Anonymous submission to MTL Counter-info

In response to the media’s attitude towards the demonstration of Friday, November 22, 2024 in Montreal

If we are writing these lines today, it is because for several days, the media have been endlessly focusing on broken windows and spilled paint following last Friday’s anti-NATO demonstration. This obsession with the destruction of material goods, however, obscures a much more fundamental question: why is anger exploding in this way?

Where the media focuses on inanimate objects, they neglect a much more complex emotional response: this violence is not gratuitous. It symbolizes a cry of helplessness in the face of destroyed human lives, erased memories, and persistent pain that, far from being heard, is reduced to statistics or isolated facts. The debate should not be limited to broken windows, but should ask what motivates this desperate gesture: a distress, a cry of revolt in the face of insidious and omnipresent violence.

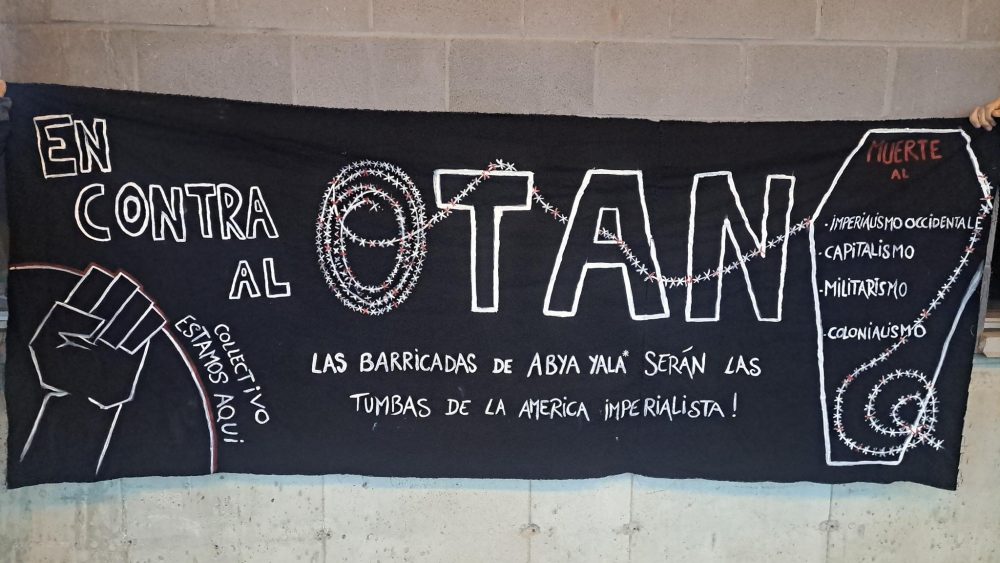

We, members of the Colectivo Estamos Aquí, went to this demonstration to express a legitimate anger: that of the survivors of a military dictatorship in Guatemala, which caused more than 250,000 deaths, 45,000 disappearances, and destroyed hundreds of Indigenous communities. This is the memory that we came to defend. A memory that the authorities of the Americas and Europe seem to want to relegate to the background, under the pretext of political and international issues that are too complex for the populace. But what about the integrity of the colonized, displaced, and killed people? Their emotions and traumas, their own issues? This violence, that of the oppressed, seems to have been normalized, even forgotten.

Anticolonial struggles, whether in Latin America or elsewhere, are all linked by common roots: exploitation, domination, and dehumanization. These struggles, despite the diversity of their forms and contexts, all attack a global system of injustice and repression.

However, the media prefer to divert attention from the root causes and focus on the material damage. In doing so, they minimize the violence of a system that destroys human lives in favor of commodities. It is as if, somewhere, the roles have been reversed and that it is now objects—and not human beings—that embody the soul of the world.

In this hierarchy of values, where possessions are elevated to the highest rank, human beings are gradually reduced to simple functions: those of producers, consumers, tools of capitalism. The real violence here is not the breaking of windows, but the systematic disregard for human lives.

Everywhere, Indigenous peoples are reduced to exotic symbols or exploitable resources. Their lands are plundered, their cultures marginalized, and their voices stifled. This dehumanizing treatment reflects a persistent colonial vision, where the dignity of human beings is denied to justify the exploitation of resources.

We are told that violence has no place. Yet, faced with institutional violence of monstrous force and magnitude, the question deserves to be asked: is violence not sometimes the only possible response?