ourselves against the forces that gentrify the neighbourhood. The State is afraid of people refusing its role as the mediator.

Why choose a strategy of direct action outside of a context like those created during social movements?

2. Because we don’t want to wait for the ‘right context’. We think that it’s through intervening in fucked up situations in the world that we live in that we create contexts. The fact that this world is horrible is in itself a ‘good context’. Revolt is always worthwhile, every day.

1. I think that’s important to emphasize, I don’t believe in waiting for social movements to act. Acts of revolt have many impacts, even if they’re not inscribed in a social movement. And also, when the next moment of widespread revolt comes, we’ll be better prepared to participate.

Lastly, what do you say to those who say that gentrification is an inevitable process?

1. Gentrification is a process of capitalism and colonialism, among others. It makes itself seem inevitable, and maybe it is, but it’s nonetheless worthwhile to struggle against it and to not let ourselves be passive. In a world as unlivable as the one we’re in, I have the feeling that my life can only find meaning if I fight back.

2. At best, the process of gentrification will move elsewhere, if a neighbourhood resists. And yet, struggling against capitalism and the State opens up possibilities that otherwise wouldn’t have existed.